From New Dawn 123 (Nov-Dec 2010)

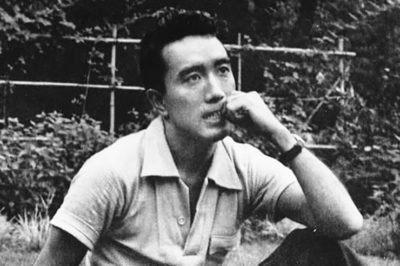

Yukio Mishima (pen name of Kimitake Hiraoka) is perhaps the most commanding and tragic figure in 20th century Japan. Born into a samurai-bureaucrat family in 1925, he committed ritual suicide (seppuku) on 25 November 1970. He had just failed, predictably, in a call on the Japanese Self Defence Forces to revolt and re-establish the traditional authority of the Japanese Emperor. Mishima was at the peak of a brilliant literary career and on the day of his death he had completed the fourth and final volume of The Sea of Fertility, summing up his vision of the Japanese experience in the 20th century.

Mishima’s life and work seems to be a continuous exercise in yin and yang, exploring the mutually nurturing activity of complementary (or contending) qualities like beauty and destruction, pride and shame, strength and weakness, loyalty and betrayal, sacrifice and indulgence. Of even more weighty and lasting importance, his work appeals as an exhaustive and exhausting exploration of mythologies that might revive and reinvigorate the Japanese spirit. Nothing was more important or more taunting after Japan’s humiliation and devastation – the result first of Western socialisation and second of Western conquest.

No one could better represent and articulate the burden borne by the Japanese elite in the 20th century than Mishima. He won a citation from the Emperor as the highest ranking honour student at graduation from the Peers’ School in 1944, as Japan approached defeat and humiliation. He graduated from Tokyo Imperial University School of Jurisprudence in 1947, as Japan accommodated an alien occupation. He then joined the Ministry of Finance at the pinnacle of Japanese government and published his first novel in 1948. His samurai family’s code of complete control over mind and body, loyalty to the Emperor and the austerity and self sacrifice of Zen pervade his life and writing.

The maturing years of a puny and youthful Mishima make it possible to see him as a mirror for the post-war growth of a weak, bewildered and defeated Japan. Both progressed through much painful soul-searching to build their strength and emerge, at least temporally, as giants in the Asian consciousness.

Mishima’s life is a little less exotic than his stories. As a young boy he was captive to the needs and whims of a possessive grandmother with aristocratic airs. Nothing could better reflect the strict hierarchical and authoritarian values of his family and society or, perhaps, better nurture a young literary genius. His youth was a struggle towards self-assertion and self-empowerment in a competitive school environment where respect was not won easily and where his unmanly literary interests could invite aggression. Some coughing at his physical examination after being called up for military service gained him a diagnosis of incipient tuberculosis and a reprieve. He emerges as an elite bureaucrat, only to sacrifice that to become a widely celebrated novelist.

His qualities of self-discipline and self-motivation rarely appear outside their social and political context. His later emergence with a strong and muscular, even beautiful body, all the product of dedicated discipline and purpose, is easily seen as the ultimate expression of a refined and socially conscious human being, albeit in a samurai spirit. The semi-military scenes with his “private army” appear as a statement of a profound determination not to lose touch with the political and historical processes of his time. Even his writing, undertaken to a strict schedule each evening, appears almost as part of a military routine. The odd homosexual dalliance and humiliation was hardly a distraction – seemingly subject to severe, if sensitive, formalities. Indeed, his homosexuality possibly reflected a military culture of encouraging same sex liaisons as a means of strengthening battlefield loyalties.

Discovering Asian Civilisation

40 years after Mishima’s death, I encounter a personal set of contradictions and confusions in re-examining and attempting to re-evaluate his life and work. I arrived in Tokyo in 1964 as a diplomatic language student and left in 1969. At a time that was critical in my discovery of Asian civilisation, Mishima loomed large in my imagination as the living embodiment of Japanese cultural and political consciousness. He loomed even larger when I was cross-posted to Laos where his brother was serving as First Secretary in the Japanese Embassy, only to be replaced before my arrival by another officer married to the sister of Mishima’s wife, evidence of the close-knit character of the elite Japanese bureaucracy.

Mishima’s subsequent samurai seppuku while I was still in Vientiane provided a taunting comment on the Indo-China War, which was the focus of my then professional duties. Unlike the Pacific War where it defeated Japan, America did not succeed in the Indo-China War in defeating Vietnam. This echoed many of the troubling contradictions that haunted Mishima’s life.

Mishima observed all the correct forms of Japanese surrender yet explored in the most relentless and captivating manner the need to keep the Japanese spirit alive until the time came to express his convictions in actions rather than words – actions that are likely to echo into the future as long as there is art and as long as there is a Japanese spirit. Moreover, perhaps no contradiction was more profound than Mishima’s criticism, common in his writing, of the Japanese capitalists who had usurped the authority of the samurai ethos.

It is possible to see Mishima, his colleagues in the Ministries of Finance (and Foreign Affairs), and Japan’s capitalists all observing the same disciplined, politically correct forms of surrender, while all discreetly working in their own ways towards a victory (initially commercial) over an America that had humiliated Japan in war. By the end of the 1980s, American authors in books like Japan as Number One were warning of a possible Japanese victory that Mishima was most unlikely to have foreseen.

These personal recollections and reflections and my own voyage of discovery of an even larger and more dynamic Asia, where China has taken a leadership role once thought reserved for Japan, cannot but colour the way I approach any evaluation of Mishima’s legacy. It places that legacy inescapably in the context of my own exploration of the remarkable character of East Asian civilisation and its economic and cultural renaissance over the past half century. During the four decades since Mishima’s death, I have become acutely aware of fundamental differences between an Anglo-American global order that has largely defined the past two centuries of global history (and all of modern Australian history) and an ascendant East Asian Confucian order likely to define the indefinite future.

My recent reading of Thinking from the Han: Self, Truth and Transcendence in Chinese and Western Culture by the American authorities on Chinese civilisation, David Hall and Roger Ames, is of particular relevance to my recollection of Mishima. The idea of “self” often looms large for those who examine Mishima’s life and work from a Western perspective. Yet “self” seems to misrepresent totally the essence of Mishima’s life in the Japanese and East Asian environment. Mishima was unquestionably a product of Japan’s intellectual and administrative samurai aristocracy, whose energies and talents are today concentrated in achieving educational and intellectual excellence. The sentiments he evoked are unlikely to die away simply because China and Vietnam have won overt political successes seemingly denied Japan. At the same time, I suspect that Mishima’s elite colleagues and successors, now more than ever defined by relentless academic competition, will find more in common with counterparts in China, Vietnam and elsewhere in Asia than with partners distanced by vast oceans and even vaster cultural divides.

Mishima and His Work

Any choice of particular works from Mishima’s voluminous output will be invidious. Nominated three times for the Nobel Prize, Mishima wrote 40 novels, 18 plays, 20 books of short stories, at least 20 books of essays, one libretto and one film. More than 20 of his novels have been translated and published in English. The richness, maturity and insight of his work from an early age often make it difficult to place without careful thought a work in a particular period of his life. All were characterised by the heroic efforts of their protagonists to find a meaningful mythology for their own physical lives in a bewildering kaleidoscope of unrelenting and unpredictable cultural, social, and political change. Almost invariably, this was laced with various physical and spiritual temptations. A quick review of a few of these works offers a glimpse of Mishima’s virtuosity.

It is surprising, for instance, to realise that a book like Forbidden Colours, which demonstrates Mishima’s uncompromising character in searching out the most difficult and confronting issues in human experience, was written when he was 28. This was the age at which I arrived in Tokyo, green, immature, inexperienced and ill-equipped to envisage such a reality, despite a university education in Russian and English literature.

A brief outline of the story offers a glimpse of the author’s mastery of the darkest recesses and greatest heights of Japanese society in the immediate post war years.

This major novel, regarded in Japan as Mishima’s masterpiece, is as much a vivid and shocking panorama of the corrupt life of Tokyo five years after the end of the war and an attack on oppressive Japanese marriage customs as it is the affecting story of Yuichi Minami, a handsome young man with homosexual inclinations.

Yuichi is caught between his impulses and the demands of his family. Out of his loveless marriage his anguished homosexuality burgeons, and his wife’s dreams depart. The first chapter irresistibly brings to mind “Death in Venice.” An old and famous writer is captivated by Yuichi, and like Mann’s Aschenbach he is never again the man he was. He becomes Yuichi’s mentor, spouting satanic philosophies much like those Oscar Wilde imparted to the young Andre Gide.

He persuades Yuichi to pursue and disappoint a number of beautiful women who have slighted the writer. Yuichi involves himself with lovers young and old, male and female. We meet ex-aristocrats dabbling in the black market, newly rich couples living promiscuously, blackmailers and male prostitutes. There are remarkable descriptions of parks of assignation, of gay bars and of gay parties, often frequented by Americans. The signs, the argot, the evasions, the frustrations, the humour, the joys and the tragedies of this strange and hidden world are brought out with sympathy and great candour, but also with irony and aversion.

The richness of Mishima’s adventures can take the reader on a voyage of discovery into a world rarely imagined but full of taunting truths and undeniable realities. Many readers are likely to be left haunted by previously unimagined human interaction.

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion was written three years later and captures the trials of another young man, Mizoguchi, who is disabled by a crippling stutter but is fascinated by the beauty of the Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Taken by his dying father, a poor rural priest, to become an acolyte at the Temple, he has heard throughout his childhood about its splendid beauty. But the beautiful things in his new life as a monk – the temple, sexual possibility, and personal autonomy – leave Mizoguchi feeling overwhelmed and insignificant, until he seeks to resolve his painful perplexity by burning down the Temple of the Golden Pavilion. It is not hard to see in it a theme that runs through much of Mishima’s work – namely a fascination with beauty leading to destruction, often self destruction.

Three years later Mishima wrote Kyoko’s House, which was not well received and has not been translated into English. It explores four sides of Mishima through the stories of a boxer, a painter, an actor and a businessman. The American film director Paul Schrader has made the story of the actor available to English speakers in his film “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters.” Interestingly, it was only included after the writer’s wife objected to the use of Forbidden Colours. The actor’s story is, however, just as confronting as any of Mishima’s other stories. It tells of an actor who becomes involved in a sado-masochistic sexual relationship to settle his mother’s debts. This plunges him into a double suicide for himself and his lover, his mother’s creditor. There is less of a sense of rarefied spirituality, fascination with beauty and struggle against carnal debasement than in The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, highlighting Mishima’s capacity to move amongst all areas and levels of society. He seems to have an unlimited ability to discover and reveal the grand dramas being played out in mundane life. The actor seems totally absorbed in carnal pursuits and yet to be willing to literally give up his life for both his mother and lover. This heroic dimension does not loom as large as the garish décor of the mother’s bar and the trivia of the dialogue. The pact to commit a dual suicide is entered into almost as a casual convenience. Described as “terrifying” by Mishima’s biographer and translator, John Nathan, the novel’s importance to Mishima was reflected in the unprecedented fifteen months it took to write and the fact that, unusually, it was not published in magazine instalments. It is reported that poor sales and reviews hurt him seriously.

The following year (1960), Mishima wrote After the Banquet. Uncharacteristically, it is a story about a successful, worldly, head strong, older woman. She runs a business in the “water trade” and throws her heart and her money into a marriage with an aging, idealistic but naive aristocrat. When her support for his political aspirations becomes a source of conflict, highlighting irreconcilable values and life experiences, she has no practical option but to return to her trade – tending commercially the physical and psychological needs of her aristocrat’s political rivals. She again serves the very forces she had hoped to assist her idealist to defeat. The story can be described as a clash of love, politics and money but it also gives Mishima the means to explore characters and political activities that are rare in his work, offering an intriguing insight into the nature and processes of Japanese politics. The accuracy of Mishima’s story was subsequently confirmed by a successful law case mounted for invasion of privacy.

Mishima followed this fine account of confused ideals and political machinations in Tokyo the next year with a work described by one reviewer as “barbaric lyricism.” The Sailor who Fell from Grace with the Sea (“Afternoon of Glory” reflects the Japanese title more accurately) can be expected to shock almost any reader. A group of adolescent boys resolve to revenge themselves on the sailor who disappoints their romantic sense of masculine life at sea by falling for and committing himself to the mother of one of them. The erstwhile hero is seduced by the boy’s apparent adulation to subject himself to the cruellest of fates, all depicted in Mishima’s finely crafted poetic style.

This brief sampling of some of Mishima’s stories cannot reproduce his evocative and beautiful imagery or the way in which his genius invariably draws one into new and unfamiliar worlds in the most convincing ways, only to then present a shocking, almost unbelievable, conclusion. Desire and resentment are never far apart and one is often left asking questions that have never previously been encountered.

It has been suggested that Mishima’s psychological exploration is so profound that it is possible to find in his stories an account of the obsession, the hopelessness, and the desperation inspired by types of spiritual purity that can motivate acts of terrorism. Rather than focusing on terrorism, however, I believe it is more accurate to see Mishima’s writing as an exploration of the obstacles and confusions that confront all human aspiration. He creates a sense of the great difficulty encountered in reconciling ideals nurtured by a lofty human imagination with the mundane, perplexing and corrupting realities of existence.

The Sea of Fertility

“The Sea of Fertility” (a reference to the Mare Fecunditatis, a “sea” on the Moon) is the four volume work that Mishima completed on his final day. It contains Spring Snow (1966), Runaway Horses (1969), The Temple of Dawn (1970) and The Decay of the Angel (1971). It stretches from 1912 to 1975 and in all four books uses the viewpoint of Shigekuni Honda, who matures from a law student to a wealthy retired, but world weary and desiccated, judge. Honda’s life focuses on four reincarnations of his school friend Kiyoaki Matsugae and his attempts to save them from early deaths. This results in Honda’s personal and professional embarrassment and eventual destruction, somehow symbolic of those who cannot rise above the inevitable corruption of respectable social goals. The ill fated Matsugae is successively a young aristocrat, an idealistic nationalist, an indolent Thai princess and a manipulative and sadistic orphan. Significantly, the idealistic nationalist foreshadows Mishima by committing seppuku, but after assassinating a prominent symbol of Japanese leadership. Described by Paul Theroux as “the most complete vision we have of Japan in the twentieth century,” the book reflects Mishima’s endless quest to explore and comprehend the workings of individual lives in the destructive context of contending and conflicting certainties.

Some Concluding Thoughts

For a foreigner who studied Japanese language and remains committed to trying to comprehend the powerful sense of civilisation that defines East Asia, Mishima has always represented an irreplaceable source of insight and inspiration. His exotic and defiant character seemed to guarantee an incisive, authentic quality that is usually difficult to find. Today’s problems of globalisation and recurring crises in the West give, perhaps, extra dimensions to Mishima’s thought.

My memories of the mystique surrounding the living Mishima – the vital symbol of the Japanese spirit in the aftermath of defeat and occupation – manifests itself in almost infinite forms in his work. His task was made all the more problematic for someone with an elite sense of leadership responsibility at a time when the national character was burdened with a sense of defeat, humiliation and dishonour at the hands of an alien conqueror. Mishima’s achievement reflects the disciplined and self-effacing manner in which Japan accepted its defeat, apparently subjecting itself to all that it had fought so fiercely to reject.

This quality of disciplined, self-sacrificing purpose, in the midst of all the temptations and confusions of modern life, is central to Mishima’s legacy. It is a quality that has distinguished the Vietnamese in Indo-China and the Chinese under Mao and his successors. It is a quality that has been taken from the Confucian tradition throughout history and throughout East, and also South East Asia, although often in a form that is not immediately recognisable. In Mishima’s case his energies were dedicated to recording in a highly literate and informed manner the toils of the Japanese soul in the aftermath of defeat and occupation. In this he reflected a complex sense of community awareness, a quality of literary and educational excellence and a depth of intuitive discipline that characterises Confucian civilisation, even when given a unique form of Japanese relevance.

One must regret that Mishima is not alive today, wrestling at the age of 85 in his inimical way with the economic resurrection first of Japan, then of many other parts of Asia and finally of China. Most interesting would be his perception of an accompanying cultural renaissance that has been made possible by the victories of a leadership class of which he was critical.

Would he find contemporary public notions of reform in Japan out of touch not only with his preferred Japanese traditions but also with an emerging mainland rejection of Western fashions and the rediscovery and reinvention of values close to those that he lamented had been swept away forever by the tide of Western modernisation?

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author. For our reproduction notice, click here.