From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 17 No 6 (Dec 2023)

I recall many years ago looking through an old Catholic missal. It was one from the halcyon days of the Tridentine Mass and contained a variety of colour plates designed to help the faithful believer better understand the Mass and the sacraments.

Of the more memorable images from that book was a colour plate illustrating the meaning and origin of the seven sacraments of the Roman Catholic Church. It was a collage of images depicting Jesus Christ administering each sacrament: Jesus baptising someone, Jesus hearing confessions, Jesus confirming a young boy and girl, that sort of thing.

Now, I am sure the authors of that missal did not actually believe that Jesus of Nazareth really did those things, but I am certain that millions of faithful Catholics probably did believe it. And they believed Jesus directly instituted each of the seven sacraments because of what they saw in that missal and because of what their Church taught them.1

One of the problems inherent within traditional Christian orthodoxy is a kind of myopia.

Those with the ocular medical condition known as myopia typically can see nearby objects clearly but distant objects appear blurred.

In terms of Christianity, as illustrated from the missal story above, there is a tendency to think that what a person believes now as “true Christianity” is precisely what Jesus taught, what the apostles taught, and what every faithful and true Christian has ever believed.

This way of thinking blurs the vision when it attempts to look down the corridors of time, back to the distant past and into cultures very different from those of modern times.

Christianity has never been “one thing” or “one true set of doctrines,” as much as some may wish to comfort themselves with such beliefs.

Even in modern times and among the strictest of traditionalist Christian denominations, there are varieties of theological and doctrinal positions, even if those positions are made to look less diverse by institutional unity, as with Roman Catholicism, or by a kind of cultural unity, as with Protestant fundamentalism.

From the earliest days of Christianity, diversity, not uniformity, characterised the movement.2 So, for example, there never was, and is not today, one “official” view of such matters as prophecy, the “end times.”

But not everyone understands or believes this and so, for example, there are many evangelical and fundamentalist Christians who cannot conceive of anyone being a Christian and not believing in the “rapture” or end-of-the-world scenarios of the Left Behind book series.

Someone wisely observed that ideas have consequences. The consequences of ideas are especially evident in the field of religion.

If supporting evidence for such a claim is required, one need only consider how the world today has been affected by the religious ideals of solitary individuals such as Moses, Jesus, or Muhammad.

Religious ideals and the movements they inspire do not have to be pervasive or widespread to have far-reaching consequences.

This is nowhere more obvious than in the strange beliefs of a relatively small sect of Christians who teach a form of Protestant Christianity generally known as “dispensationalism.”3

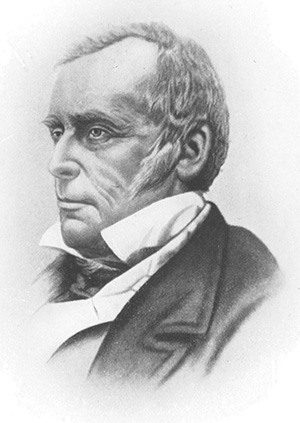

Originating from the work of John Nelson Darby, an Anglican clergyman of the 19th century, and systematised by American followers such as C.I. Scofield, dispensationalism had a tremendous influence on English-speaking Protestant Christianity.4

Dispensationalism is best known for its literalist interpretation of highly symbolic verses of the Bible, its emphasis on the immediacy of the second coming of Christ, the distinction it makes between ethnic Israel and the largely Gentile church, and its belief that God’s ultimate goal of history is the restoration of the Jews as a kingdom nation ruling the world from Jerusalem.

In the way they interpret the Bible, God has divided human history into seven ages or dispensations, and we now find ourselves on the verge of entering into the last age, an age that will, according to them, witness the literal physical return of Jesus to the Earth.

Indeed, in their theological system, Jesus Christ cannot return until the Jews are gathered in their ancestral homeland.

And so, according to them, the founding of the modern state of Israel in 1948 was part of a larger, prophetic plan revealed in the Bible.

All of this would be nothing more than an adventure in religious doctrinal trivia were it not for the fact that the dispensational worldview has, like all ideas, consequences for the rest of us.

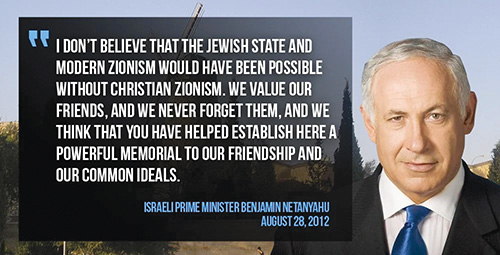

There is perhaps no better example of this than the United States’ constant support for the state of Israel.

To be sure, no US president has been an open believer in dispensational Christianity, but many of them have recognised that a large bloc of voters are such believers and have therefore patterned US foreign policy to cater to that bloc.

Leaving aside the improprieties of US foreign policy, the fact is dispensationalism is bad theology. This can be seen in both its history of fear-mongering and end-of-the-world predictions and in the way it misreads the Bible.

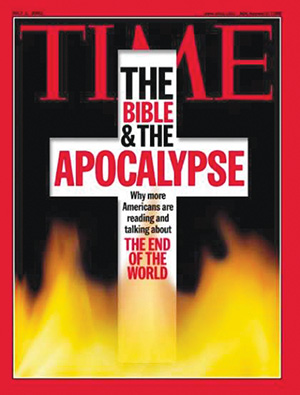

On 1 July 2003, TIME magazine’s cover story was “The Bible and the Apocalypse: Why more Americans are reading about the end of the world.”

Back in the early 1970s, dispensational prophecy author Hal Lindsey predicted the second coming of Christ would occur in 1988 since that was forty years (in biblical chronology, forty years equals a generation) from the time the modern state of Israel came into existence.

Hal Lindsey was wrong, but that has not stopped him from writing many more prophecy books, and it has not stopped Christians and non-Christians from reading them.

From 1998-99, dispensationalists poured over their Bibles for evidence of the “rapture” and the end of all things as the year 2000 dawned. Many books, tapes, and videos were written, produced, recorded, and bought by millions of people, many of whom were convinced the end was at hand.

But, as with the year 1988, so too with the year 2000, the dispensationalists were wrong again.

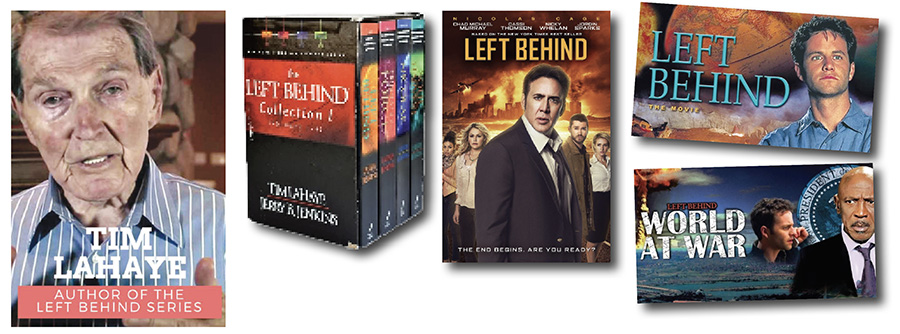

The events of 11 September 2001 again saw people wondering about the end of all things, and Tim LaHaye’s popular Left Behind book series (the first volume of which was originally published in 1995) profited immensely from both the Y2K hysteria and a year later, from the events of 9-11.

Indeed, the Left Behind book series has sold over 40 million copies. That doesn’t include the motion picture adaptation of the Left Behind novel or the many other spin-offs, such as “Left Behind for Kids,” the “Left Behind” board game, music, movies, etc.

Fear-mongering about the end of the world and the return of Christ have made millions of dollars for men like LaHaye, Lindsey, and John Hagee.5 These men quote many, many Bible verses to support their claims. Quoting Bible verses does not, however, make something a true biblical doctrine.

Historically, large numbers of Christians have believed that all of the events dispensationalists have pointed to as evidence we are “closer than ever” to the end times were events that the Bible itself says were to take place in the generation of the apostles and the First Century church. For most of the history of Christianity, such prophetic statements were looked upon as either being fulfilled in the past or applying not to a restored Israeli state but to the church.

Consider these passages and notice that in every case, the words and predictions are addressed not to people living in the 21st century but exclusively to the people to whom Jesus was speaking at the time, the people of that generation, and notice that for them, these things were near, at hand, soon to come (note: I have used italics to emphasise this in the text):

Matthew 10:23: When they persecute you in one town, flee to the next, for truly, I say to you, you will not have gone through all the towns of Israel before the Son of Man comes (ESV).6

Matthew 16:27-28: ‘For, the Son of Man is about to come in the glory of his Father, with his messengers, and then he will reward each, according to his work. Verily I say to you, there are certain of those standing here who shall not taste of death till they may see the Son of Man coming in his reign.’(Young’s Literal Translation of the Bible)

Matthew 26:63-64: But Jesus remained silent. And the high priest said to him, “I adjure you by the living God, tell us if you are the Christ, the Son of God.” Jesus said to him, “You have said so. But I tell you, from now on you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming on the clouds of heaven.”(ESV)

Matthew 24:34: Truly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place.(ESV)

James 5:7-8: Now be patient, brothers, until the Lord’s coming. Think of a farmer: how patiently he waits for the precious fruit of the ground until it has had the autumn rains and the spring rains! You too must be patient; do not lose heart, because the Lord’s coming will be soon. (New Jerusalem Bible)

1 John 2:18: Children, it is the last hour, and as you have heard that antichrist is coming, so now many antichrists have come. Therefore we know that it is the last hour. (ESV)

Notice the verb tenses, notice the immediacy and the urgency in these exhortations, and notice, most importantly, that they were addressed to specific people at a specific time and place!

For Christians who believe in the infallible truth of the Bible, logically, there are only two possibilities for correctly understanding these statements.

Either Jesus was right, and all the things that the dispensational/Christian Zionists claim are to happen in our immediate future have, in fact, already happened, or Jesus, as he speaks from the pages of the New Testament, was wrong!

So, then, “all the things” that the dispensationalists claim are to happen in the future have been misunderstood and misinterpreted by them.

They have managed to find everything from helicopters and atomic bombs to computer chips lurking below the surface of the words of Scripture, but the one thing they seem not to be able to find is the ability to interpret things like “coming on the clouds,” “the moon not giving its light,” and “wars and rumours of wars” in light of what the Bible itself says about those things.

The biblical evidence and especially the time indicators associated with these prophetic statements all show that both Jesus and the authors of the New Testament were all expecting the “Last Days” and the “coming of the Lord” to occur in their generation.

Reading the Bible in its cultural and historical context will show that such concepts, themes and ideas as “the Day of the Lord,” the “Last Days,” and the “coming of the Lord” are usually not associated at all with what has come to be known in our time as “the end of the world and the return of the Lord” but rather with the covenantal judgment of God against the nation of Israel.

According to this traditional Christian interpretation of the Bible, that judgment did occur in CE 70 with the fall of Jerusalem at the hands of the Roman armies of Titus and Vespasian.7

From this Christian perspective, the “last days” were the last days of the Old Covenant era with its Temple sacrifices in the city of Jerusalem and with its High Priests and Scribes.

According to this view, the covenantal judgment of God against Israel was manifest in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple. Hence, it was to the Jewish mind of that time “the end of all things,” and it was, as Jesus himself said in Luke 21:23, “…the days of vengeance, that all things which are written may be fulfilled.”

Vengeance? Vengeance against who?

According to those Christians who argue for the past fulfilment of these prophecies, it was against Israel for rejecting the Messiah and for saying that they had no King but Caesar and for saying that they would not have “this man [Jesus] to rule over us!”

According to the Gospel accounts, Jesus claimed in CE 30 that within a generation all of those things mentioned in Matthew 24, Mark 13, and Luke 21 would come to pass.

And so, from this perspective, it is obvious why the prophecy pundits and end-of-the-world rapture specialists are, and will always be, wrong.

They are projecting into the future things that have long since passed.

Footnotes

1. Similar examples among Protestant evangelicals or fundamentalists would be envisioning the apostles as speaking only in King James English or thinking of Jesus as a “Christian” in the same sense they think of themselves as Christians. Jesus was, of course, a very devout Jew and not a Baptist, Anglican, or Roman Catholic!

2. The classic study that proved this to be the case was German historian Walter Bauer’s Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity.

3. Most of the world’s 2.1 billion Christians are Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, or mainline (i.e. theologically liberal) Protestant. Most of these Christians do not hold to the dispensationalist form of fundamentalist Christianity.

4. For an excellent analysis and history, see George Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, Oxford University Press, 1980.

5. Hagee, an independent fundamentalist pastor, has even articulated what he calls “Christian Zionism” and has formed an organisation called “Christians United for Israel.” At one of that organisation’s events, Hagee and his group gave 7 million dollars to Israeli officials for various causes in support of the state of Israel. One wonders if Hagee has been as concerned to support his fellow Christians living in Israel. For more information, see the group’s website at www.cufi.org.

6. ESV is the English Standard Version of the Bible.

7. This is known as the “preterist” view, from the Latin term meaning “past.”

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.