From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 10 No 3 (June 2016)

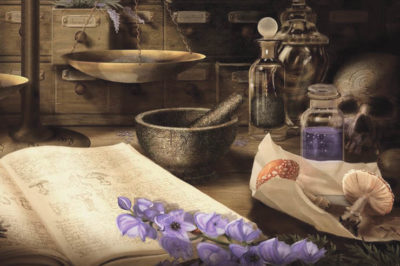

When I first started my investigation into the so-called “witches’ ointment” of the early modern period I was looking for a specific kind of ointment that caused a specific kind of experience – a “flying” experience, as recognised in contemporary popular culture.

But to delve deeper into the trial records, popular sermons, demonology texts, and medieval pharmacy one will discover not just a flying ointment, but a host of uses for these ointments. Therefore, a more neutral term, like “psyche-magical” (psychedelic + magical) is useful to convey the breadth of experiences available through these concoctions.

Such magical drug practices (veneficia) included (but were certainly not limited to) entheogenic uses (“generating the divine within”), bewitchment, prophecy, Christo-pagan medical magic, transformations, recreation, and, of course, flying. In short, to address only “flying ointments” in early modern Europe would be akin to referring to all cars in Australia as “Hondas.” Medieval veneficia was just as various as the cars we see on the roads every day. In point of fact, people didn’t even use just ointments: they also employed powerful potions, powders, and fumigations as drug delivery vectors.

To be sure, people did use these ointments as flying ointments. However, a further breakdown of even the flying ointment is possible. There is strong evidence to suggest that some magical practitioners used these flying ointments in ways that had nothing to do with entheogenic experiences and also in ways that had everything to do with entheogenic experiences! In still other cases, these magical ointments were used entheogenically that had nothing to do with flying. For example, while Dominican theologian Johannes Nider (c. 1375–1438) described a flying ointment used for entheogenic purposes, we must mark that against a report from Abraham of Worms (c. early to mid-15th century) who tells of a Linzian witch who used her flying ointment as a way to astral project leagues away to Abraham’s home town. There is not a trace of entheogenism in Abraham’s chronicle of the event. As further evidence that mindset and drug-use went hand in hand, it is perhaps no surprise that Nider’s description of a witch using an entheogenic flying salve included magical songs and chants, while Abraham’s report of a non-entheogenic use included no magical accoutrements beyond the powerful ointment itself.

Moreover, entheogenic experiences didn’t just take the form of spiritual flying; in some instances, according to tales from Northern Germany, a salve was rubbed near the eyes to allow a person to see the “inhabitants of the lower world.”

Beyond the entheogenic practices of common people, Renaissance magicians would fumigate powerful solanaceous psychoactives like henbane and mandrake to produce visions of spirits. Such plants, we are told, were even called “spirits’ herbs,” by magicians – a testament to these substances as used as entheogens in even high culture. On other occasions necromancers, too, would prepare henbane fumigations to call upon the dead. One further case featured a man who inhaled a psychoactive powder so that his “evil spirit” would appear to him. This is not to suggest that only solanaceous plants were used as entheogens.

There is evidence of a remote bacchanalian kind of heresy in the Cottian Alps that survived into the High Middle Ages, which employed the poisons from toads in their Eucharist. The mixer of the potion, one Bilia la Castagna, would brew her potion on the eve of Epiphany, perhaps suggesting that the drink was meant to induce visions of Christ. The report of Bilia’s brew is invaluable to historians because it describes the toad potion in a way consistent with bufotenine (the active psychoactive in such toads): one man drank too much and almost died; the other congregants who drank a smaller amount revelled in their visions.

Here we can see clearly the range of spiritual uses and beliefs associated with the entheogenic state, as spiritual flying ointments, as fumigations for inviting spirits into one’s home, as snuffs, as non-flying entheogens, and as Eucharists mixed by some heretics for their ceremonies.

Beyond the realm of entheogens, the ointments (and potions, powders, and fumigations) were utilised for other forms of medieval psyche-magic as well. For example, a certain kind of mercenary sorcery (“bewitching”), found in both common sorcery and learned magic, might include the surreptitious drugging of a rival or nagging neighbour. To begin in the realm of “low” or “common” sorcery, the spell-caster might place a drug in someone’s food or drink. Then, waiting for the opportune moment for the drug to take effect, she or he would then chant incantations at their victims – the victims, believing that the true power came from the spell-caster, not the drug. Other times, elaborate magical rituals covered the use of the drug, as we see with the dealings of a physician-magician from Gelders. After performing extravagant rituals, he slipped an unfortunate woman a drug, despicably raping her as soon as she fell under its spell.

Sadly for those living at the time, some trickery didn’t involve grand magical demonstrations at all, but rather relied on only two things: the drug itself, and the gullibility of the victim. For example, Dutch physician Petrus Forestus (1521–1597) warned that charlatans, posing as dentists, would often have an ailing patient inhale the fumes of burning henbane. As the drug took effect, and the victim started to fall into a soporific stupor, the thief would fleece the prey of her or his possessions, taking off shortly thereafter. This seems to have been a common form of thievery in the early modern period.

But not all non-flying magical drug practices were so dastardly. Some were benevolent, as found in some of the Christo-pagan shamanistic medical magic (yes, that existed!) of the time. Indeed, one of the more interesting realms of this psyche-magic could be found in the private homes of an ailing villager who, unable to afford a university physician, would call upon a local healer instead. What makes this form of shamanistic medicine so unique from other practices in the worldwide entheogenic geography is that it seems it was up to the patient to ingest the drugs, not the healer. Such magical medicinal ceremonies were instrumental in protecting against supernatural disease-makers like elves and goblins. It included the patient taking the powerful hallucinogen henbane, while the healer sung chants over her or his body. It is difficult to imagine the patient not having some supernatural, otherworldly experience with these kinds of stimuli in place.

Like today, these drugs also had purely recreational uses – a paradigm that goes at least as far back into history as the Old Testament (Genesis 30:14). The word found in both legal and ecclesiastical writing is pocula amatoria, which translates literally into “love cup.” These love cups, of course, weren’t always cups (i.e., potions), but took the form of ointments and powders as well. The most (in)famous additive to these love philters was hallucinogen mandrake. Though, that is not to say that other intoxicants like cannabis, henbane, and opium weren’t also utilised. It’s really anyone’s guess, as the most common description of the ingredients in love potions only mention a venene, a “drug.” The drug was probably different from the ones found in flying ointments, as the point of a love drug wasn’t to fall into a surrealistic dream world, but rather stay awake and vibrant! Thus, drugs like mandrake were used for both lust, and anti-lust purposes, again indicating that the power of the user’s mind was sometimes (though certainly not all times!) enough to sway the magical experience one way or the other.

But this also depended on who was using the drug. In fact, in a move that turns this entire genus on its head, the same drugs were also used to alleviate sexual tensions! Two authors, Petrus Hispanus and the famous Hildegard of Bingen saw these psychoactives as a way to halt promiscuity in men (turns out, it would take more than magic to cure that!). But their records are important as they show a variety of psyche-magical uses of these drugs. In fact, Hildegard names mandrake specifically in her writings. Only she didn’t think that it served best as a sex promoter, but rather a sex inhibitor, a paradigm that some, like famous Renaissance magician Heinrich Cornelius von Nettesheim, clearly ignored. In fact, the Renaissance magus sung the praises of mandrake as the earlier pagans had: it allowed a person to achieve multiple orgasms! Others, like Cristóbal di Acosta favoured opium as the preferred drug of sexual pleasure, remarking that only stupid people should use it as it sent the imagination on fire! Intelligent and imaginative people, on the other hand, would orgasm too quickly if they took opium and therefore should avoid it.

Evidence suggests that some practitioners used these ointments for certain types of animal transformations. What that means, or why it was a part of the magical landscape, remains unknown. It has been suggested this has some shamanistic undertones, but the truth is that not every kind of animal transformation had anything to do with shamanism. Other times, perhaps it did; it is really difficult to tell sometimes. Take Finicella, a sorceress who lived in Rome during the early 1400s. A popular preacher named Bernardino of Siena railed against Finicella, not just because of her magical practices, but also that she used a hallucinogenic ointment to imagine that she turned into a cat. While such transformations can be associated with shamanistic endeavours, we really cannot say one way or the other why Finicella used powerful drugs in such a way. Perhaps it was a form of entertainment before movies, radio, and television? In any event, this act of animal transformation was a popular use of magic by at least the mid-16th century. In fact, there are reports from both medical students of the time and common sorceresses using these drugs to imagine they were everything from geese to cows. In this latter example (turning into a cow) a young German girl named Magdalena attempted this magic and also believed that the ointment she used would also allow her to fly to a “witch dance.” Magdalena burned for persuading others to try it: a friend of hers, instead of turning into a cow and flying, experienced a “bummer,” being driven out of her senses.

Unfortunately, not a single record details why this kind of animal transformation would be a preferable use of intoxicants. Perhaps it was some kind of fertility rite, the animals representing hopeful abundance in the future? This is, of course, mere speculation. All we can say is that this kind of magic apparently was desirable for some individuals.

While the early modern “witches’ ointment” was surely invented by zealous theologians in the early 1400s as an explanation for the perceived “flight” of entheogenic fertility practices, the magical landscape ran much deeper than just a flying ointment. There were instead a host of ointments, powders, potions, and fumigations used for every kind of magical practice of which we are aware. So while the early modern flying ointment did exist, it is only the surface of a deeper reservoir of drug magical practices. Other kinds of magic, whether transformative, medicinal, mercenary, or otherwise, employed many of the same drugs found in flying ointments. However, the mindset of the person experiencing the effects of these kinds of drugs seems to have made a noticeable difference in how and why these kinds of psyche-magical substances would be interpreted.

For more on the above, read Thomas Hatsis’s book The Witches’ Ointment: The Secret History of Psychedelic Magic.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.