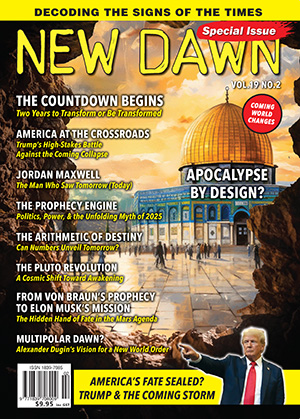

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 19 No 2 (April 2025)

As I write these words, Donald Trump has been President of the United States for just over a month. Most of the voters who put him into office are delighted by what his administration has accomplished so far. The exceptions are those who don’t think he’s done enough to slash the permanent bureaucracy of Washington, D.C., or those who are disappointed that arrests and trials haven’t happened yet.

His opponents in the bureaucracy, the corporate media, and the classes that support the former status quo in the United States are yelling in predictable outrage, but the sound and fury has so far signified very little. Trump’s quick action against USAID, which funded most of the protests and legal challenges that made his first term so difficult, seems to have dealt a body blow to the opposing side.

Outside the circles of Trump’s supporters and opponents, however, a great many people seem to be baffled by the speed at which Trump’s administration is moving and the unexpected nature of some of his initial targets. Even among his supporters and opponents, not many people seem to have grasped the logic of his moves or the agenda that lies behind them. Now, of course, quite a bit of that lack of comprehension comes from the bad habit, common on all sides of today’s politics, of treating complex struggles as though they were third-rate Star Wars knockoffs.

Most of us are wearily familiar with this habit. No matter who’s speaking and how much privilege they have, the side they favour is always supposed to be the heroic rebel alliance and the side they detest is just as inevitably the evil empire. Approaching anything from so simple-minded and cartoonish a perspective as this is a good way to be blindsided by the obvious.

Donald Trump is no more the Emperor Palpatine than he is Luke Skywalker. Instead, he’s a smart and ambitious member of the American ruling elite who saw an opportunity, took advantage of it, and – like so many people in the last decade – was radicalised by the dysfunctional and abusive behaviour of a system in terminal crisis.

Most people recognise that the industrial nations of the West are in trouble. Few have grasped just how deep that crisis goes, much less come to terms with the consequences. Donald Trump appears to be one of the exceptions. Whether he’s had the necessary insights or simply listens to people who have done so, he’s taking actions that only make sense if the predicament of our time is understood clearly. To grasp that, however, we’ll need to glance over some theory.

The Threat of Catabolic Collapse

As I explained two decades ago in my paper “How Civilizations Fall: A Theory of Catabolic Collapse,” the reason civilisations fall is a direct consequence of the process through which they rise. Societies of every kind grow by building up what economists call “capital.” This simple word embraces every product of economic activity that can be used to foster more economic activity. Obviously, a factory building is capital, and so are the tools inside it, whether hand tools on workbenches or industrial robots and the computer system that runs them. Roads are capital, so are the vehicles that drive on them, and so are the oil wells, refineries, pipelines, and petrol stations that keep those vehicles fuelled.

Capital also takes less concrete forms. A trained workforce is capital, and so are the hospitals where children are born, the schools where they become productive members of society, and all the other things they need to reach adulthood and join the labour force. Scientific laboratories are capital, so is the knowledge that comes out of them, and so are the libraries, journals, and websites that make that knowledge available. Markets are forms of capital, and so are the practices and ways of thinking that make them work. So, it bears noting, are bureaucracies.

Anything can be capital as long as it can be used directly or indirectly to produce more wealth. Of course, capital can be used efficiently or inefficiently. It can even fail to produce any wealth at all if it’s poorly managed. It remains capital as long as it can be used to produce wealth. Again, bureaucracies come to mind here.

The downside of capital is that it has to be maintained, and maintaining it requires the same inputs as the production of new capital. In this way, the cost of maintaining existing capital competes with all the other requirements of economic life, from putting food on tables to research that might open up new possibilities for the future. When the burden of maintaining existing capital becomes heavy enough, societies face a stark choice between abandoning some of their existing capital and going under.

This choice becomes even more difficult when economic activity depends on something other than capital: in the terms I used in my essay, resources. Like the word “capital,” the word “resources” here covers a lot of territory. It includes everything that comes into the economic process from outside. Fossil fuels and metal ores belong in this category, obviously enough. In addition, and crucially, the resource base for a society includes things produced by economic activity in other societies if those things are brought into the resource base by some means other than fair trade. The plunder seized by conquering armies becomes part of their nations’ resource base. So does wealth seized by less obvious means – for example, the transfer of wealth from client states to an imperial nation through the latter’s control of the global reserve currency.

What makes resource dependence a trap is that most resources are unsustainable, and the more concentrated and valuable they are, the more unsustainable they tend to be. Conquering armies can only plunder a kingdom so many times before there’s nothing left to loot. An imperial nation that uses its currency to extract wealth from client states will find itself in the same predicament, though it takes a little longer. Fossil fuels and metal ores deplete as they are extracted, and the costs of continued extraction climb steadily while the output falls.

Steady economic growth thus requires the replacement of resources with capital. Farmers found this out centuries ago when they discovered that they had to maintain their soil to keep it fertile; in terms of the model we’re using, they turned a resource into capital and got sustained yields in exchange for paying the maintenance costs of the soil. In exactly the same way, we provide tax credits for families with children rather than importing slaves from conquered nations; the workforce of a nation is a form of capital and has to be maintained.

Relying on capital rather than resources is thus a strategy with a long shelf life, but it has costs. Relying on resources is cheaper in the short run, but once the resource base is depleted, the society that takes that route is in deep trouble. It can only maintain economic activity by treating its capital as resources, cannibalising it in order to keep the economy going a little longer. The result is catabolic collapse – the process by which falling societies consume their capital in the process of going under.

That’s what the United States is facing today.

On the Brink of Catabolic Collapse

A society that has become dependent on extracting resources from outside itself rather than using its own carefully managed capital to drive economic activity has few options once the limits to resource extraction start to bite.

The first thing almost every society tries in this situation is to find new resources to exploit. That attempt can be made through territorial expansion as when an empire that has drained all the portable wealth from its existing provinces conquers a neighbouring kingdom not yet stripped of wealth. It can be made through technological innovation, as when the invention of the steam engine turned coal from a mildly useful fuel to the essential energy source of an age.

The quest for new resources can be pursued in other ways, but all of them have a fatal drawback: the law of diminishing returns. Sooner or later, the empire conquers and loots every kingdom within reach – which was what happened to the Roman Empire. Sooner or later, for that matter, the scientific thought of every civilisation runs up against its own limits and those of its environment, and it becomes harder and harder to replace natural resources as fast as they’re being used. This is an important part of what’s happening to industrial society today. Each of the other options has similar drawbacks.

When the quest for new resources fails, catabolic collapse comes within sight. The next step failing societies take, once resource intake starts falling off, is to neglect to pay the maintenance costs for whatever existing capital is considered expendable. That frees up wealth for more crucial needs, but it always brings costs of its own. Nor is the leadership of a failing society necessarily a good judge of what capital is actually expendable.

Crisis arrives when declining resource inputs and malign neglect of capital maintenance combine to send the economy into a crash dive. Facing disaster, few elites can resist the temptation to cannibalise existing capital as though it were a resource base. This simply postpones the inevitable for a little while at the cost of making the decline more severe.

As crisis follows crisis, more and more of the society’s capital gets used up in the struggle for survival, leaving a dwindling capital stock to support all other economic activity. This is the process that turns thriving societies into small communities of shell-shocked survivors huddled in the ruins of an earlier age. It’s the process that turned the Roman Forum into a goat pasture and left the great Mayan cities to be overgrown by the jungle.

As a society approaches catabolic collapse, only one strategy works to pull out of the dive before it’s too late. A very large amount of capital has to be abandoned as quickly as possible, slashing maintenance costs and freeing up the remaining capital for productive uses. This is how the eastern half of the Roman Empire survived the crisis that overwhelmed the western half. By cutting loose the western Empire, which had most of Rome’s threatened borders, and abandoning all the capital in that half of the empire – including the city of Rome itself! – the eastern half, which accounted for most of the economic production, freed up enough of its own capital to survive for a thousand years after Rome fell.

This, in turn, is what Donald Trump and his administration are trying to do in the last inglorious days of America’s imperial adventure.

The End of American Empire

The United States came out of the Second World War in a position of unique global power. Unlike any of the other major combatants, it had kept its homeland secure from bombing raids or outright invasion; its industries accordingly dominated the global economy, and its abundant natural resources gave it even more economic clout; in 1950, it bears remembering, the United States produced more crude oil than the rest of the world put together. That position of power made it easy for American elites to use the wartime Bretton Woods agreements to make the dollar central to global trade and impose a form of “stealth imperialism” on most of the rest of the planet. So vast was the flood of resources this brought into the American economy that for most of the second half of the 20th century, the 5% of the global population that lived in the United States consumed one-quarter of the world’s energy input and natural resources and one-third of its manufactured products.

The history of the last fifty years has been shaped by the unravelling of those arrangements. The reasons for that unravelling would have been painfully familiar to any Roman statesman. Attempts to get more resources for the US by invading Iraq, for example, worked no better than the Roman attempt to get more resources by invading Parthia. Malign neglect accordingly spread through the American economy as maintenance costs of capital were neglected: the dismal state of US roads and bridges, the shameful condition of its educational system, and the ragged but ongoing declines in measures of public health are among the symptoms of this process.

As the third decade of this century began, the only viable option for the long term was for the United States to get out of the empire business, jettison its imperial commitments overseas, cut the gargantuan bureaucracy that had grown up around its imperial project, and retool its economy to live within the means of its still bountiful territory. Unfortunately, this was not something the elite groups in control of the US political system were willing to consider. Even more unfortunately, they thought they had an alternative: the conquest of Russia.

That has been the subtext to American and European elite manoeuvrings in eastern Europe for decades, especially since 2014 when the US and its allies staged a coup in Ukraine, overthrew its elected government, and put in a new government hostile to Russia. Look at the publications of American and European defence think tanks and you find the plans for all this, complete with maps showing the weak and vulnerable successor states into which Russia was to be partitioned. Those successor states would then be absorbed one after another by the European Union so that Russia’s lavish natural resources could be plundered efficiently by Western multinational corporations and used to prop up the failing American imperium.

The fatal weakness of the plan became clear in the months after the Russo-Ukrainian war broke out in 2022. Western elites assumed that they were still dealing with the brittle mess that Russia had become in the immediate wake of the Soviet Union’s fall. Their expectations were fatally past their pull date. After initial fumbles, the Russian military found its feet and settled into a war of attrition, the kind of conflict at which Russian forces have always excelled. Meanwhile, even with lavish subsidies from the West, the Ukrainian forces failed to mount strategically effective counteroffensives and were driven back across the Donbass by the Russian onslaught.

That, more than anything else, made Donald Trump’s victory in the 2024 election inevitable. The policies set in motion by the Washington establishment under Obama and pursued with increasing desperation under Biden have failed. Accordingly, a substantial faction of American elites turned to the one remaining alternative and rallied around Trump. The changes now underway in Washington, D.C., and around the world are the first steps in the massive realignment that such a change, of course, requires.

The Struggles Ahead

The task facing the Trump administration in the months ahead is roughly twofold. The first and easiest half consists of trimming the US federal government to a size that can be sustained by the more limited budget of a post-imperial America. To some extent, this is made easy by the sheer scale of fraud, corruption, and misuse of funds in Washington, D.C., and also by the metastatic growth of administrative staff in federal bureaucracies, most of which can be cut without the least impact on the actual functions of government.

What the political slang of an earlier time called by the endearing label of “pork” – that is, expenditures that benefit politicians and their cronies rather than serving any useful purpose – also make up a huge share of the federal budget. Eliminating pork from the budget altogether is almost certainly out of reach, but it can be trimmed substantially. All of this will free up wealth that can be used to maintain and rebuild the nation’s neglected capital.

The more challenging half of the work consists of the retreat from overseas empire. The most obvious target for cutting here is out of reach for reasons rooted in domestic politics. The nation of Israel only survives because it is propped up by lavish US subsidies, but the United States has a larger Jewish population than any other country on earth, and the American Jewish community is well-organised enough to have an outsized effect on elections. Until and unless that changes, subsidies for Israel will remain sacrosanct in Washington, D.C.

America’s other erstwhile allies lack that protection. Western Europe is especially vulnerable, partly because its nations no longer have large émigré communities in the United States that identify with the “old country,” partly because the elites of the western European nations remain overcommitted to the failed project in Ukraine, but also because of those same elites’ shrill hostility to Trump and his policies. At a time when the EU no longer has access to cheap Russian resources and is losing its neocolonial grip on sub-Saharan Africa, alienating the leadership of the US is not exactly a smart move for the EU, but no law of nature requires politicians to make good decisions.

One way or another, the age of the US global empire is ending. If the Trump administration succeeds in its project, that end may be much less traumatic for American citizens than it would otherwise be. At the same time, that project faces robust opposition in the United States and abroad, and its success is not guaranteed. Therefore, the next few years are guaranteed to be a tumultuous time with an uncertain outcome for America and the world.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.