From New Dawn 203 (Mar-Apr 2024)

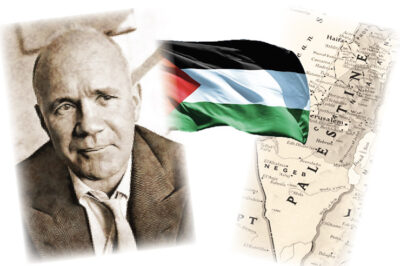

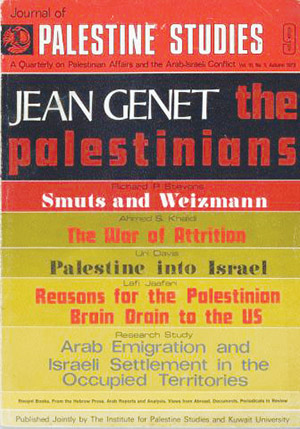

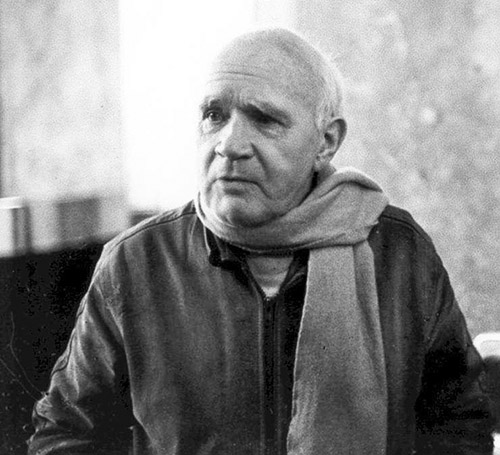

“If I were to be asked why I support the Palestinian revolution,”1 remarked French novelist Jean Genet in a piece for the autumn 1973 issue of the Journal of Palestine Studies, “I would recall that…. I realised that it had not only changed the Palestinians but also changed me.”

A member of the Palestine Liberation Organisation asked Genet in Paris to “visit the Palestinian camps and bases in Jordon” circa 1970, as did the Black Panther Party ask him, around that same time, to travel to the United States to join in a nationwide speaking tour2 promoting its social revolution.

Over five novels penned in the 1940s, Genet served as a voice for those living on the margins of French society – prisoners, thieves, sex workers, beggars – and in exposing a divergent moral order, he brought a humanity to the streets in his exposition of a literary Nietzschean revaluation of values.3

Following his US trip, Genet spent the six months to March 19714 in Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan, and it was there, amongst the Palestinian fedayeen fighters, that the writer found a social order, like that of French inmates, in which to revel and challenge the dominant paradigm.

Indeed, the themes traversed by the writer, who spent much of his early days imprisoned by the French state, in the three pieces he produced on the dispossessed indigenous people of Palestine, are similar to those being triggered by the Free Palestine movement challenging Israel right now.

Dispossessed by Europe

This article is being written on the hundredth day of the wholesale massacre that the settler colonial state of Israel has been perpetrating upon the 2.3 million Palestinians of Gaza. More than 23,000 mainly civilian Palestinians5 have been slaughtered, and those numbers include over 10,000 children.6

The state of Israel was founded in 1948 on the lands of the Palestinians after the British officially promised the region to the Zionist movement within the terms of the 1917 Balfour Declaration.7 This handover was to occur after Britain secured a mandate over Palestine following World War I.

Zionism is a nationalist movement, developed in the 19th century, that asserts a Jewish state be established in the land of Palestine and that nation, today’s Israel, is sanctioned by the authority of the Hebrew Bible. In fact, the current assault on Gaza is understood to be part of the Zionist project.

Early last century, the British, too, promised the Palestinians their land in exchange for their support against the Ottoman Empire, but as European powers carved up the region and established the League of Nations post-WWI, the Zionist deal was honoured, and the Palestinians were betrayed.

This set of circumstances was mirrored post-WWII when the League of Nations was replaced by the United Nations. In 1948, the Israeli state was founded, and the Nakba – the catastrophe – unfolded with around 750,000 Palestinians forcibly removed from their lands to make way for Israeli settlers.

As Genet describes it in his 1973 article ‘The Palestinians’,8 “the Jews had bought all the land in Palestine or driven out the population by terrorism – as if the Jews, arriving as they did with the support of European finance, had pulled away the land from beneath the Palestinians’ feet like a carpet.”

“Visit to the banks of the Jordan”

The ongoing genocide in Gaza has been termed the second Nakba or the continuing Nakba. The number of Palestinian casualties involved in the new catastrophe has now far surpassed the death toll9 of the 1948 Nakba, and, with this, the desire for further Israeli expansion is exposed.

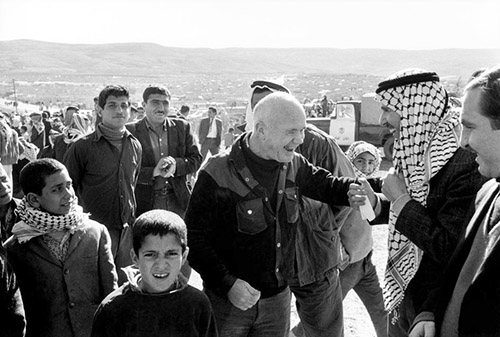

Genet arrived to stay in the Palestinian guerrilla camps at Jerash and Ajloun in Jordan in October 1970, straight after Black September, which was an armed conflict that broke out between Jordan’s King Hussein and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), then chaired by Yasser Arafat.

Genet’s ‘The Palestinians’ covers discussions he had with a group of Palestinians in Paris in 1972. But his greater work on his experiences in the camps, 1986’s Prisoner of Love,10 is said to have been loosely commissioned by Arafat11 as he supposedly asked the author, “Why don’t you write a book?”

“Not long after, in September 1970, when Hussein of Jordan was in danger of being beaten by the fedayeen, America came to his aid,” Genet recalls in his posthumously published memoir, Un Captif Amoureux in the French, which covers his time in Jordan, during a conflict that lasted until mid-1971.

“What made the fedayeen supermen was that they put the predicament of all before their own individual wishes,” the novelist wrote of the fighters he so admired. “They would set out for victory or death, even though each still remained a man alone with his own sensibilities and desires.”

Sabra and Shatila

On the invitation of a Palestinian friend, Genet visited Lebanon in 1982, which coincided with the Israeli invasion of the south of that country, which began in June and was based on the pretext of preventing PLO cross-border attacks on Israel and it included laying siege to West Beirut.

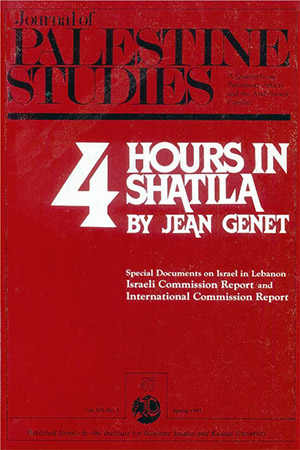

Ending on 18 September 1982, the three-day massacre of thousands of Palestinian and Lebanese people in the residential neighbourhood of Sabra and the refugee camp of Shatila shocked the globe in a similar manner to the current genocide in Gaza, yet on a much smaller scale.

The killing operation was perpetrated by right-wing Christian Lebanese groups sponsored by the Israeli Defence Force.

Genet was one of the first foreigners allowed to enter the Shatila massacre site. As Egyptian writer Ahdaf Soueif recounts in the introduction to Prisoner of Love, the Lebanese army took him into custody upon learning of his visit in an effort to ensure that he did not write about what he’d witnessed.

This reflects the western media coverage of the Gaza genocide, which has seen mainstream outlets producing sanitised Israeli-slanted versions of events since October, at the same time as Tel Aviv perpetrates multiple crimes against humanity, with western allies dismissing them as self-defence.

The French writer entered the refugee camp in order to capture the horror of the massacre, which isn’t usually captured by other means. The novelist described the dead bodies strewn across the refugee camp using the floral prose language that he employs across all of his works.

“A photograph doesn’t show the flies nor the thick white smell of death,” Genet writes in his 1982 essay ‘Four Hours in Shatila’.12 “Neither does it show how you must jump over bodies as you walk along from one corpse to the next.”

Confessions of a Thief

French society criminalised Genet at birth, even though it was not then apparent that the baby would grow up to be gay, with the writer having become aware of his sexuality in his early teens, as, at this time in Europe, if a person wasn’t heterosexual, they were breaking the law.

Having never known his father, Genet was abandoned by his mother at seven months old and then placed into foster care via a system of the day that saw adopted children dressed in a different uniform to that of their carers’ kids.

As Genet recounted to the BBC in 1985,13 at the age of 15 he was sent to the Mettray Penal Colony after having taken the train to Paris without a ticket. It was within the strict system of the reform facility that Jean found himself to thrive amongst the all-male cast of young “toughs.”

As was common for a boy in his situation, at the age of 18, Genet joined the French Foreign Legion, and during his years stationed in Syria and Morocco, he developed a deep affinity with Arab culture.

On being dishonourably discharged over having been discovered partaking in homosexual acts, the writer then spent several years as a vagabond travelling across Europe, supporting himself via sex work, begging and stealing.

On arrival in Paris in 1937, Genet was again arrested and sent to prison. He then spent the next twelve years in and out of jail whilst he wrote a series of books along the way. And in 1949, as he notched up his 15th conviction, he was served a life sentence as the local law of the day required.

However, a group of French intellectuals led by Jean-Paul Sartre and Jean Cocteau petitioned the French president, insisting that Genet was a literary genius, and, therefore, he should not remain in prison. This saw him freed, and he never returned to jail.

Over the 1940s, Genet wrote and published five novels. Notable titles include Our Lady of the Flowers, The Miracle of the Rose and The Thief’s Journal. The figures occupying the pages of his novels are sex workers, transgender people, queer people, pimps and murderers.

Genet then went on to become one of the four key playwrights of the post-World War II Theatre of the Absurd movement, penning titles such as The Maids and The Blacks. In a rush to beat the final hour, the French novelist pushed out Prisoner of Love just prior to his death from throat cancer.

A Seismic Shift

For Genet, the Palestinian revolution is the coalescing of Palestinian consciousness and resistance in the face of the Israeli invasion, takeover and occupation.

This brought about a personal revolution because he realised that in Europe, he viewed the function and not the person. An example of this was his viewing waiters as their function and not people. And the function of a waiter could easily be replaced by someone else if they were sick.

But “in the Palestinian bases the opposite happened,” Genet wrote in his 1973 journal article. “No man was exchangeable as a man. We noticed the man only regardless of the function, and the function was not a service to maintain a system, but a fight to smash a system.”

These social relations that existed within the Palestinian camps turned the French system of capital on its head, and this association formed part of Genet’s lifelong search for meaning outside of the mainstream. And it’s this drive for new meaning that’s being evoked by the current crisis in Gaza.

As the scale of Netanyahu’s extermination program became apparent months ago, much of the planet’s commentariat, starting with Palestinian scholars,14 found that the complete disregard Israel is showing for global norms likely marks the beginning of the end of the international rules-based order.

Indeed, the Global South has been looking on in disbelief as US President Joe Biden and western allied leadership lined up beside him to frame Israel’s crimes as self-defence. This stance reveals the naked hypocrisy of those who consider themselves the holders of the moral high ground.

In Our Thousands, In Our Millions…

In the face of ongoing Israeli atrocities, millions of pro-Palestinians have been rallying on the streets of urban centres globally. These outpourings of humanity have been persistently staged across the planet since October, despite western governments opposing them early on.

Much has been made by older antiwar activists at these rallies, and in the media that accompanies them, in regard to the massive anti-Vietnam war demonstrations of the 1960s, as they took much longer to mobilise than the pro-Palestinian movement of the present, which appeared in an instant.

Soueif recalls in her introduction that Genet was captivated by the Palestinian movement as it was the “antithesis of rigidity” and marked by “flexibility of… identity.” It was a campaign that could embrace all: “Cuban doctors, a French priest, a nun… a young Israeli who had renounced Zionism.”

This is another clear similarity with the current humanitarian crisis in the Gaza Strip, as the grassroots movement opposing this Israeli-perpetrated mass killing against Palestinians living within what is a walled-in region is not just made up of Palestinian agitators.

The Free Palestine Movement is supported by non-Zionist Jewish people the world over, as well as by the same types of left-wing, multicultural, multifaith, antifascist dissenters that filled the streets during the 2020 Black Lives Matter uprisings.

Indeed, this movement of today is the symbol of diversity, whether that be cultural, religious or in relation to sexual identity.

“A revolution which does not aim at changing me by changing the relations between people does not interest me,” Genet wrote in 1973 – fifty years prior to the current genocide in Gaza, which is serving to generate a massive social justice movement that incorporates diverse identities.

“The Palestinian revolution has established new kinds of relations which have changed me,” Genet said in a line that could serve to describe many in the present, “and in this sense, the Palestinian revolution is my revolution.”

Footnotes

1. The Palestinians by Jean Genet, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973), 3-34, jstor.org/stable/2535526

2. Jean Genet and the Black Panther Party by Robert Sandarg, Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Mar 1986), 269-282, jstor.org/stable/2784171

3. Nietzsche and the Re-Evaluation of Values by Aaron Ridley, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series, Vol. 105 (2005), 155-175, Oxford University Press, jstor.org/stable/4545433

4. youtube.com/watch?v=Cn7LWdmdyTU

5. middleeasteye.net/news/gaza-war-100-days-more-than-23000-dead-society-ruins

6. savethechildren.net/news/gaza-10000-children-killed-nearly-100-days-war

7. youtube.com/watch?v=vLIBZ1Fewco&t=619s

8. jstor.org/stable/2535526

9. vox.com/world-politics/23921529/israel-palestine-timeline-gaza-hamas-war-conflict

10. goodreads.com/book/show/85373.Prisoner_of_Love

11. radicalphilosophyarchive.com/issue-files/rp56_article3_writingtherevolution_critchley.pdf

12. Four Hours in Shatila by Jean Genet, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Spring, 1983), 3-22, jstor.org/stable/2536147

13. youtube.com/watch?v=Cn7LWdmdyTU

14. sydneycriminallawyers.com.au/blog/why-are-we-killing-children-gazas-horror-will-collapse-the-international-rules-based-order/

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.