From New Dawn 207 (Nov-Dec 2024)

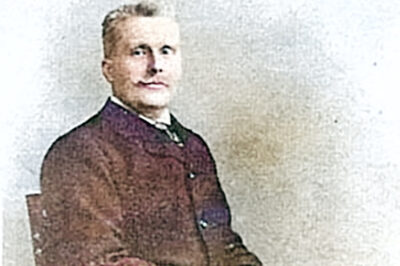

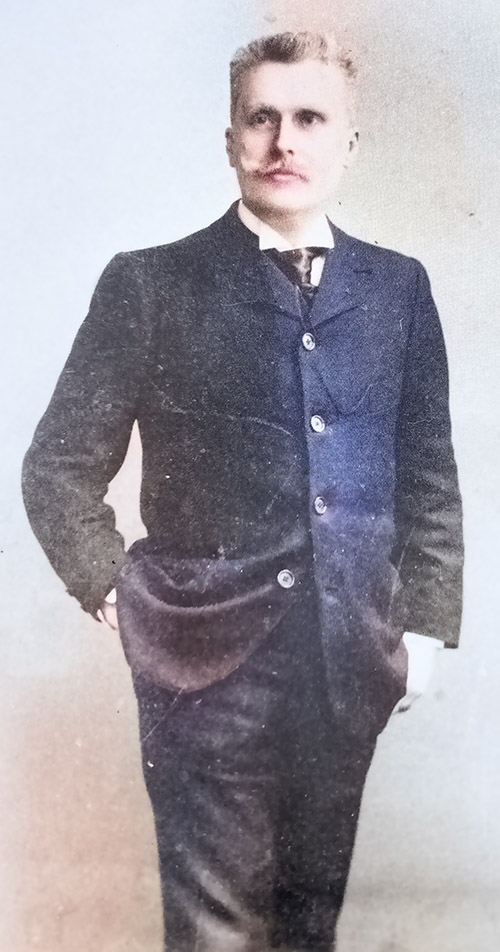

One could not wish for a better example of the Kshatriya or warrior path than Albert, Comte de Pouvourville (1861-1939). He was born an “army brat” in a minor aristocratic family, richer in honours than in land or wealth. They lived in Lorraine, facing the ever-present threat of German invasion. Albert’s childhood was overshadowed by the Franco-Prussian war and France’s humiliation (1870). As he recalls, he learnt to read from the daily orders of the imperial camp at Châlons, and shot at his first paper targets with General Saussier’s pistols. As the eldest son, there was no doubt he would follow the family’s patriotic path to revenge.

A different world opened to Albert at his high school in Nancy, where his classmates included Stanislas de Guaita, Maurice Barrès, and Paul Adam. They formed a clique of aesthetes and poets, all destined for literary or political fame. Albert’s best friend Guaita would become a pillar of the French occult revival; Barrès, a popular novelist and right-wing politician; Adam, an anarchist and leader of the Symbolist school of literature.

After this inspiring interlude, Albert attended the academy of Saint-Cyr, a breeding ground of France’s generals. He distinguished himself by all-round brilliance and absolute intolerance of authority. This persisted in his first military posting, where his father kept him from its worst consequences. Eventually, Albert took the historic leap of anarchic warriors and joined the French Foreign Legion.

Posting to Vietnam

He was posted to Indochina (then called Annam, now Vietnam), where the colonists held a fragile balance between European traders, mandarin and peasant classes, Chinese interference, brigands and pirates. Corruption and violence were the order of the day. Sickly horrors awaited those sent up-country to map the jungle and pacify its denizens. Thanks to his Saint-Cyr training, Albert had better surveying skills than anyone in the colony and used them to prepare the territory for roads, forts, and telegraph. During his first tour of duty, he collected enough material for three books describing his campaigns and criticising colonial policy. He was sure that he could have run things much better.

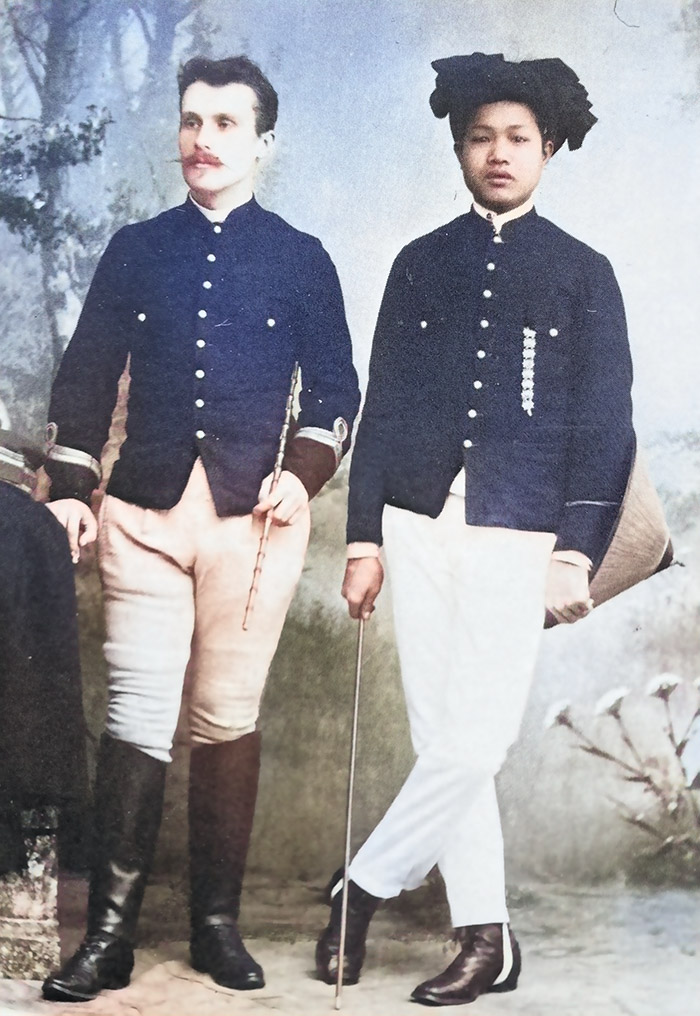

Arrogant he may have been, Albert had a natural sympathy with the Annamite people and respect for their ways. On his second tour of duty, he commanded a native militia corps and crushed a pirate gang that had massacred scores of civilians and soldiers alike. He writes impassively of scenes one would rather not read about. Always curious, he studied the Annamite executioner’s technique of striking between the cervical vertebrae and felt confident that he could do it if required.

He also made friends with a village chief and physician, who authorised his younger son Nguyen Van Cang to join the militia under Albert’s personal care. The document was written in classical Chinese with interpolations in Vietnamese script. Albert became competent, up to a point, in both languages. The Annamite chief instructed him in Daoist philosophy and, in some sense, initiated him into a secret society. What actually happened is obscure, the narratives mixing fact with fiction. But it sufficed for Albert to pass forever after as a Daoist initiate. He took the Chinese name of Matgioi, meaning “eye of day,” under which he published the relevant works, while Albert de Pouvourville continued his parallel career as novelist and colonial expert.

Matgioi’s third and final tour, ending in 1892, was more cultural than military. The resulting book on the arts and crafts of the region showed both an aesthete’s eye and a scientist’s attention to techniques and materials. It also contained the germ of the Traditionalist or “Perennialist” doctrine of art, as later preached by A. K. Coomaraswamy and Titus Burckhardt. This rejects the Western exaltation of the artist’s originality, style, and character in favour of the anonymous craftsman who aims for perfection in timeless forms endowed with spiritual symbolism.

Devotion to Opium

Matgioi’s time in Indochina, barely adding up to four years, yielded a mass of memoirs, novels, and cultural, geographical, and statistical studies. It also gave him a lifelong devotion to opium, on which he later ranked as a scientific expert. His nephew Guy de Pouvourville had childhood memories from the 1930s of his uncle’s extreme caution in admitting visitors and the odd smell permeating his house. Matgioi maintained that opium, properly prepared and used, protects one from most diseases and has no ill effects if kept within sensible limits: never more than fourteen pipes a day.

Another advantage of opium, in Matgioi’s scheme of things, is its anti-aphrodisiac effect. He approves of the Annamite attitude to sex as merely the means of propagating male descendants who will continue the cult of the Ancestors. Thus, “the man dispenses with the passionate longings, the time wasted in love, jealousy, and all the sentimentality in which, among the Whites, woman reigns exclusively.” There is no evidence that he had lovers of either sex. Later, he had a brief marriage which produced one daughter and a quick separation, and in his old age a second wife appears, of whom nothing further is known.

Occult Revival

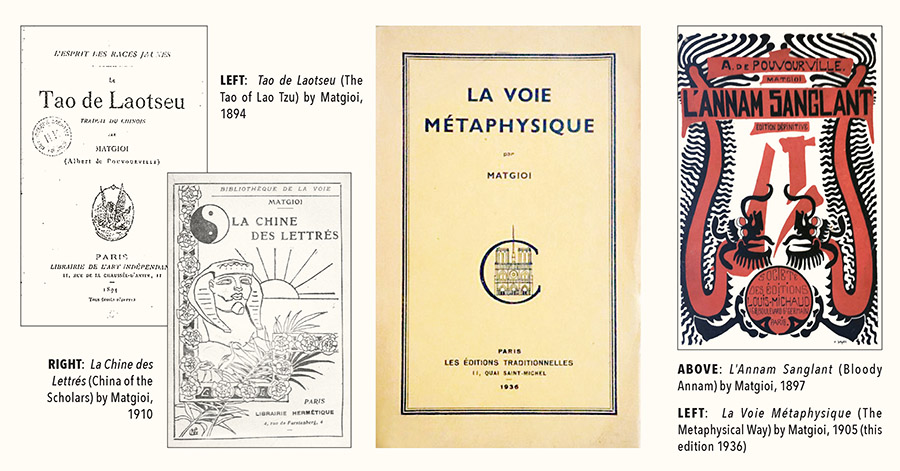

On his final return from Indochina in 1892, Matgioi found the French occult revival at its height and its informal centre at the bookshop of Edmond Bailly near the Paris Opera. There, one could meet alchemists and kabbalists, symbolist painters, decadent poets, and musicians such as Debussy and Satie. Bailly aimed higher than the popular psychic and spiritualist fads. His publisher’s emblem was a sinister-looking siren with the motto: “Not everyone’s kettle of fish” (Non hic piscis omnium). His journal, La Haute Science (The High Science), presented translations of esoteric classics of all nations and eras. This suited Matgioi’s taste, while his Daoist initiation gave him a unique flair. In 1894, Bailly’s journal published his translation of Laozi’s Daodejing (Tao Te Ching), which credited Nguyen Van Cang, the village chief’s son, as collaborator for the “paraphrase of the Chinese characters.” Matgioi included so many put-downs of previous translators that the editor felt obliged to apologise, saying that they weren’t in the spirit of the journal. According to modern experts, this so-called “exact translation” contains gross errors, and it certainly does not resemble the standard French or English versions. Nonetheless, it shows how the famous text was understood by some educated Annamites given to a Francophone public avid for Eastern wisdom.

Matgioi turned to Guaita’s friend Papus, the uncrowned despot of Parisian occultism, to publish his subsequent works: a series called “The Spirit of the Yellow Races.” This treated such themes as opium, Chinese medicine and poisons, popular ideas of the afterlife (mostly hellish), and Daoist secret societies. Meanwhile, “A. de Pouvourville” turned out novels and reportage set in Indochina. The most successful, Annam Sanglant (Bloody Annam), reached its 45th thousand by 1933. It is a superbly decadent work, glamorising the rebel as a superior and spiritual being, combining luscious description with gruesome violence, and promoting opium as the panacea for all ills.

Guaita’s death in 1897, aged only 36, was deeply felt by Matgioi and the whole esoteric community. The following year, Pouvourville put his rebellious past behind him and joined the French Colonial Institute, probably alongside secret work for the intelligence services. Given his family origin, he moved easily in establishment circles. There are hints of returns to Indochina and missions to North African colonies. Like Guaita, Pouvourville left no progeny, and whatever documents survived after WWII seem to be lost now.

Matgioi returned to the esoteric scene in 1904, directing his own journal, La Voie (i.e. “The Way” of Daoism). At last, he realised the project inspired by his Annamite master: “confronting the Truths of East and West with one another, which are really only one.” It would be a trilogy: La Voie Métaphysique (The Metaphysical Way, based on the Yijing), La Voie Rationnelle (The Rational Way, based on the Daodejing), and La Voie Social (The Social Way, based on Confucius). The first two were issued in monthly instalments, then as books in 1905 and 1907. The third volume never appeared.

Paris in the 1890s seethed with cults, conventicles, and tiny churches with huge claims. One of these, the Universal Gnostic Church, originated at a séance in 1889, on the instructions of the spirit of a medieval Cathar. Gnosticism claimed to be the true Christianity, distorted and persecuted by the Roman church. This suited the anticlerical Matgioi, who was consecrated as “Simon, Bishop of Tyre and the Orient.” Together with “Théophane, Bishop of Versailles,” he wrote a short doctrinal book called “The Secret Teachings of Gnosis” (Enseignements secrets de la Gnose). Like his Daoist work, it reframed traditional wisdom in modern terms. These included concepts such as Being and Non-Being, Universal Possibility, the nature of the Demiurge, the equivalence of death and birth, and the contrast of the Primordial Tradition with its distortions by “revealed” religions. All this offered “a practical doctrine, in the sense that it seeks to influence men and guide them, through multiple transformations, towards what it knows to be their final and excellent end.”

The Metaphysical Way & Yijing

Matgioi’s biography opens some revealing windows into his times, both in Indochina and Paris. His writings are another matter. Are they worth reading, much less translating? In the case of The Metaphysical Way, I have no hesitation. It is a forbidding title. But if one is looking for solutions to the enigma of life, as I was when I read it fifty years ago, it can be a landmark and even a lifeline.

My attention was first caught by mention of Matgioi in René Guénon’s Les États multiples de l’Être (The Multiple States of Being), which I was translating. La Voie Métaphysique was my first introduction to Daoism, apart from a friend who started each day by casting the I Ching, as it was known then. Matgioi’s approach could hardly have been more different. His interest is not in divination but in the Yijing as the earliest witness to the Primordial Tradition, as old as humanity.

According to Matgioi’s understanding of prehistory, which was derived from esoteric sources such as Fabre d’Olivet and Theosophy, humanity originated in central Asia. Climate change, or mere curiosity, caused it to descend to the plains, where it divided into the four races, distinguished by skin colour. Aeons later, the mythical Chinese emperor Fuxi (Fo-Hi) adapted the Tradition by giving it a geometrical expression. The straight line represents “active Perfection,” which in theistic terms is God’s own nature; the broken line, “passive Perfection,” which is the manifested universe. Their combination yields the system of the 64 hexagrams of the Yijing. None of this has anything to do with an anthropomorphic God but the impersonal process by which universes are governed. Here, I will summarise the conclusions to which his study of the Yijing and his Daoist initiation led him.

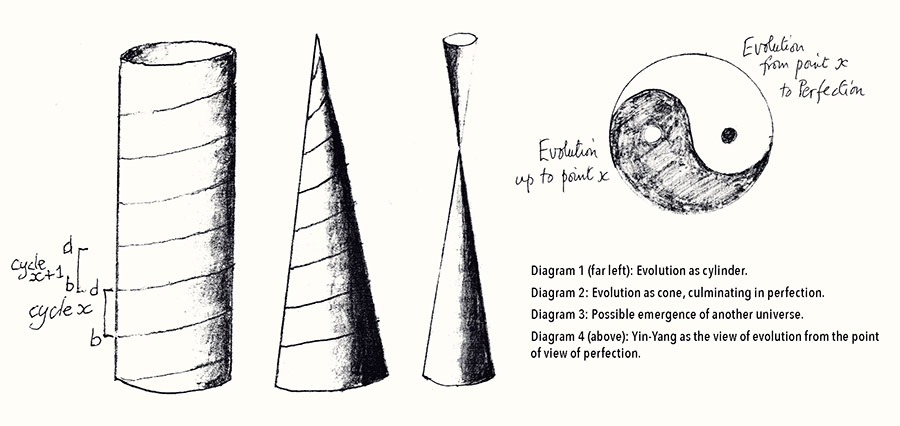

There is nothing special or privileged about Humanity. It is one of the universe’s innumerable forms, and earthly humanity is but one modification of that form. From our point of view, the human form is one of a multitude of others through which we pass. The process can be symbolised by a spiral inscribed on a cylinder (diagram 1). Each turn of the spiral represents one life, for example, that of an earthly man or woman. It begins with birth, which is, in fact, death to our previous and lower state (the preceding turn). It ends with death, which is birth into our next and higher state. The rising pitch of the spiral symbolises the Law of Harmony or “The Good,” which governs the evolutionary process on every scale – personal, collective, planetary, cosmic, and universal.

In geometry, a cylinder projected to mathematical infinity becomes a cone. This is the more appropriate symbol for the evolutionary process (diagram 2). At its vertex, in Daoist terms, is the Will of Heaven, which draws the universe to its ultimate Perfection and reabsorption. Matgioi leaves open the question of whether, once that is attained, another universe begins. If so, its symbol would be the double cone (diagram 3).

The Yin-Yang symbol (diagram 4) is like a slice through the evolutionary cylinder. It symbolises our present state, the dark half representing our emission from Perfection, the light half our future reintegration therein.

There is no freedom or chance in this grand process of universal evolution. Humans are not free to choose either their birth or death. But the human state is unique in one respect: between those limits, the Will of Heaven is not felt. Consequently, humans do have freedom, which they can use for better or worse. This alone is the locus of good and evil, along with their repercussions in this or a future life. Since evil does not exist as an independent entity, no punishment can be eternal. All beings are eventually destined for Perfection.

What joins our successive lives, these turns on the spiral of our evolution, is the Personality, a completely distinct entity. It is immortal, containing an indefinite number of individuals whose births and deaths do not affect it. It absorbs them all, the heritage of former cycles, and nothing of them is absolutely lost. All positive acts and emotions contribute to its ultimate goal of unity. This also ensures that personalities which were emotionally close will remain so in future cycles, as they were in past ones.

These metaphysical studies have a practical corollary. Our current state as humans gives us the freedom to conform to the Will of Heaven. If we rely on its principle, disengage from passions, and rationally weigh the consequences of each act, then every step we take – every effort, thought, even dream – is part of our inevitable spiral ascent to the Centre and the Truth.

One can see from this summary that Matgioi’s is an optimistic philosophy, in contrast to Traditionalists like Guénon who dwell with good reason on the negative aspects of humanity’s current state. Whereas they emphasise the devolutionary cycle of four Ages or Yugas, Matgioi takes the broader, evolutionary view, symbolised by the rising turns of the spiral. Each turn would then comprise an entire Yuga cycle, its components apparently declining as they accelerate, but each cycle being “higher” than the previous one. This would be the macrocosmic equivalent of the individual’s life, which is, in a sense, a decline from the Golden Age of infancy to debility and death, but for whom death to this state is immediate birth into a higher one. Incidentally, there is no support here for the Yuga theory invented for political purposes by Sri Yukteswar Giri (see my article “When Does the Kali Yuga End?” in New Dawn 138.)

Guénon & Matgioi

Having mentioned Guénon, I return to his role in Matgioi’s biography. In 1908, a group of Martinists held a séance in which the spirit of Jacques de Molay, last Grand Master of the Templars, manifested. He commanded that the Order of the Temple be renovated and headed by René Guénon. The young philosopher had already attracted attention by joining every possible esoteric, occultist, or Masonic group in Paris, and he consented – if, indeed, he did not precipitate the whole affair. The new Order’s first session of automatic writing produced a flood of information that included themes and even titles of Guénon’s future books, including The Multiple States of Being and The Symbolism of the Cross. The following year, the Gnostic Church, in which he was “Palingénius, Bishop of Alexandria,” started a monthly journal, La Gnose, under his direction. Just as La Voie had pre-published Matgioi’s books, so La Gnose served for Guénon’s. It also presented the Archéomètre, the great posthumous work of Saint-Yves d’Alveydre, and articles on Islamic esotericism by Ivan Aguéli, a Swedish painter who had been initiated in Egypt into a Sufi order. Matgioi contributed an article on “The Metaphysical Error of Sentimentally-Based Religions.”

Guénon, like Saint-Yves, claimed to have received teachings from mysterious Hindus. Together with Matgioi’s Daoism, Aguéli’s Sufism, and a Gnostic approach to Christianity, the foundations were being laid for a Traditionalist movement dedicated to the transcendent unity beyond the diversity of exoteric religions. Theosophy had been proclaiming this for thirty years, but the Theosophical Society was riven by squabbles and scandals following Blavatsky’s death. The new movement, which soon forgot its spooky origins, preferred to go straight to the ancient sources and the symbols of a primordial wisdom.

Matgioi later reflected on his Daoist initiation with a humility that other pretenders would do well to heed:

Beside certain incidental but still valuable notions, I mainly acquired the certitude of my imperfections, my ignorance, and my unworthiness. This, it seems, is the first step of wisdom. I greatly fear that I have not risen to others. But this poor ascent has nevertheless been extremely useful in my existence: it has given me defiance of the ego and disdain for the universe. (Chasseurs de Pirates! 1928, p. 185)

Matgioi’s Writings Post-WWI

The First World War effectively ended the French occult revival and with it Matgioi’s metaphysical works. He remained all the more active as a writer on colonial and military studies, beginning even in the heat of the war with close analyses of its progress. His fiction ranged from pirate and spy stories to prophetic visions of the next war. These were aimed at a popular audience and published in cheap “pulp novel” format.

By 1934, after the re-arming of Germany and the Nazi ascent to power, another war seemed inevitable. This time, it would not be fought by infantry in trenches but in the air, in tanks, and with unheard-of weapons that scientists, to their shame, were already inventing. This was the subject of his epic novel, published during 1934-35 under the authorship of “A. de Pouvourville, de l’Institut Colonial.” The first six parts were called La Guerre Prochaine (The Coming War), the following twenty-four parts L’Héroïque Aventure (The Heroic Adventure). It appeared in weekly instalments of 96 pages, promising “three hours of the most gripping reading.” The lurid covers and illustrations show ray guns, “navigyres,” “aquatanks,” “Z-rays,” and other fantasies of Art Deco science fiction. Germany is the eternal enemy; France the ultimate victor, allied with Mussolini’s Italy, Czechoslovakia and, in a minor role, Britain. A separate novel, Griffes Rouges sur l’Asie, depicts the coming Communist takeover of Asia, but Pourvourville’s future war, with a sad lack of foresight, takes place exclusively in the European theatre. It concludes with the upstart Chancellor “Heizler” crushed by a Berlin mob and a peace conference in Rome under the presidence of the Pope.

Was Matgioi, like that other warrior-author Ernst Jünger, turning Catholic in his old age? One wonders, for in 1934 he also published a book about Saint Theresa of the Child Jesus (1873-1897). Affectionately known as “The Little Flower,” Theresa represents an emotional Christianity for which Matgioi had always shown contempt. Guénon, when he heard about it, said that if Pouvourville was still alive, Matgioi was certainly dead! My interpretation is that with war clouds gathering, the ageing author felt a responsibility to his compatriots. His futurist epic warned readers of popular war stories, largely young and male, who would soon be on the front lines. The book on Theresa addresses devout Catholics in their own style, preparing them to face suffering with confidence in France’s protectors: Saints Genevieve, Clotilde, Joan of Arc, and Theresa. Now that the war has come and gone, those works are mainly of historical interest, while The Metaphysical Way, true to its subject, is a timeless contribution.

Thanks to Dr. Jean-Pierre Laurant, first authority on Matgioi, for his guidance in the world of Parisian esotericism and his indispensable work Matgioi, un aventurier taoiste (Paris: Dervy, 1982), and to Dr. Davide Marino for his later discoveries and friendly advice.

The author’s translation of Matgioi’s masterwork, The Primordial Tradition of Ancient China: The Esoteric Foundation of the I Ching and Chinese Cosmology, is published by Inner Traditions. Order your copy here.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.