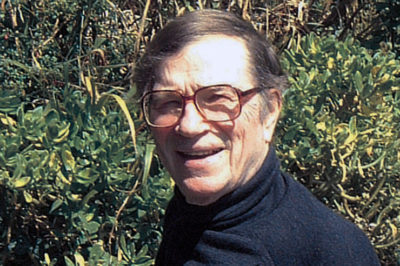

Colin Wilson passed away on 5 December 2013. A tribute to his life and examination of his work written by Colin Stanley appears in New Dawn 143 (March-April 2014). New Dawn Special Issue Vol 8 No 2, published in April 2014, contains an interview with Colin conducted by Australian writer Louis Proud. The following article was published in New Dawn on the occasion of Colin Wilson’s 80th birthday in 2011.

Whether we agree with him or not, Colin Wilson has to be one of the most challenging and stimulating writers of the last half century.

– Gary Lachman, American writer & musician

I have heard Colin Wilson speak in person only once. It was in 1987 or 1988, when he gave a lecture at the First Unitarian Church in San Francisco. The event was well-attended, with at least a couple of hundred people present. But what struck me most about the talk was the strange state of consciousness it inspired in me.

I had come in no special mood, and I remember nothing of the evening before or after. But I remember observing myself as Wilson spoke and finding myself possessed of a completely clear and attentive concentration. A great deal of the noise of the usual mental chatter was simply absent. At the same time I was alert and aware – I was not merely absorbed in the talk, as one can be in a particularly gripping movie thriller.

Because the state disappeared soon after the lecture ended, I can only believe that this peculiarly focused and alert attention was a reaction to something that Wilson himself was generating. I mention it here because this kind of concentrated attention is one of the central themes of Wilson’s work and thought.

Born in Leicester, England, in 1931, Wilson came from a middle-class background and as a teenager pursued a conventional education in the sciences. But at some point he discovered literature and philosophy, and he became so engrossed in these that he neglected his studies, dropping out of school at the age of sixteen. In the 1950s, he spent time among the political and intellectual circles of London, and for a while spoke at London’s famed Hyde Park Corner – the world’s capital for soapbox orators – on anarchical syndicalism. This was not, as he later admitted, because of any real sympathies for syndicalism but “because I was bored, frustrated, and had a vague feeling that something ought to be done about something. I also wanted to practise speaking in public, and would have been equally happy to discourse on Communism, Mormonism, or Nudism.” He also engrossed himself in an intense program of reading, which bore fruit in his first book, The Outsider, published in 1956.

The Outsider was a tremendous success, and won accolades from mainstream critics such as Cyril Connolly, who in the Sunday Times of London called it “one of the most remarkable first books I have read for a long time.” As its title suggests, this insightful and gracefully erudite book deals with what Wilson contends is one of the central themes of twentieth-century literature: the individual who is isolated, set apart, alienated from the crowd. He is typified by Meursault, the central character in Albert Camus’s The Stranger, who starts the novel by stating, “Mama died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.” Meursault’s affectless response to his mother’s death is followed by an equally impassive love affair and the killing of an Arab (the novel is set in Algeria). Although Meursault has committed the act in self-defence, his utter apathy during the course of the trial leads to his conviction.

Twentieth-century literature (and nineteenth-century literature to a certain degree) is teeming with Meursaults: Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Underground Man; Joseph K. in Franz Kafka’s The Trial, who is arrested, tried, and executed without even knowing what he has done; and the bored and alienated scholar Antoine Roquentin, hero of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea – all of whom Wilson discusses in The Outsider.

As this brief list suggests, The Outsider reflects Wilson’s interest in existentialism. To most people today, existentialism is more of a mood than a philosophical system. One thinks of gloomy French intellectuals in smoky cafés, immersed in opaque but inevitably pessimistic discussions. But existentialism means something quite specific in philosophical terms. Unlike Thomas Aquinas and other Aristotelian philosophers who came to dominate Roman Catholic philosophy, the existentialists argued that man has no essence – that is to say, there is nothing he is at his core that God has created (most forms of existentialism are radically atheistic). Or rather, man’s essence is derived from existence, from his actions in the world. Because God has not made man in any particular way, man is free. If he feels he is not free, this is only because he has failed to acknowledge his own freedom.

The notorious pessimism of the existentialists comes from the idea that man’s freedom is the result of his existence in an alien and indifferent world. There is no intrinsic meaning in the universe, because there is no God who created it. It is up to man to make his own meaning.

Unfortunately, as Wilson recognised, this stance creates problems. You can take up carpentry to while away the time, but can you create meaning and purpose for your own life as you might make a workbench? Some of the existentialists – particularly Sartre – may have thought so, but Wilson argues that this creation of meaning, while necessary, cannot be accomplished just by taking up a cause at random.

Wilson also displays a deep affinity with another, less well-known twentieth-century philosophical school: phenomenology. While phenomenology is a vast and intricate system none of whose primary exponents completely agree, it contends that all consciousness is intentional; it is toward something. Explaining the thought of Edmund Husserl, the founder of the school of phenomenology, Wilson writes, “All mental activities are essentially acts, analogous to reaching out one’s hand or shooting an arrow at a target.” Indeed, he adds, “the mind has no equivalent of the non-intentional act – even becoming unconscious under anaesthetic” (emphasis here and in other quotes Wilson’s).

Existentialism and phenomenology set the stage for Wilson’s mature thought, but it is perhaps with the great twentieth-century sage G.I. Gurdjieff with whom he has the deepest affinity. Wilson discusses Gurdjieff in The Outsider, in his 1970 book The Occult: A History, and in other works, including Gurdjieff: The War against Sleep. Indeed, Wilson contends, “Gurdjieff’s system can be regarded as the complete, ideal Existenzphilosophie [existentialist philosophy].” Why? Because it shows a genuine and realistic way to rise up from the sleep of ordinary, habitual life – the boredom and alienation that are the marks of the existentialist antihero – and awaken into a higher dimension of experience.

As Wilson points out, one of the central disciplines in Gurdjieff’s teaching is “self-remembering” – which Wilson describes as follows: “Normally, when you are looking at some physical object, the attention points outwards, as it were, from you to the object. When you become absorbed in some thought or memory, the attention points inwards. Now sometimes, very occasionally, the attention points both outwards and inwards at the same time, and you find yourself saying, ‘What I, really here?’: an intense consciousness of yourself and your surroundings.” It may have been Wilson’s own self-remembering that stimulated a similar response in me during that lecture over twenty years ago.

It is this self-remembering, this awakening, deliberate or inadvertent, that Wilson discovers in many account of mystical experience. Gurdjieff might have agreed. When asked once what higher consciousness was like, he replied, “Everything more vivid.” For Wilson, this awakening is the gateway to what he calls Faculty X, which he calls “the power to grasp reality,” and which “unites the two halves of man’s mind, conscious and unconscious.”

Wilson argues that “Faculty X is the key to all poetic and mystical experience; when it awakens, life suddenly takes on a new, poignant quality. Faust is about to commit suicide in weariness and despair when he hears the Easter Bells; they bring back his childhood, and suddenly Faculty X is awake, and he knows that suicide is the ultimate laughable absurdity.”

It is Faculty X, and Wilson’s exploration of it, that provides the key to much of his writing, which over the years has ventured further and further into the waters of the paranormal. For Wilson, Faculty X does not lie in some distant evolutionary future, when the human race will have evolved capacities that now seem preternatural; it is something we possess in latent form now, and which in fact our remote ancestors may have possessed in the past, when the human mastery of the physical world was far less complete and when people had to rely on inner resources for tasks that we now entrust to machines.

But Faculty X has more than merely pragmatic value. When it is awakened, it provides an intensity of experience, a lived reality that not only makes “everything more vivid” but provides the added dimension of meaning for which the existentialists pined so acutely – and which forms what may be the point of focus for Wilson’s voluminous writings. If there is a thread that holds together a body of work that comprises over one hundred published books, it is, I suspect, Faculty X and the strange sense of vivid concentration of which I had a glimpse over twenty years ago.

How do Wilson’s insights look today? We live in a time of change, which continues to accelerate to the point of destabilising not only nations and societies but the individual soul. There is a fascination with new technologies – with iPads and Facebook – that seems to take us away from the issues of meaning and presence that Wilson emphasises so strongly. But if these novelties distract us from the existential questions that face us, they neither answer these questions nor remove them. At best they are diversions, like a film or a game of chess, which might take our minds off our problems for an hour or two but which leave the problems waiting for us when they are done. Even politics and world affairs, I suspect, serve as this kind of entertainment for many.

I believe that Wilson is right. If we are to win the war against the sleep of everyday life, it will not come out of technology nor even from political or social reform, as much as this may be needed. It will come from the liberation of individuals who awaken from the dreams that pass across their televisions and computer screens – and their minds – and are able to say, “I – here now.”

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.