Reincarnation has become an increasingly popular doctrine in the West. For example, polls taken in the US over the past couple of decades have shown that between 20 and 28 percent of the population believe in it. The figures for western Europe are similar.

What explains the appeal of an idea that until recently was the province of a few occultists and eccentrics? Some of it can be explained by the appeal of Asian religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, to which reincarnation has always been integral. But this does not explain much: you could turn the argument around and say that Hinduism and Buddhism are so appealing because they teach reincarnation.

The allure of the doctrine is easy to see, particularly when it is weighed against the conventional Christian view of heaven and hell. The latter is hard to defend in the light of any real sense of cosmic justice. It holds that the deeds of an individual’s life on earth will bring upon him either eternal reward or eternal damnation. And this is hard to swallow. Even the greatest monsters of history, no matter how many evil acts they committed, committed only a finite number of acts. How can even these extreme cases merit an infinite series of punishments?

By contrast, the doctrine of reincarnation, along with the closely associated doctrine of karma, holds that evil acts do entail retribution – but only in proportion to the act. The punishment suits the crime. Nor do good deeds done in a single life win the individual an infinite life of bliss, merely a limited number of auspicious future lives.

The idea of reincarnation has also spread because of the specific form in which it has been disseminated. Many of the ideas about reincarnation in New Age and other sectors of alternative spirituality can be traced back to the influence of Theosophy. During the 136 years of its history, the Theosophical Society, always a tiny organisation (worldwide membership in 2008 was under 21,000), has been influential out of all proportion to its numbers.

The Theosophical view of reincarnation is fundamentally an optimistic one. There is a purpose to these nearly endless cycles of birth and death. It is the education of consciousness. The Self descends into the darkness of materiality through a process known as involution. Then it begins to reascend, through a process known as evolution. This is not the evolution of the Darwinists, which is essentially a blind and meaningless process. Rather it is a carefully structured series of lessons in identifying with, and then detaching oneself, from the material world. Each separate incarnation is a tiny phase of this process.

Thus the trajectory of the journey of each human soul is an upward one. An evil or misspent life is only a delay or setback in a process that is ultimately going in a positive direction in any event.

When it’s stated this way, one immediately sees why this idea is so appealing. Far more than the conventional Christian view – or the secular materialist view, which holds that death is final and nothing survives the body’s demise – the evolutionary picture of reincarnation speaks to the current age, with its deeply rooted belief in progress.

This view of reincarnation, pioneered by the Theosophists, differs in some major ways from the pictures given by Hinduism and Buddhism. These portray the soul’s progress not as an ascent upward, where success is ultimately guaranteed no matter how many setbacks take place along the way, but as a merciless whirligig from which the only recourse is to escape. Indeed, they teach that we have lived through this cycle a virtually endless number of times already. In the Hindu Katha Upanishad, Death says:

The passing-on [i.e., death] is not clear to him who is childish,

Heedless, deluded with the delusion of wealth,

Thinking “This is the world! There is no other!” –

Again and again he comes under my control.

And in one of the Buddha’s discourses we read, “What, monks, do you think is more: the water in the Four Great Oceans or the tears, which you have shed when roving, wandering, lamenting and weeping while on this long way, because you received what you hated and did not receive what you loved?”

The fundamental cause of this cycle of rebirths, in both Hinduism and Buddhism, is ignorance or heedlessness. The remedy is enlightenment, which (in Hindu terms) leads to moksha or release, or (in Buddhist terms) to nirvana, or cessation. For the rest of this article, let us focus specifically on Buddhism.

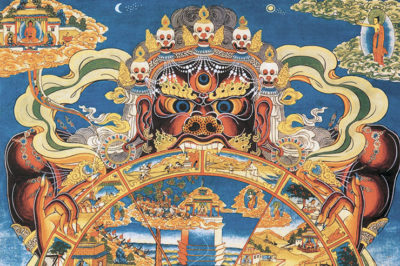

One of the most elaborate pictures of the cycle of births and deaths can be found in the Tibetan Buddhist Wheel of Birth and Death. While the symbolism of this wheel is too intricate to describe in full here, one thing it depicts is the six realms of existence, three of which are bad, three of which are comparatively good. The three good realms are those of the gods, the asuras or demigods, and humans. The three bad realms are hell, the realm of the pretas or hungry ghosts, and the realm of animals.

Beings are drawn to the hell realms through acts of violence and cruelty. As in Christian teaching, these are places of unimaginable suffering. The thirteenth-century Tibetan sage Longchenpa writes:

All the tears you have shed would be more (than the water) in the four oceans,

And the amount of molten metal, foul blood, and excrements

You have consumed when your mind had become a denizen of hell or a spirit [i.e., a preta]

Would not be matched by the rivers flowing to the end of the world.

Longchenpa again emphasises the circularity of this process: his description of hell is not a warning of future punishment, but a reminder to the aspirant of what he has already undergone during many lifetimes in the immeasurable past. Buddhist teaching differs from that of Christianity by saying that since karma is finite, the suffering of hell beings and pretas, though enormous, is finite as well.

The animal realm is less painful than the worlds of the hell beings and hungry ghosts but scarcely more desirable. Humans are drawn there by bestial behaviour – by obsession with food or sex, the cravings that we share with the animals. While animals do not suffer continually, they too are beset with pain and grief. Moreover, they do not have the mental capacity to achieve liberation, “not realising the natural misery of their state,” as Longchenpa puts it.

The human realm, although it too is characterised by suffering, is the most auspicious. Buddhist texts emphasise the rarity and preciousness of a human birth. The sage Nagarjuna writes:

More difficult is it to rise

from birth as animal to man,

Than for the turtle blind to see

the yoke upon the ocean drift;

Therefore, do you being a man

practice Dhamma [the Buddhist teaching] and gain its fruits.

Here lies the advantage of being born into the human realm. Individuals here are not so deeply immersed in suffering as they are in the realms of hell beings and hungry ghosts. Nor are they in such favourable circumstances as the gods, who enjoy so much pleasure and delight that they have no interest in liberation, or even the demigods, who have relatively enjoyable circumstances but are tormented by the jealousy of the gods, with whom they wage continual warfare. The human existence is an intermediate one, where beings are endowed with enough intelligence to follow the path to liberation but not so intoxicated with pleasure that they have no interest in it.

Note that the gods and demigods, though their lives are pleasant compared to ours, are not immortal. Eventually their good karma is exhausted and they fall down into less favourable realms. This goes on endlessly. In one traditional text, a sage who is asked about the power and strength of Indra, king of the gods, points to a line of ants marching on the ground and says, “Each of those ants has been an Indra.”

It would be mistaken, however, to conclude from all this that Buddhism is at its core a pessimistic, world-denying doctrine, as many have done. The German scholar of Buddhism Hans Wolfgang Schumann observes, “To assume that in their present life more than a few advanced seekers are able to conquer craving and ignorance would be to overrate man. Most men will need a long time, a whole series of rebirths in which by good deeds they gradually work themselves upward to better forms of existence. Finally, however, everyone will obtain an embodiment of such great ethical possibilities that he can destroy craving and ignorance in himself and escape the compulsion for further rebirth. It is regarded as certain that all who strive for emancipation will gain it sometime or other.”

Schumann is referring to the attitude of the Theravada (“way of the elders”), one of the two primary divisions of Buddhism. The other sector, known as the Mahayana (or “great vehicle”), which includes such lines as Tibetan Buddhism and Zen, moves still further in a universalistic direction. It encourages its adherents to strive, not for nirvana per se, but for the condition of the bodhisattva – one who renounces or rather postpones enlightenment to work on behalf of the illumination of all sentient beings. In short, both sectors of the Buddhist tradition are ultimately positive in nature. If they do not teach evolution as such, they nevertheless hold that the gates of mercy are infinite and will eventually accommodate all beings, no matter how far they may seem from their goal.

SOURCES

Robert Ernest Hume, ed. and trans., The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, 2d ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931.

Klaus K. Klostermaier, A Survey of Hinduism, 3d ed., Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2007.

Longchenpa, Kindly Bent to Ease Us, Part One: Mind, Translated by Herbert V. Guenther, Berkeley, California: Dharma Publishing, 1975.

Hans Wolfgang Schumann, Buddhism: An Outline of Its Teaching and Schools, Translated by Georg Feuerstein, Wheaton, Illinois: Quest, 1974.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.