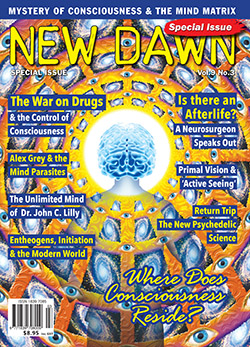

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 9 No 3 (June 2015)

It is almost impossible for modern man to understand how he can be ‘blind’. We see what is in front of our noses, and we could not see more even if we opened our eyes as far as they will go.

But there is another kind of blindness, which American philosopher and psychologist William James describes in his essay ‘On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings’. James recounts how he was being driven, in a buggy, through the mountains of North Carolina, and looking with revulsion at the newly-cultivated patches of land (called coves) and reflecting how ugly they were. He asked the driver what kind of people lived here, and the driver replied cheerfully: “We ain’t happy unless we’re getting one of these coves under cultivation.” And James suddenly woke up to the fact that these homesteaders regarded each cove as a personal victory, and saw it as beautiful.

We become blind to things by imposing our concepts on them and looking at them with a kind of indifference, which arises from our conviction that we know what they are already. James was quite sure that the coves were ugly, without seeing that the ugliness lay in his own eyes.

But even when we know this, it is still very difficult for us to grasp just how the ancient Egyptians – or our Cro-Magnon ancestors – somehow saw the world quite differently, and might consequently have developed their own ‘high levels of science’. The following example should make it clearer.

One of the few men to whom this ‘ancient seeing’ came quite naturally was the German poet [Johann Wolfgang von] Goethe. And Goethe’s vision of science can enable us to grasp what it is all about.

It would simplify what follows if I explain how I happened to stumble on Goethe’s vision of science.

I had been an admirer of his work ever since my teens, when I first read Faust in the old Everyman edition. His vision of a scholar rendered miserable by his sense of the meaninglessness of life struck a deep chord with me at the age of sixteen. Good English translations of his work are rare, but over the years, I went on to collect every volume I could lay my hands on.

A few years ago, I came across a translation of Goethe’s Theory of Colour, but was of two minds whether to buy it. I knew Goethe was an enthusiastic amateur scientist, but felt that basically he was no more than that – an amateur. All the same, I bought the book – and it stayed unread on my shelf.

I should have been aware of the risk of dismissing any aspect of Goethe. For example, I knew that he had finally been proved correct about the intermaxillary bone. This is a bone in the upper jaw that holds the incisors, and all animals possess it. But in the 1780s, a famous Dutch anatomist named Peter Camper announced that what makes man quite unique is that he has no intermaxillary bone in his jaw. And Goethe, who was an evolutionist long before Darwin or Lamarck, was sure this had to be nonsense. So he proceeded to search through piles of animal and human skulls, and found signs of the intermaxillary bone in man, although it was now little more than a seam uniting the halves. But when he announced this to Camper and other scientists, they dismissed him as an amateur. By the time of Darwin, Goethe was recognised to be right, and Camper wrong.

However, where colour was concerned, I simply could not see how Goethe could question the accepted theory. We were all taught at school that white light actually consists of the seven colours of the rainbow – red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. And Newton proved this by a simple experiment. He made a small hole in his blind, to admit a narrow beam of light, and then passed this through a prism. And the light split into the seven colours. Surely that is quite conclusive?

Goethe borrowed a prism and set about repeating Newton’s experiment. And he immediately came upon an anomaly. If he looked at a white tabletop through the prism, it did not turn into a rainbow-coloured table. It stayed white, and the only rainbow colours were around its edges. And this proved to be generally true. Colours only appeared when there was one kind of boundary or edge.

Goethe took a sheet of paper in which the top half was white and the bottom half black. When he looked through a prism at the halfway line, he saw that the colours red, orange and yellow run up into the white half. But when he stared intently at the black boundary, he saw that the darker colours of the spectrum are there – light blue closest to the boundary, then dark blue (indigo) and violet. So the order of the colours does not run in the proper rainbow sequence: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet, but yellow, orange, red, blue, indigo, violet, apparently defying Newton’s law.

All this led Goethe to what will seem to us a strange conclusion. If you look at the sky on a hot day, it is deep blue overhead, and becomes lighter as your gaze travels towards the horizon, where the atmosphere – loaded with light – is thicker. But if you could travel upwards in a rocket, the sky would become steadily bluer and darker until it turned into the blackness of space.

On the other hand, when the sun is directly overhead, it is yellow. As it moves down to the horizon, its light turns to red. So where the sun’s light is concerned, the atmosphere produces the three light colours, yellow, orange and red. Where darkness is concerned (outer space), the atmosphere creates the three dark colours, blue, indigo and violet.

To express this crudely, Goethe is suggesting that the dark colours – blue, indigo, violet – are made by diluting blackness, while the light colours – yellow, orange, red – are made by thickening the light.

My own reaction, when I read all this, was a desire to tear my hair and throw the book out of the window. Where, I wanted to know, was Goethe’s theory superior to Newton’s? And anyway, what did it matter?

At that point, my friend Eddie Campbell lent me a copy of The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way of Science by Henri Bortoft, a scientist who had been a pupil of the physicist David Bohm. It looked so difficult that I decided it would take years to read, and I had better buy my own copy – which I then allowed to sit on my shelf for over a year. But when I finally came to read it, I realised that it is among the most important books I had ever bought.

Bortoft’s book offered some interesting new facts. To begin with, when Goethe had been observing the colours, he would close his eyes, and envisage what he had just seen. He would try to see the colours, in their right order, inside his head, and would do this until he could conjure it up with as much reality as the actual colours.

He was practising what I described as ‘eidetic vision’. (German philosopher Edmund Husserl, who established the school of phenomenology, introduced the term ‘eidetic vision’ to describe the ability to observe without “prior beliefs and interpretations” influencing understanding and perception.)

For what purpose? Let Bortoft explain:

“When observing the phenomenon of colour in Goethe’s way it is necessary to be more active in seeing than we are usually. The term ‘observation’ is in some ways too passive. We tend to think of an observation as just a matter of opening our eyes in front of the phenomenon… Observing the phenomenon in Goethe’s way requires us to look as if the direction of seeing were reversed, going from ourselves towards the phenomenon instead of vice versa. This is done by putting attention into seeing, so that we really do see what we are seeing instead of just having a visual impression. It is as if we plunged into seeing. In this way we can begin to experience the quality of the colours.”

And after describing Goethe’s way of re-creating the colours in his imagination, Bortoft explains:

“The purpose is to develop an organ of perception which can deepen our contact with the phenomenon…”

Goethe called this “active seeing.”

And this, I would suggest, is the difference between modern man and ancient man. Ancient man, because of his closer contact with nature, was far more accustomed to active seeing.

I happened to be sitting in bed at about 6.30 on a bright summer morning as I read Bortoft on Goethe. Suddenly I understood what he meant. I looked out of my window at the garden, with its trees and shrubs, and deliberately did what Goethe recommends: that is, I tried to see it actively.

This made me aware that when I normally look out at the garden, I am seeing it passively, taking it for granted, feeling I know every inch of it. Instead I tried to suspend all ideas, all preconceptions, and simply to look as if it was somebody else’s garden and I was seeing it for the first time. The immediate effect was a feeling of being drawn into nature. The grass, the trees, the shrubs, suddenly seemed more real and alive. Moreover, they seemed to be communicating with me. There was an odd sense of being among old friends, as if I belonged to a club in which I felt perfectly at home.

I also realised that Goethe, like many poets, possessed this kind of perception naturally. In Faust he talks about nature as “God’s living garment.” In his lyric poetry there is a tremendous, surging vitality that reminds me of certain of Van Gogh’s later paintings – ‘The Road With Cypresses’ and ‘The Starry Night’ – in which the trees seemed to have turned into green flames roaring upwards towards the sky.

There is a well-known story about how Goethe and the poet Schiller left a rather dull scientific lecture in Jena, and Goethe remarked that there ought to be some other way of presenting nature – not in bits and pieces, but as a living actuality, striving from the whole to the parts. And Schiller shrugged and remarked: “Oh, that’s just an idea.”

But he was wrong. For Goethe it was not just an idea; it was something he saw when he looked at trees and flowers and grass. They looked alive, as if nature was, in some way, a single organism.

As an exercise, try looking at a garden with ‘active seeing’. Instead of seeing it as a kind of still life, like a painting, make an effort to recognise that it is in continual motion – very slow motion, but motion nevertheless – and that plants are as alive as insects or birds or bees.

No doubt this was not true all the time; like the rest of us, Goethe must have had his periods of fatigue in which he saw things mechanically. But in his wide awake moments, he seems to have seen nature as Van Gogh painted it.

And, as Bortoft recognised, this is not just a matter of making more effort. It is a matter of developing an organ of perception.

William Blake said: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite.” Aldous Huxley quoted it in his book The Doors of Perception, in which he recorded his experiences with the psychedelic drug mescalin, during which everything suddenly appeared far more real. This is clearly the kind of thing Bortoft is talking about.

This ‘organ’ is what the German writer Gottfried Benn called “primal vision.”

How did we lose it? By developing a kind of mechanical perception to cope with the complications of our crowded lives. Wordsworth understood all about it, as he shows in the ‘Intimations of Immortality’ ode. For a child everything seems new and exciting, “the glory and the freshness of a dream.” This is because he lives in the present, and everything appears sharp and clear. Then “shades of the prison house begin to close” upon the growing youth, as life becomes more difficult and demanding. And by the time he reaches adulthood, he is always in a hurry, and the “glory” has faded into the light of common day.

All that this means, of course, is that he no longer puts the effort into seeing things. When a child sits in front of his favourite television programme, he turns his full attention on it – so much so that he often fails to hear when you speak to him. And everyone can remember that delightful feeling of listening to the rain pattering on the windows – one girl I knew told me she used to roll herself into a ball and say: “Isn’t it nice to be me?” And indeed, it is nice to be you – provided you turn your full attention on it, and don’t permit any ‘leakage’. But this is precisely what we do as we grow up – we spread our attention too thin, and then accept that diluted version of reality as the real thing. And so the ‘certain blindness’ sets in.

Animals don’t do that. They live comfortably in the present, and turn their total attention to anything that interests them. We ‘civilised’ humans have forgotten how to do this. And we are not even aware we are short-changing ourselves, because we think this is the way things are.

One of the worst effects of this diluted and degraded consciousness is that it fills us with stress, and causes us to direct attention at worries that don’t deserve it. And when we occasionally experience a breath of real consciousness – for example, setting out on holiday – we assume that it is simply due to the holiday, and fail to draw the lesson that we habitually misuse our powers of attention. The problem is rather like breathing too shallowly until you begin to suffer from oxygen starvation.

Now according to Princeton psychologist Julian Jaynes, all this began to happen fairly recently. In The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (1976), Jaynes offers the evidence of “split-brain research” to argue that the consciousness of modern man has contracted so much that he now lives in only one half of his brain – the left hemisphere (which is devoted to language, logic, and ‘coping’ with everyday life). The right half, he claims (which deals with intuitions, insights and feelings) has become a stranger. And Jaynes suggests that man became a ‘left brainer’ as recently as 1250 BCE.

During the great wars that convulsed the Mediterranean during the second millennium BCE, the old child-like mentality could no longer cope; man had to become more narrow, more obsessive – and at the same time, more brutal and ruthless. (Tension tends to make us cruel.) And in this new state of mind, man lost touch with the gods, and with his own deeper self. About 1230 BCE, the Assyrian tyrant Tukulti-Ninurti had a stone altar built, which shows the king kneeling before the empty throne of the god. But all earlier kings had portrayed themselves sitting beside the god on his throne. Now the god has vanished, and man is ‘on his own’.

It is an interesting theory, and Jaynes argues it very convincingly; but of course, we have no way of knowing whether it is correct. All we can say is that something of the sort must have happened to us at some point during our evolution.

All this raises another interesting point. Since it is the left hemisphere of the brain that deals with calculation, we tend to assume that this is the mathematical hemisphere. But any good mathematician will tell you that mathematics requires the same kind of intuition as poetry or art. This would explain how Oliver Sacks’s subnormal twins could exchange enormous prime numbers. They must have been able to see them, in the same way that Michelangelo could ‘see’ the statue inside a block of marble while it was still in the quarry, or Nikola Tesla could ‘see’ a machine he had not yet even committed to paper. The strange implication would seem to be that, in becoming a ‘left brainer’, modern man actually lost an important part of his rational faculty.

All of which seems to offer interesting glimpses into how our remote ancestors might have possessed ‘high levels of science’ without inventing the concrete mixer.

Everything seems to indicate that high levels of science require intuition rather than reason. Any good scientist would agree. But it also seems to suggest that intuition might be able to create higher levels of science than most scientists would be willing to concede.

Eddie Campbell, the friend who introduced me to the work of Henri Bortoft, offered the following advice:

“Shut the door where you work then sit, bent over your computer keyboard. Put your hands edge-wise on the sides of your head so your line of vision is inside of a tunnel. Stare at the keyboard and let your eyes drift in and out of focus. With a bit of luck you will suddenly find the same sort of ‘shift’ which you get when trying these three-dimensional ‘dazzle pictures’ sold in books. If you are lucky, you’ll suddenly find a strange new version of the familiar keyboard. It satisfies Goethe’s description of active seeing – ‘the perception of an object standing in its own depth’.”

Its aim is the disappearance of normal subject-object perception. Subject and object somehow become one.

Eddie Campbell speculates that “there was a line of transmission from a German school, which used active seeing as a means of scientific discovery, perhaps from the early Middle Ages onwards…. Copernicus ‘saw’ his version of the universe in 1543, some three hundred years before the observational data to support it became available.”

If he is correct, then it might offer us a clue to how ‘high levels of science’ could be possessed by societies that we would regard as primitive.

Excerpted with permission of the publisher from Atlantis and the Kingdom of the Neanderthals: 100,000 Years of Lost History by Colin Wilson (published by Bear & Co, © 2006 Inner Traditions International, www.InnerTraditions.com).

.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.