From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 14 No 5 (Oct 2020)

When something dramatic happens, we want an explanation. We want answers to questions like: Why is it happening? Who is responsible? Where is it heading? What does it all mean?

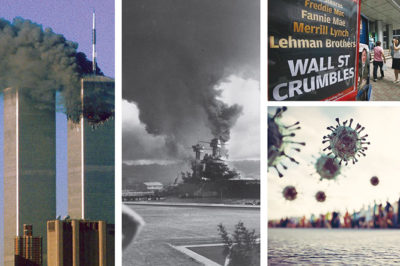

In the mainstream narrative – the approved orthodox version of events – a clear meaning is always provided, often alongside the news of the dramatic event itself. On the morning of 11 September 2001, even as the events were broadcast of the twin tower explosions, a banner streamed across TV screens: America under attack by Al Qaeda. And: They want to destroy our democracy.

This prompt designation of meaning to an event has an important psychological effect. The first plausible explanation someone hears for a dramatic or traumatic event tends to fix in the subconscious and resists displacement by later explanations. That’s why the orthodox mainstream meaning is quickly delivered, repeated endlessly, and reinforced from a variety of angles by various mass media genres – news broadcasts, newspapers, talk shows, interviews, official announcements, comedians, sitcoms, documentaries, etc.

It is easy to see why followers of mainstream media consider themselves well informed. On any public topic, they know the meaning, and from that framework they discuss this or that development with a sense of knowing what it’s all about. For every story, big and small, the media always gives us a why along with the what.

The Closed Orthodox Bubble

The world of the mainstream narrative is, to a large extent, a closed bubble of meanings and beliefs. Its stories and the attached meanings cover the whole scope of ‘what’s important’, and there’s little room for alternative explanations. Contrary explanations from non-mainstream sources are easily dismissed: We already know why that happened. And: Who are you that thinks you know better than the world’s experts? Every explanation that comes from outside the bubble is automatically suspect.

Because it explains everything, the mainstream narrative naturally defends itself against info-intrusions into its bubble. That is to say, media faithfuls tend to quickly dismiss such intrusions. As if that weren’t enough to keep the bubble sealed, there are specific mechanisms – what we might call info-firewalls – that are ever-present in the orthodox world.

For many years now, ever since the JFK assassination, we’ve had the ‘conspiracy theory’ firewall. Any contrary meaning or narrative of events is tagged right away as ‘conspiracy theory’. And conspiracy theorists, as we all have been told in the mainstream world, are a bit unbalanced, have authority issues, tend to be paranoid, need to get a life, etc. Not a place to go for useful information.

More recently, growing out of events involving Wikileaks and the 2016 US presidential election, we now have a ‘fake news’ firewall. In the middle of the election campaign, Wikileaks released information that should have seen the Clintons and their foundation indicted for serious crimes. This obviously wasn’t going to happen in the real world of Washington politics, and a quick info-fix was needed. Instead of responding to or denying the leaks, they were simply branded with a fresh new term – ‘fake news’ – a term that soon became an all-pervasive meme, automatically applicable to anything that contradicts the orthodox narrative.

The orthodox bubble is sealed tight with strong defences against contrary ideas, reinforced by firewall memes. This is why it’s impossible to discuss issues with an orthodox believer if you have a contrary understanding of the meaning behind the events of the day. They don’t want to hear what you have to say because they know it’s either ‘fake news’ or ‘conspiracy theory’. Your attempt at info-intrusion can even be received as an insult, suggesting that the person isn’t well informed and in need of coaching from ‘arrogant you’.

Orthodoxy & History Without Meaning

In the orthodox world, big changes always come as a response to an unexpected crisis (e.g. Pearl Harbor, 9/11, the 2008 GFC, COVID-19). A crisis is identified, given meaning, and changes announced. Another crisis comes along, and again we get big changes. Each crisis comes with its own little meaning story, unrelated to the meaning of the crisis that came before or the one that comes after. Society stumbles along, it seems, always responding to unexpected crises.

Each transformation society goes through is given a definite meaning, but no meaning is assigned to the sequence of transformations. There is no path being followed; we are not heading in any direction; there is no meaning in the combined effect of all the changes we’ve gone through. There can be no meaning in society’s trajectory, in the orthodox world, because in that world we know very well that the trajectory has been imposed on us by unexpected random crises. Any suggestion of some kind of direction or path can only be a paranoid fantasy – you are seeing patterns where none exist, like a Rorschach inkblot.

That’s what we face when discussing anything with orthodox media faithfuls: a sealed-tight limited understanding of the world, including a perspective that sees historical change as a sequence of random events.

Fort Orthodox & Implanting of Meaning

Fort Orthodox is a solid edifice, and the psyop (psychological operations) mortar binding it all together is control over meaning. That’s why a meaning is declared right away – even if it’s a mystery how they figured things out so quickly. The meaning is repeated endlessly, via multiple info-genres, and kept alive thereafter. No one ever refers back to the events of 9/11 without including mentioning that horrible terrorist attack.

Declaring a meaning is much easier than trying to prove the truth of that meaning with data and arguments. If every voice in the media repeats with confidence the same meaning, it quickly sinks into the listener that it is something “everyone knows to be true.” Of course, there will also be testimony and evidence presented, but this need not go beyond the cursory. Since people already ‘know’ the meaning, the who & why, they need very little in the way of evidence to feel that the meaning has been adequately verified. Psychologists call this confirmation bias.

Arguments over evidence have little impact on Fort Orthodox. An articulate orthodox faithful might respond to contrary evidence this way: “Not only has your evidence been debunked, by trusted fact-checkers, but the official story was proven – wasn’t there the 9/11 Commission and some article in Popular Mechanics? I didn’t bother with the technical details myself, no need. The experts are dealing with all that, and I don’t want to talk about it with you.”

Thus, the whole power of Fort Orthodox stands on one tactic: prompt implantation of a declared meaning deep into the psyche of the listener, followed by ongoing comprehensive reinforcement. This powerful tactic makes the job of info-propaganda much easier as the believer only looks for verification, rationalisations, but not proof. With meaning firmly and promptly established, the media can focus right away on promoting the subsequent actions required following their declaration of what it’s all about, e.g. terrorist attack, Novichok poisoning, deadly pandemic, etc.

Open-Source World of the Real

Whereas Fort Orthodox is a closed bubble of information and meaning, existing outside that bubble is a wider world of open-source information and meaning available from alternative publications and the internet, with a wide variety of explanations.

In order to be considered a well-informed citizen in the orthodox world, you need only turn on the TV or open your newspaper and absorb. To become a well-informed citizen of the real world, making use of what’s available open-source, is a much more challenging undertaking. You must rely on your own judgment, discriminate between the wheat and chaff, and make overall sense of what you learn.

I’ve been doing my best to be a well-informed citizen of the real world, using open sources, for many years now. I’ve found this process to be a journey, never reaching any final ‘land of truth’, but each step on the journey peels away one more layer from the onion of meaning. Not only are there deeper meanings for specific events than those offered in the orthodox world, there are also meanings that tie events together, that reveal directions and paths in society’s trajectory.

Real Meaning of Crisis Events

The declared and implanted meanings found in the orthodox world are among the earliest layers of the onion to be peeled away. Those meanings don’t need to stand up to scrutiny as their means of implantation is based on psychological processes and repetition, not on hard evidence. For example, considering the events of 11 September 2001, if you look closely into the evidence, it becomes apparent that the orthodox meaning – terrorist attack – makes no sense. We have a mountain of evidence in the non-orthodox world.

There is a standard pattern in the crisis-response scenario. First, a crisis event is declared along with a declared meaning. Then the media reveals steps to be taken in response. This always involves the expansion of government activity into new areas with new initiatives and new powers. The real meaning of each crisis scenario, it turns out, is always the same:

Who defined the crisis and its orthodox meaning? Those who fashion the narrative. Why did they choose that meaning? For the government to claim the right to specific new powers. Where will this lead? To the exercise of those new powers.

The crisis event itself is more or less irrelevant to the scenario. The event might be imaginary, invented or engineered (for example, babies cruelly removed from incubators – the Gulf War in 1990, Weapons of Mass Destruction – the Iraq War in 2003, or the Gulf of Tonkin false flag in 1964 – the Vietnam war). The real meaning of a crisis is always the ‘response’.

Cross-Bubble Conversations, A Best-Practice Approach

We have a real world, with real meanings behind events, and an orthodox world, a matrix world, with its illusions maintained by implanted meanings. Implanted meanings are resistant to outside influence, as we have seen, but they are at the same time quite fragile if evidence becomes relevant to the conversation.

Conversations – about evidence or about the meaning of events – are nearly impossible across the boundary of the orthodox bubble. Each side sees itself as being well-informed, and the other misinformed. Neither sees the other’s viewpoint as worthy of serious consideration. Both parties in such an exchange feel that their knowledge is not respected, and their attempts to point out obvious facts are dismissed out of hand. Such conversations, if attempted at all, soon sputter to a stop, succumbing to frustration and annoyance.

In such a conversation, if they can be called conversations, each person feels they have the real facts. But the other side isn’t really listening because they have their own real facts that are more relevant. What each wants from the other is to be heard, for their viewpoint to be given a hearing.

If those inside the bubble won’t give your ideas a hearing, triggered as they are by the barrier memes, it is up to you to take the first step, to introduce listening into the conversation.

The confrontational approach, pushing ideas and facts at the other party, does not work. When challenged, people tend to grasp and hold more firmly to familiar beliefs and truths. We would do better by seeking to understand where they’re coming from and how they see the world. Start by asking questions instead of making claims. If you give their ideas a hearing, it is likely they’ll be willing to hear something about where you’re coming from and how you see the world.

We need to recognise that it is quite understandable that an intelligent, critically thinking person can believe they are well-informed in the mainstream world. They get packaged explanations for everything, and they hear the same message from many authoritative voices. Why should they doubt what ‘everyone knows’ to be true? We need to respect that such a person is doing their sincere best to be a well-informed citizen, and we need to include politeness in how we talk to people.

If you want to get to a place where you might be able to talk about controversial issues, you need to begin by leaving controversy out of the conversation altogether. Instead, the focus needs to be on developing rapport, showing respect for what the other person has to say, and building trust by not being judgmental. This is a process, an investment in relationship building. And the investment is necessary if the conversation is ever to reach more challenging territory – without triggering defensiveness.

Undermining Fort Orthodox

As long as the orthodox narrative monopolises a critical mass of public opinion, society will be easily led down the garden path to a technocratic dystopia, each step disguised as a necessary response to a dangerous crisis. We are already far down that path.

Opening a mind to the possibility that all may not be what it seems is the secret. Perhaps this doubt will be shared with fellow orthodox faithfuls. Perhaps a spark of curiosity is raised, and our doubter starts looking around on their own, expanding their info-sources.

Many of us already try to wake people up from the all-pervasive narrative. On the internet, people post revelatory articles and jump on comment threads, sometimes risking controversy in conversation. Fort Orthodox remains unshaken by these confrontational approaches. It doesn’t make sense for us to keep doing the same things and expect anything different to happen.

If we invest that same energy in pursuing respect-based conversations, we are more likely to succeed in opening minds to non-orthodox perspectives and meanings.

Another internet example: Instead of sharing controversial articles or news, to be read mostly by people already on your side, you might comment on an orthodox friend’s posting, acknowledging their point, and asking to hear more about that perspective. If a conversation develops, you might move to video chat. When you can see one another, the conversational process will proceed more efficiently and on a deeper level.

Fort Orthodox is strong but vulnerable. Its strength, its implanted meanings, are also its weakness. Those meanings often don’t stand up to scrutiny when examined by an open mind. Each time someone rejects an orthodox meaning that is a micro-quake inside the Fort. If enough of us get enough points across, we generate bigger quakes – and resonance, like what happened to the walls of Jericho.

I invite you to give it a try – experiment in whatever way works best for you and see if you can get a conversation going where before there was a pointless confrontation. Don’t expect anything at first, just practice a new way of engaging.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.