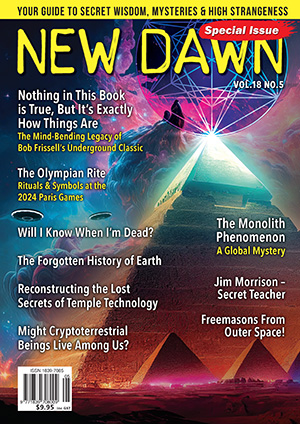

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 18 No 5 (Oct 2024)

In the fall of 2019, I set out to show that American classic rock vocalist Jim Morrison of The Doors is not only a secret teacher but one in the Western esoteric tradition.

A secret teacher is a special kind of person connected to another reality they feel called to explore, a reality beyond what the five senses can perceive and the rational mind can understand. Jim Morrison, Secret Teacher of the Occult: A Journey to the Other Side is about his artistic response to this other reality and why he bravely chose to express it so openly.

The Western esoteric tradition is filled with secret teachers who feel that their strong connection to this other reality demands expression. Morrison travelled this path as a modern shaman through rock music, poetry, and film. However, this path to self-realisation is often problematic as these individuals are frequently misunderstood. They turn inward and embark upon that “stormy search for the self,” the title of an illuminating 1990 work on spiritual awakening by Christina and Stanislav Grof. Morrison found the courage to make us aware of that other reality through poetic lyrics and his shamanic presence.

Morrison’s artistic contributions are manifold. He was one of the pioneering lead vocalists in early rock music history, his most significant influence being the legendary Elvis Presley.

Morrison was drinking one afternoon on the patio of one of his favourite bars in West Hollywood, Barney’s Beanery, when he told American author Jerry Hopkinsthat he wanted to read a biography on Elvis. Hopkins would later co-write with American author Danny Sugarman the first biography on Morrison, 1980’s No One Here Gets Out Alive. Inspired by Morrison’s suggestion, Hopkins wrote Elvis: A Biography, the first of its kind, published in 1971.

Morrison’s 1969 independent film HWY: An American Pastoral gave him a place in film history. Experimental filmmaking was Morrison’s original artistic ambition, leading him to earn a degree in cinematography from UCLA in 1965. Morrison became one of America’s best poets, writing in short verses much like his favourite poet, the late nineteenth-century French boy wonder Arthur Rimbaud, who also influenced the American Beats and singer-songwriters Patti Smith and Bob Dylan.

To appreciate the cosmic consciousness in Morrison’s art and better understand him as a human being, you must look back much further.

Western Esoteric Tradition

Enlightening clues about Morrison’s true self are found in the centuries-old Western esoteric tradition. It’s a thrilling chronicle of mysterious secret teachers who sought to preserve and expand upon what author Gary Lachman calls “rejected knowledge” in his 2015 work The Secret Teachers of the Western World. Lachman tells of the secret teacher’s struggles against what British poet William Blake called “the mind-forg’d manacles” in his long poem The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

The Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle taught Alexander the Great when he was a boy – a historical figure Morrison greatly admired – that all human beings possess a desire to know. The great library established in Alexandria on Ancient Egypt’s Mediterranean coast in the third century BCE – a city named after Alexander the Great – would satisfy the ancient world’s hunger for knowledge for a number of centuries. Some say the Western esoteric tradition was born from this ancient library, a place where Morrison would have felt right at home.

Insatiable Quest for Knowledge

What makes Morrison such a memorable secret teacher is the Alexander the Great warrior-like intensity he channelled into making us aware of that other reality. It’s as if Morrison were picking up where Alexander the Great left off, upset there were no more worlds left to conquer. Only that other reality Aristotle alluded to awaited rediscovery.

Morrison’s desire to know was so powerful he became a warrior for the human soul’s higher aspirations and potential, as many other secret teachers before him such as Hypatia, Giordano Bruno, Jacob Boehme, John Dee, Aleister Crowley, and William Blake. Morrison’s life was like theirs in many aspects, one rich with spiritual awakening, peak experiences, eccentricity, exceptional intelligence, separation from society as an outsider, an insatiable quest for knowledge, timeless achievements, startling convictions, a strong sense of what twentieth-century British author Colin Wilson called “purpose and meaning,” notoriety bordering on pariah status, a chaotic life that sometimes made interpersonal relationships difficult, run-ins with the law, and persecution.

Morrison had a great hunger for knowledge. The rooms he lived in during his high school and university years were stacked floor to ceiling with hundreds of books, his own personal Hellenistic Alexandria-type library.

He made little effort to do well academically yet still earned high grades, focusing on class assignments that interested him and the various books he took inspiration such as Swiss-American artist Kurt Seligmann’s 1948 work The History of Magic.

Morrison made up stories to excuse himself from class and turned down invitations from popular fraternities so he wouldn’t have to conform. What made him tick was an eclectic array of subjects any hip, artistic, spiritually awake person living in the middle of the twentieth century would gravitate to, such as Symbolist poetry, existential philosophy, literature, ancient history, modern art, Freudian psychology, Beat novelists and poets, avant-garde filmmaking, blues music, and occult esoterica such as alchemy, magic, witchcraft, and demonology.

These preferences, combined with his love for Elvis Presley, put Morrison on a preordained path to wake us up to cosmic consciousness rock and roll style, what he referred to in his live performances and poems as the “Universal Mind.”

Morrison was, by temperament, a Romantic. While in high school, he read Colin Wilson’s 1956 work The Outsider, which explores a number of Romantic personalities as well as artists, philosophers and those misunderstood by their contemporaries. Wilson wanted to know why certain geniuses experienced profound “highs” and “lows” that led some to pessimism, depression, drug addiction, terminal illness, and suicide.

Wilson highlights nineteenth-century Dutch post-Impressionist painter Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night as expressing a heightened awareness he dubs “the peak experience.” Wilson notes that Van Gogh committed suicide one year after painting the masterpiece. Before dying, Van Gogh told his brother Theo, “La tristesse durera toujours” (‘The sadness will last forever’). Morrison shared Van Gogh’s bleak view of life, lamenting in his posthumously produced 1978 poetry album An American Prayer, “Could any Hell be more horrible than now, and real?”

Morrison nearly met Van Gogh’s fate on more than one occasion. In Three Hours for Magic, The Jim Morrison Special, Doors guitarist Robby Krieger tells the story of how Doors drummer John Densmore and Krieger once spent an entire night talking Morrison out of killing himself. Krieger remembers having to do this for Morrison more than a few times. Morrison took a walk before sunrise and returned in a completely different mood, feeling euphoric, saying “he’d seen the light” and that he’d written a new song, “People Are Strange,” one of the many classics Morrison would write for The Doors. The person threatening to take his own life a couple of hours earlier had vanished.

Break on Through to the Other Side

Morrison possessed a strong connection to the spirit world. He was adamant that ghosts of dying native American workers he encountered at age three on a road trip with his family in New Mexico had entered his soul. Morrison viewed this spiritual indwelling as the most significant event of his life.

Later, Morrison’s spiritual awakening became intense as his laser-focused reading and journaling invoked numerous peak experiences followed by deep falls into depression, boredom, panic, hopelessness, despair, rage, confusion, and violent thoughts. Morrison’s behaviour would sometimes go beyond eccentric and bizarre into psychopathic, one of the hallmark traits of a shaman. He was looking for help, though he didn’t know where to find it or who to trust, fearful that if he revealed his tumultuous inner life, no one would look at him the same again. While a student at George Washington High School in Alexandria, Virginia, from 1959 to 1961, Morrison expressed having a personal issue he didn’t want to share with his parents or his first girlfriend, Tandy Martin. She insisted Jim talk with a local Presbyterian minister. Reluctantly, Jim agreed. Their conversation remains a mystery.

Morrison would meet another man of the cloth, Pastor Fred L. Stagmeyer, Minister at Large for the Evangelical and Reformed Church. Morrison was friendly to Stagmeyer, who’d made his way backstage one night after a Doors show. Their conversation included a stark warning from Stagmeyer. He pointed out to Morrison that his intent to inspire Doors fans to “break on through to the other side,” to “reinvent all the gods, all the myths of the ages,” and “celebrate symbols from deep elder forests” was not going unnoticed by the Christian Right of 1960s America. Hostility from Christian authorities towards heretics and secret teachers was always the case.

In The Secret Teachers of the Western World, Lachman discusses how the Catholic Church attempted to end the energising influence of the Italian Renaissance’s great awakening when hermetic and occult texts such as the Corpus Hermeticum were translated into Latin. Suddenly, such investigations into the deeper esoteric dimensions of reality were viewed as a form of insanity. A sort of spiritual guerrilla war ensued, with the forming of many secret societies in countries across Europe and in America to preserve “the rejected knowledge.”

For Jim Morrison in the 1960s, the Inquisition had long since passed – prolonged imprisonment, torture, and public executions no longer occurred – but not too much else had changed in religious conservative attitudes to what Lachman calls things “new, alien, and other.”

Criminal Charges & France

Morrison’s penchant for pushing it had already gotten him busted at a Doors performance in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1967, the first performer ever to be arrested onstage. Morrison was later charged by the Miami police with multiple offences, including indecent exposure after the infamous March 1st, 1969, Miami Doors concert where it was alleged he’d exposed himself to the audience. On March 5th, the day Morrison’s arrest warrant was issued, FBI agents in Miami sent a brief report of Morrison’s performance to the office of then-feared FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. This was during Richard Nixon’s presidency, a paranoid man who mounted a campaign to have Beatle John Lennon deported, causing Lennon to cancel a planned 1971 tour of America, known back then as the anti-Nixon tour, with anti-war activists Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin. At the request of former Florida governor Charlie Crist during his tenure between 2007 and 2011, the charges against Morrison were re-examined by the Florida Clemency Board. They were found to be weak, and in December 2010, Morrison was posthumously pardoned.

The 1960s saw the Western world’s first popular occult awakening. Young people wanted to have fun experiencing the unknown and The Doors became one of their most cherished outlets. Morrison’s flamboyant rebellion made him a not-so-“secret teacher.” He was the eldest son of one of America’s most outstanding officers, Rear Admiral George Morrison. “The Commander,” as Morrison referred to his father throughout his childhood, once offered his resignation to the American Navy due to Morrison’s frequent arrests.

One of Morrison’s greatest fears came true one fall day in 1970 as a three-man, three-women jury in Dade Criminal Court found him guilty of indecent exposure. Morrison was sentenced to six months incarceration, possibly in Florida’s notorious Raiford Prison, a hostile place where he knew he could easily be killed.

While still out on bond pending his appeal, Morrison relocated to Paris, France, in 1971 to find himself again as a poet and a person. The pressures he left behind were great. There was the criminal trial in Miami, the fallout from a federal criminal case brought against him in Phoenix, Arizona, for disrupting a commercial airline flight (these two cases put Morrison’s name and face in national news television broadcasts across America), and the expectation that Morrison would remain a highly original artist with The Doors. Besides his enormous legal fees, Morrison was invested heavily in his girlfriend Pamela Courson’s posh West Hollywood clothing boutique, Themis, and her expensive heroin habit, something Morrison detested.

By 1970, Morrison was no longer the lithe and sexy “Lizard King” of The Doors’ earlier years with his growing paunch, and the music scene in Los Angeles wasn’t impressed with his penchant for passing out drunk in public. As his criminal cases made their way through the courts, Morrison did find refuge in his creativity. He left us some real gems. In 1970, his first book of poems was published, The Lords & The New Creatures, a slender volume filled with fascinating and astute insights on cinema, history, voyeurism, art, sexuality, alchemy, shamanism, and American urban life as well as a long poem that recalls the imagery of the surrealist poets and painters Morrison loved. Heproduced and directed, with the help of his UCLA film school friends, the independent film HWY: An American Pastoral, released in 1969,abouta killer hitchhiking through the Mojave Desert who drives into Los Angeles with one of his victim’s cars (Morrison’s 1967 Shelby GT500 was used in the film). Morrison also contributed to creating one of the most widely acclaimed of The Doors’ six albums, L.A. Woman, released in 1971. Despite these successes, Morrison decided he needed a break from America, that it was time to leave Los Angeles for Paris, confiding in Doors manager Bill Siddons that he didn’t know who he was anymore.

Waiting to move into their 4th arrondissement apartment, Morrison and Courson stayed in the same room where 19th-century British author Oscar Wilde had died, impoverished and bedridden, on November 30, 1900. Wilde’s health never recovered after two long years in prison following a conviction on moral grounds. In the weeks after the 1969 concert, a “decency” rally was held at a Miami stadium and attracted over 30,000 people. Would a Florida appellate court overturn the conviction? This unknown left Morrison anxious. Then, just three months after he arrived in Paris, Jim Morrison died there on July 3, 1971. Morrison was laid to rest four days later in the same cemetery as Oscar Wilde, Cimetière du Père Lachaise.

Paul Wyld’s book Jim Morrison, Secret Teacher of the Occult: A Journey to the Other Side explores the mystical and spiritual side of the famed Doors front man. To order your copy, go here.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.