From New Dawn 191 (Mar-Apr 2022)

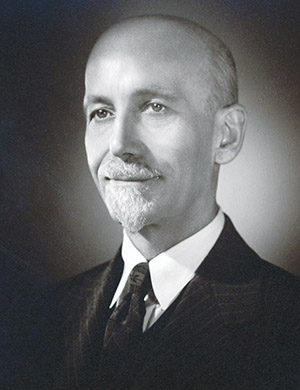

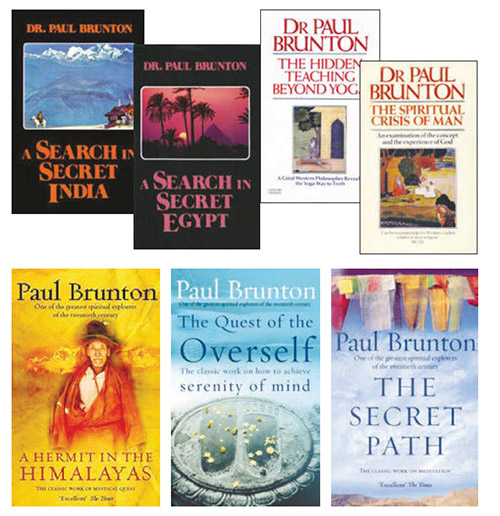

There was a time when Paul Brunton (1898-1981) needed no introduction. From the 1930s through the 1950s, his eleven books were best-sellers in the field of alternative spirituality. A Search in Secret India and A Search in Secret Egypt played to a popular fascination with the Orient.

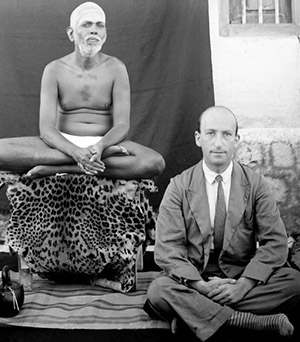

In Egypt, Brunton capped his meetings with magicians, snake-handlers, holy men and impostors by spending a night in the Great Pyramid, which he attributed to the Atlanteans. His Indian quest culminated in the encounter with Sri Ramana Maharshi, a living exemplar of Hinduism’s highest philosophy, that of Advaita or non-duality. (See “The Life and Teachings of Ramana Maharshi” by Jason Gregory in New Dawn 190.) These events defined the breadth of Brunton’s appeal, leading his readers, as he himself had been led, from psychism and mystical adventures to the supreme identity.

His subsequent books were a graded manual of training in what he simply called “philosophy,” from The Secret Path through The Quest of the Overself to the two-volume treatise The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga and The Wisdom of the Overself. He never sought disciples or led a movement in the outer world. His writings were a gift to the solitary seeker, who through circumstance or inclination lacks the support of a group or sect. But he accepted the burden of responding in person to sincere correspondents and giving his time and patience to countless private interviews.

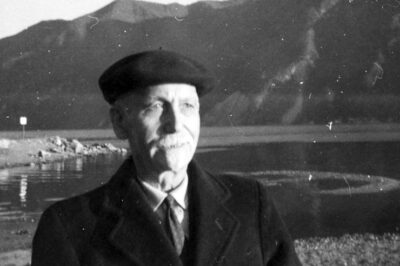

After his last book, The Spiritual Crisis of Man (1952), Brunton fell silent and apparently incommunicado. However, writing remained his daily habit. In his last decades, he wrote over 30,000 notes, ranging from one-liners to essays, in which he developed a universal philosophy for sane and spiritual living beyond anything in his books. During his last years, he allowed a few helpers to transcribe and classify them. They were published in 1984-89 as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, in sixteen volumes bound in the bright orange cloth of the Buddhist monk, then in paperback. In one of the later notes, Brunton muses on how in a future incarnation he will discover them and be delighted by something so congenial to his tastes.

He saw his mission, at least in one dimension, as making the wisdom and methods of the ancient East accessible to Westerners. The Theosophical Society, which he had joined in 1920, demonstrated the value of Eastern philosophies and the reality of occult phenomena, but had given little advice on how to apply them in one’s own life. This accounted for the success of magical and occult orders like the Golden Dawn, the A.M.O.R.C., or the Gruppo di Ur, which gave practical training or rituals, while also returning the West to its own esoteric heritage.

In preference to such groups, Brunton had the advantage of two outstanding personal guides. One was Allan Bennett (1872-1923), a former member of the Golden Dawn who had travelled to the East in the company of Aleister Crowley and remained there to become a Buddhist bhikku. As “Ananda Mettaya,” he returned to London on a mission to proclaim the Noble Eightfold Path, and Brunton acted for a time as his secretary. Brunton’s own work retained a certain Buddhist character, with its freedom from formalism and mere belief, and its confidence in the possibility of liberation from the ego. But Gautama’s view of all existence as suffering did not seem to him a useful principle for modern Westerners.

Brunton’s other mentor was an obscure character known only as “Brother M” or by his surname of Thurston. He was of partly Native American ancestry, settled in London and worked as a painter in the arts and crafts field. Before the First World War, he had led a group called “The Brothers,” and his few publications bear their imprint. In the 1920s, “M” served a small circle of spiritual seekers as a fatherly adviser and guide on the occult ventures in which they were involved. One of them recalled this period in an “occult autobiography” of 1927 (The White Brother by Michael Juste), in which the young Brunton appears semi-fictionalised as “David.”

There are mysteries about Brunton’s own biography, which he had no interest in revealing. To prevent misuse of his horoscope by inquisitive or hostile astrologers, he habitually gave out a false birthdate. When in 2019 his archive entered the library of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, some of these mysteries were resolved – evidently with his consent, for before his death he had carefully sifted his papers and destroyed many of them. We now know that he was born on October 21, 1898, and named Hyman Abraham Isaacs, the only child of a master bootmaker in East London. He attended the Central Foundation School, originally called the “Middle Class School,” founded for the sons of skilled workmen and tradesmen who, while not poor, could not afford schools like Westminster, Eton, St. Paul’s, etc. In April 1914, he was registered as a “Temporary Boy Clerk” in government employment and subsequently worked in the Patent Office.

At some point, the Isaacs adopted the surname Hurst, and Hyman the forename of Raphael. From 1917-18 he served in a tank regiment, perhaps chosen for his small stature to fit the cramped space in the vehicles. After the war, he ran a mail-order book service with his friend Michael Hurwitz (uncle of the eminent violinist Emanuel Hurwitz, writing as “Michael Juste” and bookselling as “Michael Houghton”), who established it as the Atlantis Bookshop, still flourishing near the British Museum. During the 1920s, Brunton worked for Foyle’s bookshop, in journalism, as personal assistant to a building contractor, and as author and editor, first of motivational and business publications, then as a prolific contributor to the Occult Review. By the end of the decade, Raphael Hurst was a familiar name in London’s esoteric subculture.

Membership of that world, then as now, spanned the social scale from the impoverished Bohemians depicted in The White Brother to the titled and celebrated. Brunton joined the Astrological Lodge of the Theosophical Society on the same day as Mrs Eugene Goossens, wife of the conductor Sir Eugene Goossens, and Lady Smith Dodsworth, a baronet’s wife. Thanks to such connections, he was enabled to study in the library of the Royal Asiatic Society and had propitious meetings with Sir Francis Younghusband, who had commanded the invasion of Tibet in 1904 and was now President of the Royal Geographical Society.

On the personal side, in 1922 Brunton married a young Danish woman, Karen Tottrup, and fathered one son, Kenneth Thurston Hurst. Within a few years, Karen and Kenneth moved into the household of Leonard Gill, proprietor of the Rudolf Steiner Bookshop, also near the British Museum. An amicable divorce followed in 1928, and as Kenneth matured, his father became his intimate friend and counsellor, steering him toward a successful publishing career in the USA. Kenneth’s memoir Paul Brunton: A Personal View remains the sole attempt at a book-length biography.

The first intention of Brunton’s Indian quest of 1930-31 was to meet Meher Baba. The silent Iranian was enjoying his first period of international celebrity, and the trip may have been financed by his English disciples. When A Search in Secret India appeared, with its foreword by Younghusband and its instant rise to the best-seller lists, they were sorely disappointed by the author’s verdict on their master. The contrast was all too obvious with the climactic episode of the book, the meeting with Sri Ramana Maharshi, whose reputation as an authentic jivan mukti (liberated in life) would draw many pilgrims to the holy mountain of Arunachala.

The tropical diseases which Brunton had caught in India affected him periodically for years. In order to recover and write his travelogue, he left London for Jordans, a Quaker village in Buckinghamshire where he had a cottage built and attended the venerable meeting house. Since 1932 he had been using “Paul Brunton” among his various noms-de-plume, and in 1935, with two books published under that name, he registered it formerly by deed poll. Later he always preferred to be addressed as “PB.”

Although he had grown away from the Theosophists, his second book again secured a stellar endorsement: the foreword was by Alice A. Bailey, the scribe of neo-Theosophical works ascribed to “The Tibetan.” The Secret Path was a practical manual on how and why to meditate, inspired by Indian practices but free from Sanskrit or other foreign terms. This would remain Brunton’s principle: to put everything into plain English, including some terminology of his own when necessary. Its crucial concepts are the Overself, World Mind, and Mind in Itself, whose equivalents can be found in esoteric religions and in higher philosophies such as Neoplatonism. Also essential to Brunton’s teaching of the path are the ascending hierarchy of Religion, Mysticism, and Philosophy; the Sage as the ultimate goal of human endeavour; and the central doctrine of Mentalism.

Brunton acknowledged that the mere observance of a religion, its morals, rituals, and beliefs, has its value for the majority of humankind. In a few, it kindles the aspiration for a personal experience of the Divine, a real encounter with one’s God. This leads to the higher degree of mysticism, with its special practices and great exemplars. But to realise the highest human potential, the mystic should not remain content with his or her experience, however sublime. The question of who or what is experiencing this must be asked, and there philosophy begins. Ramana Maharshi offered the exemplary practice of asking “Who (or What) Am I?”, whose answers become increasingly subtle, up to the sage’s state of absolute certainty where Overself and World Mind are one.

The philosophic ascent confirms the truth of Mentalism, using the term in opposition to materialism. While the latter takes matter as its first principle, mentalism holds that matter has no independent existence, but is an apparent form taken by mental processes, both individual and cosmic. Modern philosophers classify this as “subjective idealism,” but the fact of classifying it implies distance. To actively embrace the mentalist philosophy affects psychology, cosmology, theology, and even the physical sciences. These lose nothing of their practical value, but they deal with forms in the mind, not with a separate material reality. The true philosopher aspires to exclaim, with a legendary Hindu sage, “The world is just one’s thoughts!” Brunton predicted that the best Western thinkers would come round to the mentalist position by the end of the twentieth century. Perhaps they have, but where are they?

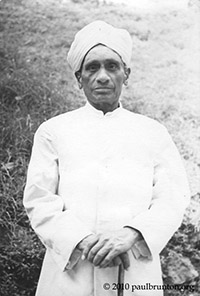

A second stay in India (1935-37) brought Brunton into contact and friendship with the Maharaja of Mysore via his court philosopher V. Subrahmanya Iyer, and Mussorie Shamsher, Prince of Nepal, who facilitated the retreat chronicled in A Hermit in the Himalayas. On the way back to England, Brunton gave interviews in Austria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, where a devoted group of students persisted throughout the Nazi and Communist periods. In August 1937, he accompanied Iyer to the International Conference on Philosophy in Paris, then to Switzerland for a meeting with Carl Gustav Jung, which resulted in Jung’s own Indian journey at the turn of the year.

With such high connections, one wonders why in 1938 Brunton obtained a PhD diploma from McKinley Roosevelt Graduate College in Chicago. This was not an accredited institution but a diploma mill that supplied impressive-looking documents for a fee. Brunton submitted a thesis that was the basis for his short book Indian Philosophy and Modern Culture. More worthy of the title was the magnum opus written during the early years of the war, published as The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga and The Wisdom of the Overself. The first volume reviews Brunton’s works to date and establishes the mentalist philosophy in a rather laborious way. The second takes flight, explaining how the universe comes into being, how individuals arise, what happens after death, the meaning of the current war, and ends with a series of practical exercises for turning this knowledge into realisation.

The Second World War found Brunton in India again, intending to stay for a few months first with Ramana Maharshi, then in Mysore. In fact, he was trapped there for seven years before he could obtain a passage back to Europe. The Maharaja gave him a home. The British authorities declined his call-up application and encouraged him to continue his work for the Allied cause. One can only imagine what sort of discreet diplomacy that entailed, travelling the length and breadth of the subcontinent.

Brunton’s future biographers will continue the story of the next 35 years, drawing on his archive to track him through America, England, Australia, New Zealand, and the European continent, to his last homes on the Swiss lakes. They will soon come across the name of Anthony Damiani, who met Brunton in New York in 1946 and founded Wisdom’s Goldenrod Philosophic Center, not far from Cornell University. From the late 1960s, Damiani led a small group in the study of Brunton’s philosophy, together with Neoplatonism, Buddhism, Vedanta, astrology, and, on the psychological level, Jung.

For those of Damiani’s students who visited Brunton in Switzerland, it was an unforgettable experience, as it had been for Brunton when he met Ramana, to be in the presence of a man who had fought the battle with the ego and won. That was the final invitation of his works: to overcome the obstacles to realisation of one’s true identity as the impersonal Overself and consequently as an unobstructed ray of the World Mind. In July 1977, Brunton spent a month at Wisdom’s Goldenrod, giving personal interviews, many of which are summarised in the Cornell archive. Two years later the Dalai Lama took time off his American tour to consecrate its new library building.

In his last years, Brunton found his routine of housework, shopping, cooking his vegan diet, attending to Swiss bureaucracy and a constant flood of correspondence increasingly burdensome. Various members of the philosophic centre went for weeks or months to help with his mundane affairs. After his death, following a second stroke, Kenneth Hurst gave his father’s literary estate to the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation. Work began immediately on producing the Notebooks, supported by Brunton’s Swedish publisher, and thereafter on sorting, scanning, and digitising his formidable archive. It took almost forty years before a suitable home could be found for it, when Cornell University’s library recognised, at the very least, a unique contribution to the modern history of India.

There are not many accessible archives of twentieth-century spiritual masters and none that can be studied in their entirety from anywhere in the world. Among the 87 file boxes are drafts of his books, unpublished essays, records of interviews, and the original “notes,” including those omitted from the published Notebooks, together with personal details that a more ego-identified person might have suppressed. Cuttings from newspapers and magazines range from metaphysics through the occult sciences to diet, health, and the conduct of life. Brunton paid close attention to world events, which he saw through the lens not of politics but of destiny and karma. A curious relic from the pre-xerox era is his well-worn travelling library, made by Indian assistants who typed out articles, extracts, and entire books. A collection of photographs records scenes in Egypt and India that no longer exist. There is a vast horde of letters in which readers and friends from every walk of life, from royalty downwards, bared their souls to him. Even more inspiring are his replies, for their ability to say exactly what the recipient needs to hear. Yet the older and wiser he became, the more he disowned the role of master or guru, describing himself as “a student of these matters.” To which one can only exclaim: “Some student! Some matters!”

Thanks and credit to the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation (www.paulbrunton.org) for the photos in this article and its digitisation of the archive at www.pbarchives.org, and to the Cornell University Library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, rmc.library.cornell.edu/EAD/htmldocs/RMM08692.html.

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton (sixteen independent but related volumes) are available from www.larsonpublications.com/shop/product-detail.php?id=19.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.