From New Dawn 149 (Mar-Apr 2015)

On 13 December 1974, just over forty years ago, a 77-year-old Englishman died unexpectedly, after digging a flower garden, on the grounds of Sherborne House, an impressive mansion in the Cotswalds of England. Formerly a private school, it was now the headquarters of the International Academy for Continuous Education. For years he had made demands on himself that would have exhausted most people half his age within weeks.

A scientist by profession, he brought aspects of the experimental method to bear on spiritual technique and attempted a philosophical union of science and esotericism. He spoke many languages (eighteen, according to one count, including Italian, French, German, Russian, Turkish, modern and ancient Greek, Sanskrit, Pali, Persian and Indonesian) and had travelled widely, particularly in the Near East. His facility with languages allowed him access to Sufi teachers in a way that was difficult for Westerners of the period.

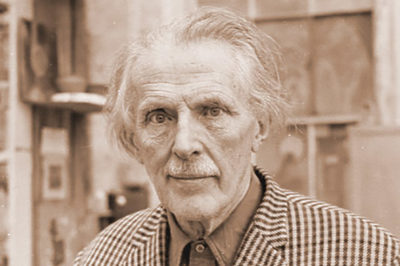

Several inches above six foot tall, with a distinctively English, slightly equine face, the stray wisps of white hair only marginally wilder than his eyes, dressed in tweed and checks and corduroys, in clashing shirts and woollen ties, John Godolphin Bennett was one of the great spiritual explorers of the twentieth century. Probably best known as a pupil of the spiritual teacher G.I. Gurdjieff, he was an extraordinary, if largely forgotten, teacher in his own right. In terms of energy and creativity, he was second to none. By his final years he had developed compassion and wisdom too.

Born in 1897 in Wimbledon to a middle class family, Bennett spent four years of his childhood in Italy, helping to lay the foundations of his linguistic ability. His father was a widely-travelled and rakish Englishman, his mother a puritanical, yet hardworking, American. Little is known publicly about his very early life. Bennett states in his autobiography Witness that his childhood seemed irrelevant in terms of the book as his boyhood was no different to any others.

Out-of-Body Experience

Bennett felt that in many ways his life truly began on 21 March 1918 when he was wounded by machine gun fire in the First World War on the western front. He woke up outside his body looking down on the beds of the army hospital. When he was taken to the operating theatre he heard medical staff commenting they would have to use coarse thread for his stitches as there was no fine thread left. After he had woken a nurse examining his stitches remarked they should have used fine thread, to which Bennett was able to explain there had been none left. The nurse was very surprised as there should have been no way that he would have known this as he had been in a coma for six days. This out-of-body near-death experience became a touchstone for Bennett’s understanding and he would later have similar experiences.

After the war Bennett undertook an intensive course in the Turkish language and was posted to Constantinople, where he held a sensitive position in Anglo-Turkish relations. Rapidly acquiring fluency in a very difficult language, he found himself being consulted as an expert in international diplomacy at a young age. He was able to visit dervish communities before the new Turkish government suppressed them. It was in 1920 and 1921 that he first made contact with G.I Gurdjieff and P.D. Ouspensky, each of whom had fled the Russian Revolution with both temporarily living in Constantinople. He had been impressed with some of the dervishes but found in the teachings of the Armenian Gurdjieff’s, also explicated by the Russian Ouspensky, a weight and clarity he had not experienced elsewhere. The Gurdjieff Work cannot be summarised in a couple of sentences but includes practices of self-observation, self-remembering, work with sensation, sacred movements and other exercises, supported by an extensive psychological system and a cosmology.

In 1923 he spent several weeks at Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at the Château Le Prieuré in Fontainebleau-Avon near Paris. Bennett is unusual in describing some of his many extraordinary inner and visionary experiences. Although there were expositions of Gurdjieff’s system and impromptu teaching by Gurdjieff, much of the time those at the Prieuré were involved in physical work, on various building projects or cleaning and cooking and other community needs.

Bennett suffered from dysentery but forced himself to work in the summer heat digging ditches for an irrigation system. Day after day Bennett willed himself out of bed when he should have been resting and threw himself into demanding physical labour. One day Gurdjieff put his pupils through a particularly arduous session of his movements or sacred dances after the day’s work. Bennett was one of the few who kept going through increasingly complicated exercises. He promised himself he would stop at the next break but became aware of Gurdjieff paying particular attention to him. He persevered and found himself filled with an energy so limitless that he went on to do another hour of intense digging which would have been far beyond his capacity had he been healthy. Gurdjieff later found Bennett working in the forest and told him that he had tapped into a great reservoir or accumulator of energy that few people were able to reach. Despite an offer by Gurdjieff to take him further into the teachings, Bennett left the Prieuré, feeling he had to attend to his own affairs first (and he was obviously physically exhausted). He would not see Gurdjieff again until 1948, 25 years later.

Bennett enthusiastically explored many spiritual teachings and followed a number of guides throughout his life, but it was the Gurdjieff Work he always returned to, and which most informed his own teachings.

After his political consultancy and intelligence work, Bennett was involved in a series of somewhat dodgy business enterprises, including an unsuccessful attempt to claim the inheritance of dispossessed Turkish nobles. This culminated in a period of imprisonment in a Greek jail until he was acquitted. Bennett found a more respectable career as a scientist in coal research, at the time the most important fuel source in the world. Although he attended a good school, Bennett never went to university and it is remarkable he could advance so much in mathematics, science and linguistics with little formal training.

He became part of Ouspensky’s groups in England, but had a chequered history with the brilliant, though somewhat authoritarian, Russian writer. Bennett hosted his own work groups which were acknowledged, if reluctantly, as being within Ouspensky’s orbit. In retrospect, Bennett seems not to have felt that he developed greatly during this period until he met Gurdjieff again in 1948. Ouspensky eventually banned Bennett from any contact with his groups on the basis of what seems to have been inaccurate gossip.

Bennett was never a stranger to spiritual effort and discipline, to a degree unimaginable to most of us. For instance, on 1 January 1931 he started a 1,000 day regime with the purpose of obtaining inner freedom. For most people, the regime would have lasted as long as a New Year’s resolution. Bennett kept it up but found himself strangely frustrated by the lack of genuine transformation. For a period of two or three years he practised the prayer of the heart, a technique central to Eastern Orthodox hesychasm, continually repeating the Lord’s Prayer internally between 300 to 1,000 times a day.

The return to Gurdjieff in Paris after the Second World War opened up an entirely new vista of spiritual techniques and teaching. Bennett’s diaries at the time have been published, along with his future wife’s, as Idiots in Paris (Samuel Weiser, 1991). They capture some of the contradictory aspects of his character, revealing the extraordinary efforts he made that were matched by similarly extraordinary states of consciousness. Yet they also paint a rather unpleasant picture of a man obsessed by his own salvation. He undoubtedly must have been very irritating at times. Later in his life he became considerably more understanding and compassionate.

Coombe Springs & Subud

In 1946 Bennett purchased a seven-acre estate at Coombe Springs in Surrey, England that developed into a community where people did practical work, movements and held meetings, with Bennett frequently demonstrating his brilliant lecturing ability. The first half of the 1950s saw Bennett travelling widely in Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Persia, and Iraq, meeting with various Sufis, many of whom struck him as very developed. In turn, he was often told by them that he had a major spiritual role to fulfil.

In 1956 Bennett was initiated into the latihan, the central technique of the Subud movement. This opened a flow of purifying energy described as a kind of instant mysticism but which was often accompanied in recipients by all sorts of spontaneous reactions, from bliss to horrifying emotional states and violent thrashing about. Bennett experienced what he described as a purgatorial state of conscience, vividly perceiving the affect he had on others, his many affairs with women, his fear of women, his unreliability and untruthfulness, his insensitivity, self-will, and on and on for a whole fortnight.

Bennett had a naturally remarkable intellect that he developed through hard work, and he had trained his body to be strong and resilient. Yet he felt it had taken Subud to finally open his heart. He put aside the disciplines of the Gurdjieff Work, which seemed unnecessary in comparison to the efficacy of the latihan, and turned Coombe Springs over to the promotion of Subud, becoming a somewhat messianic spokesperson for the movement, which attracted much media attention.

His enthusiasm for Subud eventually waned and by the early 1960s Bennett had once again performed an about turn, resumed Gurdjieff-style exercises and experimentation, and started work with a young group of brilliant scientific men on the final two volumes of The Dramatic Universe.

The Dramatic Universe

His magnum opus, The Dramatic Universe, was published in four volumes between 1956 and 1966, but Bennett had been working on the material for it since the 1940s. Bennett intended it as a synthesis of what he termed fact and value: fact being the province of science and value that of religion, philosophy, and esotericism. The Dramatic Universe is a work of serious philosophy by a genuine scientist who is the master of his materials, based on the principles of esoteric spirituality that he practised in his daily life. It is full of insights and extraordinary viewpoints. It is also very difficult reading. A selection of chapter titles from the first volume illustrate the difficulty: “The Existential Tract and the Cosmodesic,” “Pencils of Skew-Parallels,” “The Higher Gradations of Thinghood,” “Quinquepotence–Viruses” not to forget “Septempotence–Organism,” and so on.

The combination of esoteric teaching, formal philosophical language and scientific rigour constituted a recipe for being ignored, and the proof is in the pudding. Few Gurdjieffans, and even many of those involved in the Gurdjieff-Bennett Work, let alone the general public, have read the entire Dramatic Universe (and I have to include myself in this category.) It is, however, a mine of possibilities where gems await determined diggers.

The discipline of systematics is foundational to The Dramatic Universe. This is a method developed by Bennett of using number to describe “systems” and their progression. Gurdjieff’s Law of Three and Law of Seven offer important ways of understanding the Universe on all scales. The Law of Three describes how a triad of forces is necessary for every phenomenon to occur, while the Law of Seven, or law of octaves, using the musical scale, describes how any process changes through time and requires help from outside at certain places, known as intervals, to keep progressing in the original direction.

Bennett saw that it was arbitrary to limit discussion to only these numbers and incorporated Gurdjieff’s laws of three and seven into the general scheme. A system with a single term has a unity in which there can be no development. Two-term systems are usually polar, containing opposition. When there are three terms, a system largely matches Gurdjieff’s triads with their active, passive and neutralising forces. Four term systems form a tetrad that has stability. These number systems use the natural properties of whole numbers. Different number-systems have different properties that seem contradictory but may be integrated into a grand scheme.

As a tool of analysis, systematics allows the user to examine the elements of a situation and understand the relationships between them. As an esoteric technique, it also has the potential of explicating elements of sacred geometry and Pythagorean numerology. The application of systematics has gone beyond esotericism to management and industry.

Spiritual Smorgasbord

Just as his adoption of Subud had alienated a large number of people who practised the Gurdjieff Work, Bennett’s return to the latter alienated those who had become Subud enthusiasts. Never one to allow his spiritual smorgasbord to get too stodgy or lack variety, in the 1960s Bennett visited a Nepalese teacher named Shivapuri Baba and converted to the Roman Catholic faith. Bennett had had visions of Christ at various times in his life. He also held a correspondence with leading physicist David Bohm, who would later work with Krishnamurti.

To cap it all, Bennett was approached by Idries Shah, the Western populariser of Sufism. Shah presented himself as a living representative of the same esoteric source as Gurdjieff. He persuaded Bennett to hand over Coombe Springs entirely to his own work, including the deeds of the property, with no conditions. Bennett and his close followers were eventually forbidden to enter the property and it was sold off for a considerable price. This event is a litmus test for one’s attitude to Bennett. Many see Shah as perpetrating a dishonest scam which the naive Bennett fell for. Yet Bennett seems to have been genuinely liberated by the experience and felt that Shah had given him the opportunity of moving forward.

In 1969 Bennett had another near-death experience due to uric acid poisoning, during which for around 20 hours he was close to death or permanent brain damage. He experienced a continual joyful awareness which convinced him that he could survive both the loss of his body and mind yet retain a self. He mentions other out-of-body states, including one when he was reading for Gurdjieff in Paris, for which Gurdjieff scolded him and told him if he hadn’t been there Bennett might not have got back into his body.

Academy for Continuous Education

In 1971 he began the final phase of his life, setting up the Academy for Continuous Education at Sherborne House in the Cotswolds. Five experimental courses each of ten months duration were hosted at Sherborne House. These were mostly attended by people in their twenties, a large proportion of them American. (Bennett had attended the Isle of Wight Festival and was impressed by the energy of the counterculture.) The courses attempted to give a taste of the spiritual life and work on oneself to help orient people for the rest of their lives. True to form, other teachers visited the academy including Hasan Shushud, a Sufi, and Bhante, a Cambodian monk, who taught a form of meditation based on colour using coloured crepe paper and a lightbulb. Around 500 people experienced the courses over a period of five years, Bennett dying near the beginning of the fourth course. The teaching was founded on Bennett’s development of the Gurdjieff Work, including movements and work on sensation, as well as all sorts of techniques from the Sufi zikr repetition and latifa work (somewhat similar to chakras), to meditation and that old standby of digging the garden.

Critics see Bennett as a butterfly, abandoning the Gurdjieff Work for Subud, Subud for Catholicism and Shivapuri Baba, then submitting Idries Shah, and so on, with dashes of contact with traditional Sufis drizzled regularly over the stew. At times it seemed a crazy pebbledash of mixed teachings. Those broadly sympathetic to Bennett – and I am one – may see these rather as correctives to the limitations of each tradition or influence. The instant mysticism of the latihan compensated for the exceedingly hard-won fruits of the Gurdjieff Work. The Sufis offered a connection to an ancient but living tradition that was most likely one of Gurdjieff’s sources. When Bennett became a Catholic it was likely he filled a gap in his overall spiritual and emotional make up, one that his native Anglicanism did not fill.

Although The Dramatic Universe is a notably indigestible read, the dozens of other works published in Bennett’s name are quite approachable, even easy reading. Many of these are based on transcriptions of talks to his pupils. Audio recordings show his delivery to have been slow and measured, delivered in a melodious piping tenor in a particularly refined English accent. Deeper Man (Bennett Books, 1995) is perhaps a good place to begin, informally yet systematically laying out much of Bennett’s own teaching, drawing on Gurdjieff, Sufism and other sources, yet very much Bennett’s own.

Bennett’s legacy perseveres in a variety of groups and individuals. Claymont Court in West Virginia, USA, purchased shortly before Bennett died, remains open as a centre for spiritual activity. George and Ben Bennett, J.G.’s sons, continue the Gurdjieff-Bennett work, now under the umbrella of the J.G. Bennett Foundation (www.jgbennett.org), holding occasional extended practical courses. They and other pupils of Bennett and those interested in his work meet for various international gatherings, which manage to bring together the various strands of Bennett’s heritage.

Anthony Blake has held the flame of Bennett’s experimental approach and his principle of integration without rejection and gone on to develop several techniques in partnership with a variety of other seekers. Robert Fripp, guitarist and leader of the progressive rock band King Crimson, attended the final Sherborne course, the first after Bennett died, and went on to develop Guitar Craft, which uses guitar playing as a vehicle for development. Yet outside these small circles Bennett’s legacy waits to be rediscovered.

Meals in Bennett’s groups at Coombe Springs and Sherborne were typically consumed in silence, but they began with a grace composed by Bennett that could serve comfortably as an epitaph:

All Life is One, and everything that lives is holy.

Plants, animals, and men, all must eat to live and nourish one another.

We bless the lives which have died to give us our food.

Let us eat consciously,

Resolving by our work to pay the debt of our existence.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.