From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 10 No 4 (Aug 2016)

Biochemist, author, spiritual teacher, kayaking fisherman, founder of an intentional community, misanthrope – Robert de Ropp was a complex man. Within him, the scientist, the magician, the missionary, the domestic oaf, hermit and warrior jostled for position. Practical and forthright, and distrustful of wide-eyed spirituality, he nevertheless became widely known to seekers in the 1960s. Books like Drugs and the Mind, The Master Game, Warrior’s Way and Self-Completion helped many to bridge the gap between drug experiences and disciplined spirituality.

Born in England in 1913, he came from an aristocratic background, but the early death of his mother in the post-WWI influenza epidemic and the subsequent lack of interest shown by his father resulted in a bizarre childhood.

His father was a Lithuanian Baron who in the 1920s lost most of his money in ill-advised financial ventures. At the age of 12, de Ropp, who had until that point been advancing through the elite English school system, found himself dumped for two years at the family seat in Lithuania. The mansion itself had not been maintained and, having been shelled in the war, was close to a ruin. Robert rattled around in a freezing cold, rat-infested great house that could accommodate fifty people. The neglected estate was run by the peasant families who had been there for generations, if not centuries. In place of his Oxbridge-oriented classical education the half-starving de Ropp found himself receiving a practical schooling in fishing and traditional agriculture from the old retainers.

With little warning he found himself extricated by his father only to be resettled once again, this time in the Australian outback, where he found himself working in a hopelessly misjudged farming venture. When this went bottoms up he made his way to Port Adelaide where he tried unsuccessfully to drown himself. Somehow, the fourteen-year-old managed to get back to England by himself with ten shillings in his pocket. Via a family connection he was taken in by the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, whose pastoral pieces are now a mainstay of popular classic music radio programming. Finally achieving some stability, Robert studied science and became a molecular biologist.

Robert would only have occasional contact with his father, who lived until 1973. William de Ropp was a fascinating figure in his own right. A Germanic Lithuanian aristocrat, he became a confidante of Hitler and enjoyed close contact with him in the mid-1930s. William de Ropp had close connections with high-ranking British figures who were in favour of appeasing Hitler. He was actually being employed as a double agent who was able to obtain considerable intelligence for the British on Hitler’s ambitions and the state of the Luftwaffe.

Encountering Ouspensky & Gurdjieff

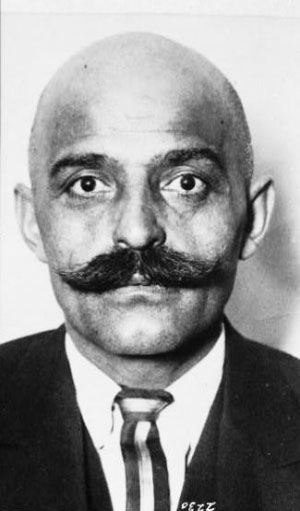

In the 1930s Robert de Ropp got to know the novelist Aldous Huxley and his friend Gerald Heard who taught meditation. Heard was one of the first westerners to teach eastern meditation styles but de Ropp found his approach over-emotional. Not so P.D. Ouspensky, who seemed free from sentimentality and pretentiousness. After a hesitant start, de Ropp joined Ouspensky’s groups and began the work (based in the teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff), which, with development and adaptation, would dominate his inner spiritual life.

De Ropp was tough and well-prepared for the physical exertions that form part of the Gurdjieff work. G.I. Gurdjieff taught that man (humans) has no single indivisible ‘I’. Desires, thoughts, feelings, urges, pass constantly through us, each of them claiming the title of ‘I’ temporarily. Certain typical clusters of these ‘I’s form somewhat separate personalities. Each personality may have a separate set of concerns that collect together, representing the different aspects of one’s concerns or the separate contexts in which one must relate to other human beings. As an example, many adolescents experience a taste of this when they experience the discomfort of recognising that the way they behave with family may be very much at odds with the way they behave with friends.

De Ropp found this to be a key to self-understanding. Obviously disposed to coming up with new categories, as we shall see in other areas of his writing, he analysed his own constituent personalities. What was unique in de Ropp’s approach was his use of the personalities in autobiography. Throughout Warrior’s Way – incidentally one of the most readable, honest, and varied of spiritual autobiographies – de Ropp characterises his behaviour according to the personality which was dominant. These included archetypes such as the Magician, who was able to feel the mystique of nature, and the Scientist, always applying rationality and looking for evidence. Yet others are more individual. The Missionary was that part of de Ropp who wanted to convert others to what he saw as the truth of the Gurdjieff-Ouspensky system. The Missionary was energetic and sincere but authoritarian, dogmatic and domineering. Opposed to the Missionary was the Domestic Oaf, desirous of family, children, a steady job, of house and land. (At times his personalities included the Recluse, the Cynic and others; this was a pragmatic rather than a systematic approach.)

De Ropp worked every weekend at Lyne Place in England and then, after the end of the war, at Franklin Farms in New Jersey for over a decade. He was not alone in feeling that Ouspensky had lost his way and succumbed to a form of the guru trap, with a drinking problem and surrounded by followers who had become dogmatic and authoritarian. He was also not alone in feeling that in his last months Ouspensky had shrugged off this role and lived like a spiritual warrior at the end.

After Ouspensky died de Ropp finally met Gurdjieff in New York in 1948. With some exceptions, the strict firewalls that Ouspensky erected against what he thought was the increasingly erratic influence of Gurdjieff had broken down. Long term students of Ouspensky encountered Gurdjieff in a series of vivid and pungent encounters. Gurdjieff struck de Ropp as a king in exile, perhaps the last Magus. He was the most impressive man de Ropp met in his entire life – a view to which he held 30 years later. Gurdjieff combined the Tarot archetypes of Magician, Hierophant, Emperor and Hanged Man. Yet, when Robert and his wife walked back with Gurdjieff after a movements class in New York, he wracked his brains trying to remember the question he should have asked Gurdjieff, but it just would not come and they continued in silence. Soon afterwards Gurdjieff would be in such demand that there was no chance for direct contact; De Ropp would have a long illness, and the master died the next year in 1949. In retrospect, de Ropp decided that although Gurdjieff represented unparalleled spiritual possibilities, he just wasn’t up to the challenge. “For the intelligent and the strong he [Gurdjieff] could provide the inspiration of a lifetime. But for the stupid and the weak he could be dangerous, even deadly. You have to be a pretty strong player to be able to play games with such a master.”1

The Domestic Oaf won out, eager for a job, a mate and a family, but life was not to be easy. Now on his second marriage and second family, de Ropp built himself a house from scratch for $3,500, and held down a good scientific post.

Both de Ropp’s wives suffered from mental illness, his first wife to such an extent that she was institutionalised for decades. His scientific professional life would now intersect with his inner mental life to understand the influence of drugs on the mind.

Drugs & the Mind

De Ropp had a common sense attitude to drug use. He didn’t believe that psychoactive substances, whether modern pharmaceuticals or traditional plants, could lead one to anything like true awakening. Yet neither did he agree with the increasingly vociferous prohibition in response to the 1960s drug scene. Anyone who wished to experiment with drugs should be able to do so, preferably in a safe situation. Even though de Ropp had experimented with drug use and concluded that it was a “blind alley, a cul de sac, a dead end,”2 he still recommended that others should not take him for his word but try their own experiments – preferably in safe conditions. Legislation against psychedelics and other mind-altering drugs, he believed, “strikes at one of the most fundamental of all liberties, the liberty of the individual to explore his own inner world by means of his own choosing.”3

His book Drugs and the Mind not only addressed issues such as the nature of addiction and the use of drugs to treat mental illness. Already in 1957 de Ropp had written: “The greatest public health problem at the present time is mental illness.”4 The book had entire chapters devoted to peyote and marijuana. Of the many mind-altering substances de Ropp personally experimented with, it was not the more dramatic and powerful hallucinogens like LSD or peyote that impressed him, but cannabis when taken as an extract in a sizeable dose.

Among the love and peace generation, de Ropp became, if not quite a household name, then certainly the author of one of the significant books of the period. Drugs and the Mind kept company on hippy bookshelves with Huxley’s The Doors of Perception and works by Timothy Leary and Alan Watts. The disciplined and scientific Englishman, now in his fifties, found himself fêted by young Americans who were tuning in, turning on, and dropping out. De Ropp was one of a small number of older people who could see the potential of the new movement. Leary’s message was turn on, tune in and drop out. But could these explorers of inner space turn up (on time), tune up their bodies, and drop unnecessary attachments?

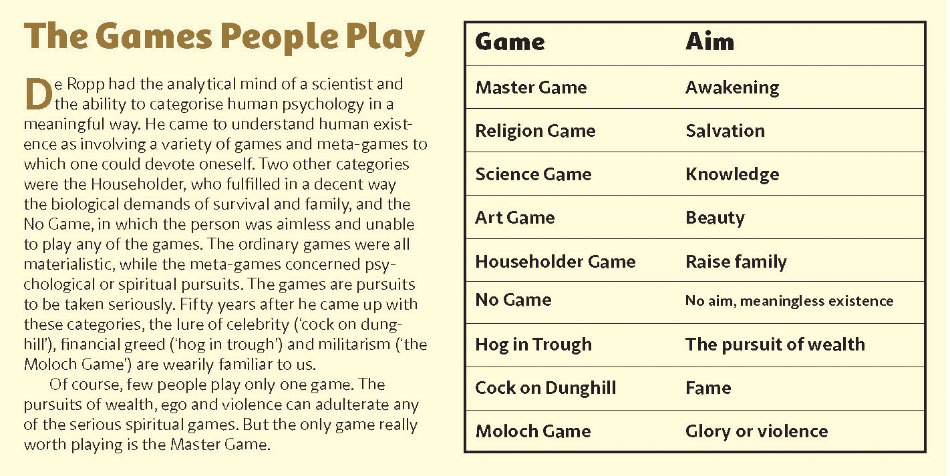

Unlike Leary or Watts, each of whom de Ropp felt had succumbed to the temptations inherent in being a guru, de Ropp managed to navigate the rapids of the psychedelic tide. Although he could see that young people were in desperate need of self-discipline and grounding, he also felt that the Fourth Way of the Gurdjieff-Ouspensky teachings was somewhat authoritarian in its approach, and neither entirely successful in its methods or transmission. This line of thinking led to his next major book, released in 1968, The Master Game: Beyond the Drug Experience, which sold in the hundreds of thousands.

Spiritual Explorers & Teachers

Throughout his life de Ropp encountered many spiritual explorers and teachers. By the time he moved to California in 1962 he had developed a knack of testing would-be teachers. It was not an infallible touchstone of soundness yet it worked well enough. He simply challenged them in his forthright manner. When he did this to Timothy Leary in 1962, after a long and inspiring talk from Leary on his plans to establish a utopian psychedelic community on the Pacific coast of Mexico, Leary simply turned off his hearing aid. It was a quirky response from Leary but didn’t bode well for the future of a co-operative enterprise. As is so often the case with spiritual teachers, the message was – my way or the highway. De Ropp saw Leary’s hallucinatory tropical utopia as impractical, and he was right – it was closed down by the police after just a few weeks.

Of the flower power generation, de Ropp admired Ken Kesey but felt he hadn’t followed through successfully. Only Steve Gaskin, founder of the Farm community, met with his approval.

De Ropp may be accounted a teacher himself. How did he fare? He describes his hesitancy and self-questioning, but many teachers feel thus inwardly. Rather than displaying these to the pupil, spiritual teachers often overcompensate for their internal doubts.

Despite his love for describing life as a game, de Ropp certainly had something of the puritan about him. He detested alcohol and tobacco. City life was not for him and only country living seemed authentic. But most of us live in cities and towns, and they aren’t without their advantages.

De Ropp could see that the situation of humanity in the West was changing rapidly and he was able to negotiate the rapids produced by the flood of change. He began his own experimental community, the Church of the Earth, in Sonoma County, California. It was never intended to be a large group. A good portion of the group, with de Ropp’s blessing, started going to J.G. Bennett’s more ambitious International Academy for Continuous Education at Sherborne, England. De Ropp had reservations about those who came back from the accelerated ‘evolution’ of Sherborne House, dubbed by one wag the ‘Bennetron’. “I had expected well-trained, obedient, ready-for-service disciples,” de Ropp wrote, “I received rebellious, starry-eyed, self-opinionated ‘adepts’.”

When they returned they were in no mood for serious teachers, or so de Ropp concluded, and the whole enterprise collapsed. The Church of the Earth was intended to have been built around the three pillars of garden, temple, and university, feeding the body, spirit and mind respectively. In a 1974 book of the same name, de Ropp describes their attempts at working together and setting up a rural community. The garden seems to have fared the best. The temple or dojo never seems to have got far beyond a wonky physical structure, and of the university there was little mention at all apart from a vague notion of seminars. Perhaps the project’s collapse was to de Ropp’s advantage after all. As a result he never was seduced by the guru trap.

Warrior’s Way & Self-Completion

De Ropp seems to have been most stimulated by his attempts to harvest the garden of the sea. He designed and built his own kayaks and became a skilled fisherman. He found the sea a demanding teacher, unforgiving of lapses of attention, requiring the fisherman to successfully adapt to the rhythms of nature. At the end of his penultimate book, Warrior’s Way, de Ropp contemplates existence from his tiny boat in the Pacific Ocean on the northern Californian coast. He has somehow made contact with a Taoist spirit teacher named Fong, who has given him the gift of balance between yin and yang, receptiveness and relaxation balancing the austere demands of the Gurdjieff work; he was a Taoist hermit going with the flow. De Ropp seeks no ultimate answers, feels no need for any metaphysical belief, has no desire or faith in a survival of the personal ego. “My spirit will dance there as the shadow of that rock, among seagulls and pelicans, sea lions and starfish. I would like to give my flesh back to the ocean to feed the fish whose bodies have so often fed me.”5

Forty years ago de Ropp’s concern for the state of humanity and the planet was part of the emerging green movement. His view of modern westerners as “a spoiled, careless, pampered, town-bred manswarm” might seem harsh but we are already several stages down the road, oblivious of the warning signs. We do not even notice them as we wander towards oblivion, our sight focused on smartphones as we stagger towards the cliff. (This is metaphor but it seems that every week someone walks into a lamppost or off a cliff because they’re absorbed by their smartphones. There should be a word for the phenomenon.)

In his final book, Self-Completion, in which he introduces himself as an elderly hermit, he included insights into Gnosticism and the latest developments in science. The Gurdjieff-Ouspensky work still provided the spine of his teaching but his pragmatic approach combined the work with aspects of Taoism, psychology, Sufism, Arthur Koestler’s holons, and his own bluff, no-nonsense assessment of western culture.

In 1987, at the age of 74, he died while kayaking in his beloved Pacific. Having pitted himself against the ocean for years, one suspects he knew that he could not win every time, and would have been content to have died in that manner, honourably, alone with nature, in the Warrior’s Way.

Footnotes

1. Warrior’s Way, Dell Publishing, 1979, 192

2. The Master Game: Beyond the Drug Experience, Delacorte Press, 1968, 23

3. Ibid.

4. Drugs and the Mind, Evergreen, 1957, 167

5. Warrior’s Way, 351

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.