From New Dawn 171 (Nov-Dec 2018)

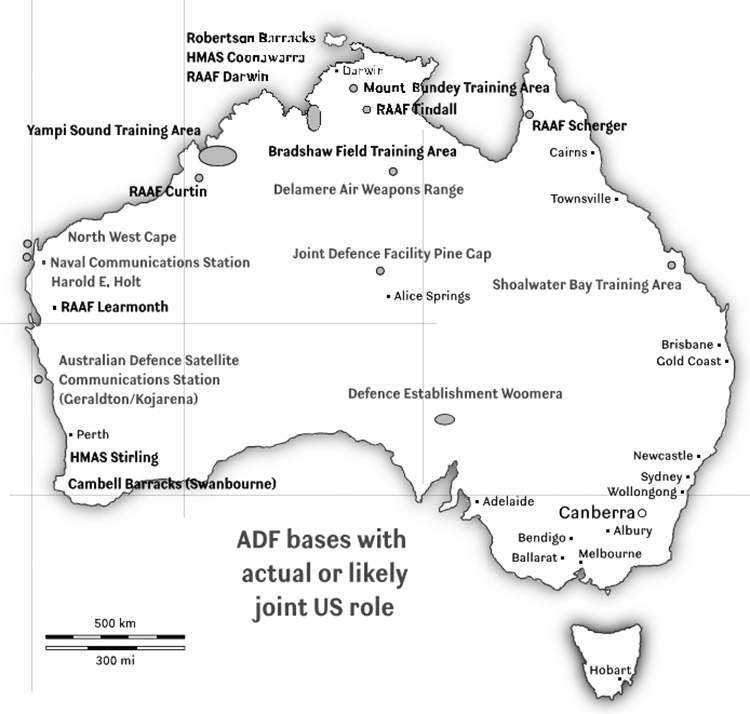

The Joint Defence Facility at Pine Gap near Alice Springs has had a troubling, if discrete history in the Australian political landscape. It is, more than anything, a sign of the pressing inequalities of the Australian-US relationship, a salient reminder of Australia as a distant but valuable satrap to the ever stubborn imperium based in Washington.

“Joint” command is a teasingly deceptive misnomer, given that the facility in the Northern Territory is under US control. What persists is a certain errand boy element fronted by Australian personnel. They supply the territory, the space and the hospitality. The US, boasting its protective umbrella, does the rest.

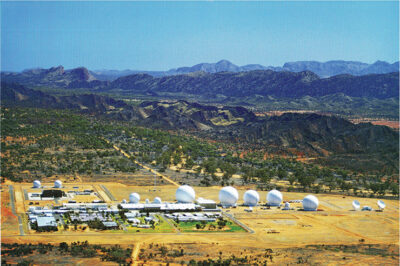

The Pine Gap facility, established in 1970 as one of the world’s largest satellite ground installations, has been responsible for feeding intelligence to American military missions for decades, with, or without the knowledge of the wallahs in Canberra. Over the years, revelations about what the facility is actually being used for have seeped into the media.

The Australian revealed in April 2014 that two Australian citizens – Christopher Havard from Queensland and New Zealand dual national “Muslim bin John” (Darryl Jones) – had been killed in a drone strike in Yemen on 19 November 2013. Both men, supposedly members of the group al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula, were travelling in a convoy of vehicles with Abu Habib al Yemeni, a key AQAP figure. (The Australian did not bother with the term “alleged militants” in describing the fate of the slain.)

Australia’s then Foreign Minister, Julie Bishop, was only informed of the strike after it was revealed that Australian citizens might have been killed. A spokesman claimed that, “There was no Australian involvement in, or prior awareness of, the operation.” It certainly did not concern those at The Australian, who feel that pre-empting guilt by way of execution in an undeclared war without any suitable standard of evidence has “done much to stop the terrorists committing even more atrocities.”

This has not been the view of others. The late Professor Des Ball of the Australian National University, when asked about the strikes in May 2014, reiterated the claims to the same paper that Pine Gap was essentially being used to aid assassination. “I’ve no doubt that intercepts of phone calls and things like that are being intercepted at Pine Gap and used in drone operations.” According to Ball, intercepted signals obtained at Pine Gap were used in a strike against an al-Qa’ida target in Yemen on 3 November 2002. “It was one of the first uses of a drone against targets in Yemen.”

The Australian was a rather late arrival to the party, given that Philip Dorling of Fairfax Media was already reporting that intercepts obtained from Pine Gap were being used in conducting extra-judicial killings in the Middle East. The facility’s “primary function” was to identify radio signals throughout the “eastern hemisphere, from the Middle East across Asia and China, North Korea and the Russian far east.” As one former Pine Gap operator told Fairfax Media: “We track them [the combatants], we combine the signals intelligence with imagery, and once we’ve passed the geolocation intell[igence] on, our job is done. When drones do their job we don’t need to track that target anymore.” Such is the desensitised, amoral world of the signals tracker operating in remote locations.

None of this was new to American investigative journalist Jeremy Scahill, who has been enlightening Australian and New Zealand audiences about the extent of knowledge and complicity in the dirty business of drone strikes. Pine Gap remains the remote sin of Washington’s reach. It also fundamentally inculpates Australia in the same mission, one that extends to its Trans-Tasman neighbour. On 17 May 2014 Scahill told New Zealand’s TV3’s The Nation that he had seen “dozens of top secret documents” provided by US authorities to the NZ government showing effectively “that New Zealand, through signal intercepts, is directly involved with what is effectively an American assassination program.” This barely troubled then New Zealand Prime Minister John Key, who openly suggested that the killings were “legitimate… given that three of the people killed were known al-Qai’da operatives.”

The Purpose of Pine Gap

Robert Cooksey of the Australian National University was one of the first who took an interest in the nature of this “unlisted base” back in 1970. Writing for Dissent, he speculated whether the “weather station” in Alice Springs manned by Detachment 421 of the US Air Force might be powered by nuclear power. The Australian Minister for Supply had been rather oblique about the approval for a US research project at Alice Springs “to conduct long term geological and geophysical studies, including studies of earthquakes and attendant phenomena.” Northern Territory officials simply presumed it to monitor atomic tests, though Cooksey found it curious that this function should be shrouded in secrecy.

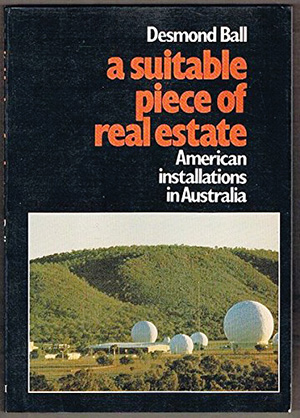

It was Desmond Ball who injected a note of unease in the discussion on the base, noting the multifarious military, scientific, intelligence and space facilities connected with Washington’s interests. “The precise number,” claimed Ball on the facilities, “is difficult to determine – there are problems of official obfuscation and of technical definition – but it is more than twenty.” Along with Richard Tanter, Ball did more work on the subject of drumming up awareness of the secret base’s role on Australian soil than most. A Suitable Piece of Real Estate: American Installations in Australia (1980) drove interest on how Australian territory had become an imperial domain for Washington’s strategic push. His assertion that Australia reclaim sovereignty was deemed “temper democratic, bias Australian.”

The Nautilus Institute for Security and Instability has furthered Ball’s work, keeping a keen eye on the evolution of Pine Gap’s role in security. In an introductory overview on Pine Gap, the Nautilus Institute’s ongoing, updated report on the base notes the following:

“Pine Gap is perhaps the most important United States intelligence facility outside that country, playing a vital role in the collection of a very wide range of signals intelligence, providing early warning ballistic missile launches, targeting of nuclear weapons, providing battlefield intelligence data for United States armed forces operating in Afghanistan and elsewhere (including previously in Iraq), critically supporting United States and Japanese missile defence, supporting arms control verification, and contributing targeting data to United States drone attacks.”

The report pegs Pine Gap’s role to three operational functions, with the original one still being primary: a station for geosynchronous signals intelligence (SIGINT) satellites developed under the auspices of the Central Intelligence Agency. Originally, these were intended to focus on the testing of Soviet missiles. One estimate puts the number of radomes and satellite dishes at Pine Gap at 38.

The second features a function acquired in late 1999 when the base became a Relay Ground Station for detecting missile launches, including Overhead Persistent Infrared (OPIR) which now includes a Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS).

The third is its interception function (foreign satellite/communications satellite), acquired in the first decade of 2000. The Nautilus report notes that two 23-metre dishes appropriate for COMSAT SIGINT Development (Sigdev) were installed within the 30-metre radomes at the end of 1999 and early 2000.

To Peter Cronau of ABC Radio National, the Nautilus Institute’s Richard Tanter was convinced about the ensconced nature of the base in the plans of US security:

“Pine Gap literally hardwires us into the activities of the American military… So whether or not the Australian government thinks that an attack on North Korea is either justified, or a wise and sensible move, we will be part of that… We’ll be culpable in the terms of the consequences.”

Other sources have added to the jigsaw. David Rosenberg, a US employee at the base, supplied a valuable portrait of the functions of the base in 2011. In 1990, Matthew Denholm subjected the strategic base argument to broader discussion.

All this cut and dried material conveys the relevance of Australia’s continued geographical role as a dry goods merchant for Washington, its haberdasher of the Pacific. Not only does it supply the data required for drone strikes, it also served as a useful tool in directing US air operations over Vietnam and Cambodia. This troubled Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in the 1970s, who became a subject of deep distrust in Washington with his threat not to continue the lease connected with the base. This supplied an ample pretext for a flurry of communications between Washington and the opposition leader, Malcolm Fraser, who became the celebrated usurper in the fall of the Whitlam government in 1975.

Australia remains America’s glorified dogsbody and, in any future war, a conspicuous target. Enormous latitude is permitted for US personnel at Pine Gap.

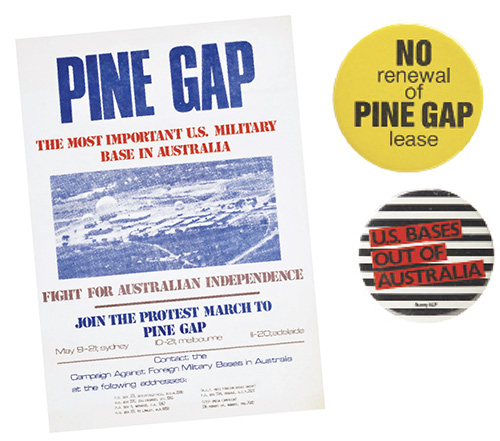

Prosecution & Protest

In 1952, when the Defence (Special Undertakings) Bill became law, it did so without opposition. There was, however, one note of warning from an otherwise unquestioning Dr Herbert Evatt of the Australian Labor Party. For one thing, the danger of legislative overreach was apparent: “the bill contains very important provisions which extend beyond that particular subject. They may be open to some criticism on analysis but, after consideration, the Opposition believes that the bill should be passed.”

Protests and prosecutions have followed. A strong streak of feminist and female activism against the base has characterised dissent and an attempt to breach the veil of secrecy. On 11 November 1983, a Boston Tea Party style gathering was held on the green lawns on the Base. 111 women were arrested for trespass, all giving their name as Karen Silkwood, a renowned anti-nuclear protester. Some 700 women gathered, being described by the Alice Spring News as “Karen Silkwoods.” Support, albeit indirectly, was also offered by twelve female parliamentarians from the Labor Party, including Senator Susan Ryan, then Minister for Education.

At various stages, prosecutions on charges of trespass under the Defence (Special Undertakings) Act 1952 have also been mounted, though the prosecution effort in 2007 against protestors was laughed out of court by the presiding judge, Daynor Trigg, who deemed the statute “a bit of nonsense.” The defendants were duly acquitted by the Northern Territory Criminal Appeals Court, who quashed attempts by prosecutors to seek a retrial.

As late as last year [2017], six self-proclaimed “peace pilgrims” received the attention of authorities for sporting musical instruments and pictures depicting war casualties onto the base. The prosecution of Margaret Pestorius, Paul Christie, Jim Dowling, Franz Dowling, Andy Paine and Tim Webb centred on their entering of the clandestine base in September 2016 had been obstinate and typical.

The grounds advanced by Michael McHugh SC for the government made weak reference to the history of peaceful protest that had marked the practice of Australian democracy. He even drew a curious precedent from the archives about how the Suffragettes had, in their day, shown the way on civil disobedience. They, it should be noted, were deemed to have acted illegally, though ultimately successfully, in their cause. The defence argued that the Commonwealth Criminal Code legitimised their protest because it was necessary to prevent a loss of life. As Pine Gap supplied targeting information for drone strikes, its disruption would purportedly save lives.

Justice John Reeves found no merit in the argument of extraordinary emergency, but nor did he prove entirely cooperative to the prosecutors. On 4 December 2017, the court refused to impose prison sentences, despite the guilty jury verdict. “I do not accept the Crown’s submission,” said the judge dismissively, “that your offences potentially struck at the heart of national security.” All six were fined for unlawful entry to the tune of $1,250 to $5,000, and Paine was found guilty of the additional charge of carrying a photographic device on the base.

During the course of trial, testimony was elicited by various figures which formed the public record. Former Greens Senator Scott Ludlam spoke with conviction from the stand. “There are moral and ethical questions,” he charged; “there are also deep legal questions about the authorities relied upon by the United States Government to undertake drone assassinations in at least six countries that I am aware.” Ludlam’s points are sound in their logic: complicity expands rather than contracts, and Australian funding and hosting of the base invariably places risks to Australian citizens from the perspective of drone strikes, and, in another sense, the vantage point of future prosecutions for crimes against humanity.

A Blot on Sovereignty

Australia, for Ball, seemed gripped by a near infantile fear about its security, a requirement almost Freudian in its search for a protective paternal power. “There is a residual fear in Australia that we can’t defend this huge territory and only the Americans can really save us. We always have been a fearful country. We’ve always needed great and powerful friends.”

In a tone similar to the late Malcolm Fraser with his resentment of Australia’s “Star Spangled manner” (despite being an initial enthusiast of US power, Fraser did change his tune), Ball felt that the base over time exemplified the worst in the US-Australian alliance. As he told the ABC in 2014, he had reached a point where he could “no longer stand up and provide the verbal, conceptual justification for the facility that I was able to do in the past.”

The joint US-Australian facility functions in a defiant administrative limbo, one resistant to Australian sovereignty, despite its proclaimed collaborative status. It remains hostile to the inquiries of Australian citizens on what role the base plays. Pine Gap has had a singularly corrosive effect on Australian public life. It has whittled away rights of protest and entrenched secrecy. It has attacked basic civil liberties, with US authorities co-opting Australian personnel to do the work of the US military. With each provocation by daring protesters, with each exposure of the ludicrousness of secrecy surrounding the base, crumbs are filling the gaps, data filling the files.

“Since our action,” claimed Paine, “more evidence has emerged detailing the role of Pine Gap in extrajudicial assassinations, in nuclear weapons targeting and in illegal mass surveillance.” The most troubling aspect of this is whether Australia’s general citizenry cares.

Footnotes

1. www.theaustralian.com.au/opinion/editorials/heavy-price-of-jihad-hits-home/story-e6frg71x-1226887014723

2. www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/policy/pine-gap-supports-us-drone-hits/story-e6frg8yo-1226923350422#

3. www.smh.com.au/national/pine-gap-drives-us-drone-kills-20130720-2qbsa.html

4. www.smh.com.au/national/pine-gap-drives-us-drone-kills-20130720-2qbsa.html

5. www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/breakfast/dirty-wars—the-world-is-a-battleground/5472612

6. www.wsws.org/en/articles/2014/05/24/dron-m24.html

7. Bruce Juddery, “Hint of Work at Pine Gap,” The Canberra Times, Sep 17, 1970, 14.

8. Desmond Ball, A Suitable Piece of Real Estate, 19.

9. nautilus.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/The-_Joint-Facilities_-

revisited-1000-8-December-2012-2.pdf

10. nautilus.org/publications/books/australian-forces-abroad/defence-facilities/pine-gap/pine-gap-intro/

11. www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-20/leaked-documents-reveal-pine-gaps-crucial-role-in-us-drone-war/8815472

12. David Rosenberg, Inside Pine Gap: The Spy Who Came in From the Desert Hardie Grant Books, 2011.

13. Matthew, Denholm, “The advantages and disadvantages of allowing United States military/strategic bases to be maintained in Australia,” Cabbages and Kings 18 (1990): 45-71.

14. Women For Survival, founded during the Pine Gap Women’s Peace Camp in 1983. For more, see the record: trove.nla.gov.au/people/1477462 and www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/PR00097b.htm. See also Melbourne University Archives (Victorian Women’s Liberation and Lesbian Feminist Archive) and James Cook University Library (Trewern Collection). See Women for Survival, Pine Gap camp – 11 November 1983 (Haymarket, NSW, 1983).

15. Noted by Bryan Law, “Entering the ‘gap’ between what’s right and what’s legal’,” Webdiary, Oct 17, 2005 and noted in Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, “Pine Gap protests- historical,” nautilus.org/publications/books/australian-forces-abroad/defence-facilities/pine-gap/pine-gap-protests/protests-hist/

16. closepinegap.org/media/

17. www.smh.com.au/national/des-ball-the-man-who-saved-the-world-20121220-2bpdd.html

18. www.abc.net.au/7.30/content/2014/s4066678.htm

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.